Religion tends to be different from a mere philosophy of life in its claim to offer a way through, out of, or beyond what presently holds us back or stands in the way of our highest fulfillment. In the genuine traditions of spirituality, such a solution avoids the temptation of either an other-worldly escape on the one hand, or on the other a do-it-yourself program where individuals must struggle to make it on their own. It’s not only a perspective on reality that religion provides, then, but a way of salvation – a path in life that leads to and promotes the freedom, happiness, connection and wholeness we seek as human beings.

Religion tends to be different from a mere philosophy of life in its claim to offer a way through, out of, or beyond what presently holds us back or stands in the way of our highest fulfillment. In the genuine traditions of spirituality, such a solution avoids the temptation of either an other-worldly escape on the one hand, or on the other a do-it-yourself program where individuals must struggle to make it on their own. It’s not only a perspective on reality that religion provides, then, but a way of salvation – a path in life that leads to and promotes the freedom, happiness, connection and wholeness we seek as human beings.

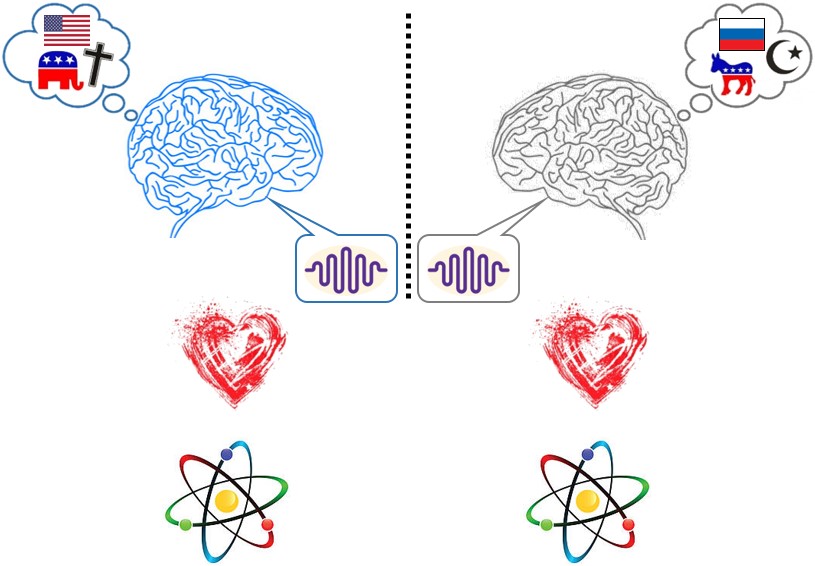

Our tendency today is to regard the various religions as spiritual retail outlets, each putting its program on offer in competition for the consumer loyalty of shoppers – in recent decades called seekers or the unchurched. As we should expect, each name-brand religion has terms and conditions that are unique to its history and worldview. In addition to its characterization of what we need to get “through, out of, or beyond,” each religion has its own individualized set of symbols, key figures, sources of authority, and moral codes that members are expected to honor.

Muhammad and the Quran are not featured in Christianity, and neither are the teachings of Jesus or Christian atonement theories studied in Buddhist temples. The halacha and mitzvah of Moses are not among the devotional aspirations of a Native American vision quest, nor is zazen practiced in Islam. When we view the religions according to what makes them unique and different from each other, the way of salvation seems like it must be one choice among many.

In face of such confusion, perhaps secular atheism has it right: Do away with religion altogether and the world will be a better place for us all.

If you care to study religion more deeply, however, you will understand that it (in all its healthy varieties) is a sociohistorical expression of something much more profound. Here the terminological distinction between religion and spirituality is helpful, so long as we can resist setting these against each other, as when religion becomes “organized religion” and spirituality gets relegated to one’s individual quest for inner peace or mystical insight.

Religion and spirituality go together – and always have – in the same way as the vital life of a tree goes with the material structure of its roots, trunk, branches and leaves. Our own inner life is always (and only) inner to an outer mortal body. These are not two things that can be separated, but two aspects of one reality distinguished in a fuller understanding.

The questionable doctrine of the immortal soul notwithstanding, this dynamic unity of two aspects (inner essence and outer expression) cannot be divided. Not only do “inner” and “outer” imply each other logically (i.e., in thought), they are inseparably united ontologically (i.e., in being) as well.

It’s not as if the inner life of a tree can exist outside and without the support of its physical system. Nor can the inner life of soul persist absent the body; it is inner only to a whole self, not as one part that can be separated from another part. In the same way, religion without spirituality is dead, but spirituality cannot exist without embodiment in religion. Religion comprises the symbols, stories, beliefs, rituals, and practices that embody the spirituality of individuals in community. Such expressions or outer forms can be highly relevant and effective in what they do, serving to channel the essence or inner life of spirituality into our shared experience.

But these forms can also fall out of alignment and lose relevance, as when the model of reality (cosmology) serving as backdrop to early Christian myths shifted by virtue of scientific discovery from a three-story fixed structure to an outwardly expanding universe. This cosmological shift gradually rendered the sacred stories – of angels descending, a savior ascending, the Holy Spirit descending, the savior descending again, and the company of true believers ascending at last to be with god forever in heaven – literally nonsense. Or at least nonsense if taken literally.

Unfortunately, when religion is sliding into irrelevance, believers, at the admonition of their leaders, can start to insist on the literal reading of sacred stories. If the savior did not literally (that is, factually) go up to heaven and will not literally come back down to earth, and very soon, what becomes of these stories, the canon of scripture, and to the entire tradition of faith? Since a “true story” must be based in fact, and facts are properties of physical reality, then these stories must be literally true or not at all. When this error in narrative interpretation finds a footing in religion, the whole enterprise starts to close in on itself and the lifeline to a deeper spirituality is lost.

If we were to open the religions again to the wellspring of spirituality we would witness a renaissance of creativity, meaning, and joy across the human family. The culturally unique elements would be appreciated as eloquent “styles” in the expression of our inner life as a species, flourishing in fertile niches of geography, history, tradition, and community.

The metaphorical narratives of mythology is where spirituality first breaks the surface into cultural expression. By looking through these narrative expressions, deeper into the unique and culture-specific elements, we can discern what I will call the “Shining Way” of salvation. Again, I’m not using this term salvation as a program of world-escape but instead as a guiding path towards our fulfillment and well-being as individuals, communities, and earthlings. As I’ve tried to unpack the finer details in many other posts of this blog, here we will only take in the big picture and broad strokes of this Shining Way.

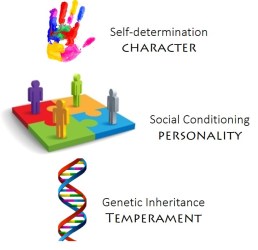

We begin life in a state of unconscious oneness, where our individual consciousness is yet undifferentiated from the provident environments of mother’s womb and the family circle. This is the state depicted in myth as a garden paradise, where every requirement of life is spontaneously satisfied and reality is fully sufficient to our needs. Consciousness is completely anchored in the synchronicity of the body’s urgencies and the enveloping rhythms of providence. We call this our ‘first nature’ since it is what ushers us into the animal realm of instinct, survival, and the life-force.

It was out of this unconscious oneness that our individual identity gradually emerged and gained form. What we call our ‘second nature’ consists of the habits – the routines of behavior, feeling, and belief – that our tribe used to shape us into a well-behaved and obedient member of the group. This is a period of growing self-consciousness, of sometimes painful experiences of separation from the earlier state of immersion where we felt enveloped and secure.

In mythology it is that fateful transition away from oneness and into a separate center of personal identity known as ‘the fall’. Paradoxically it is at once both a loss and a gain, a fall out of unconscious oneness and an exciting entrée to a self-conscious existence.

As our second nature, ego ideally develops increasing strength, particularly through the formative years of childhood. Again ideally, we will arrive at a point where our personality is stable (based in a calm and coherent nervous state), balanced (emotionally centered), and unified (managed under an executive sense of who we are) – the key indicators of ego strength.

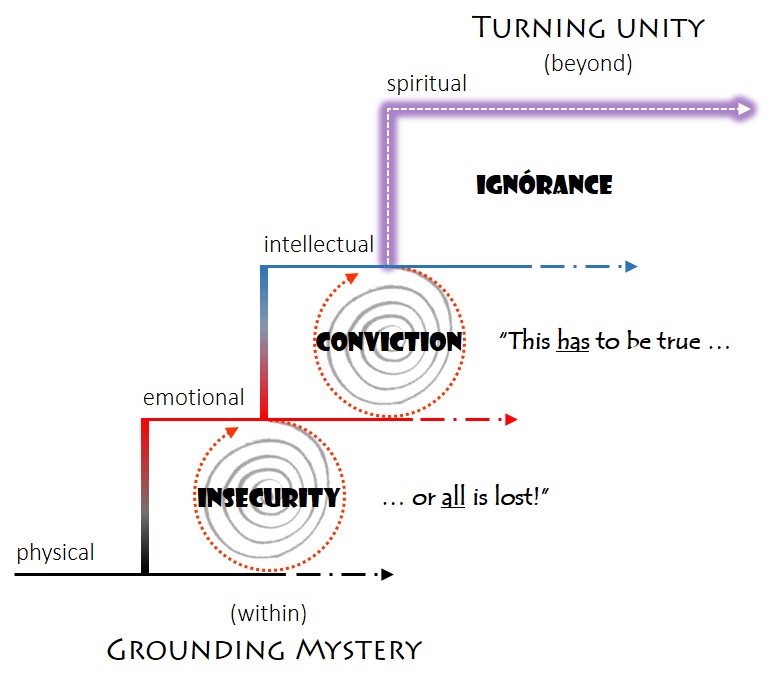

I have to insert that ominous qualifier ‘ideally’ because ego consciousness doesn’t always advance in the direction of our creative authority as individuals. If our mother’s womb and early family circle were not all that provident – subjecting us to dangerous toxins, stress hormones, abuse or neglect – and because we inevitably make some poor choices of our own, ego can get stuck in a closing spiral of neurotic self-obsession.

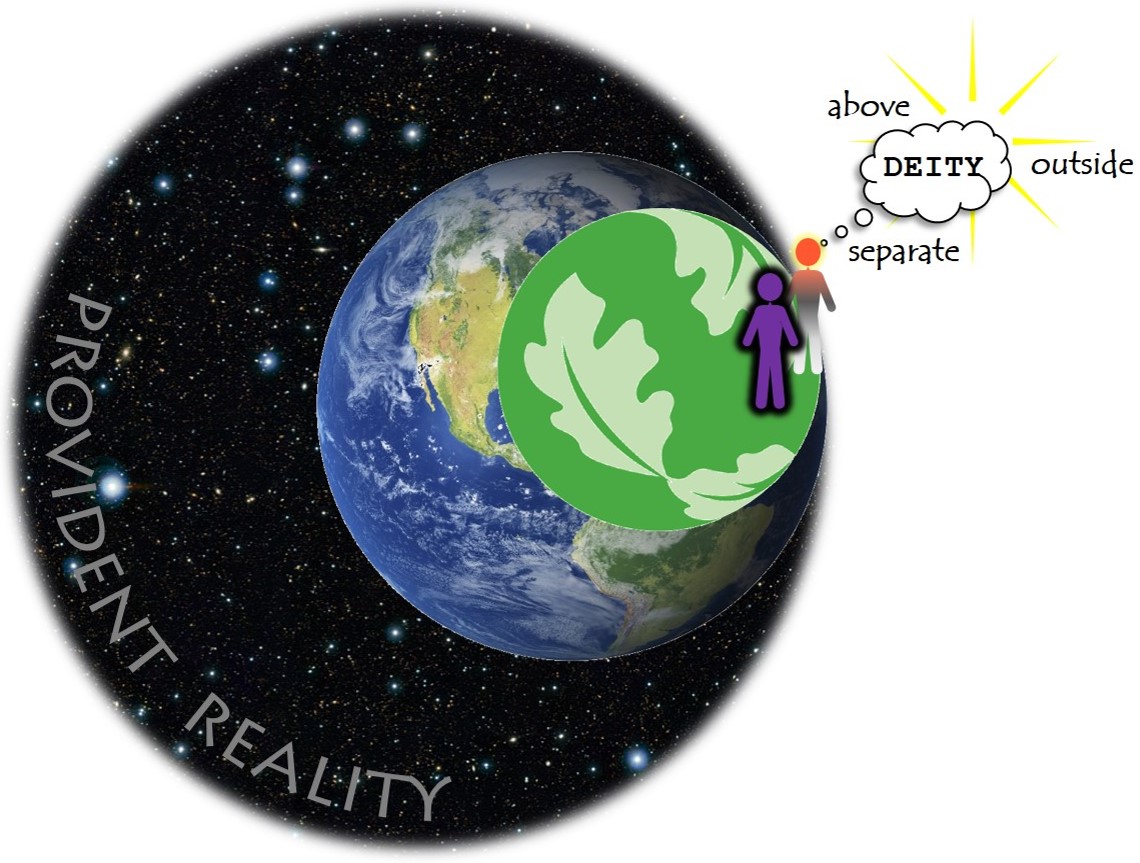

As I have explored in other posts, theism is a form of religion that features the super-ego of a patron deity who authorizes a tribe’s moral code and serves as its literary model in the character development of devotees. Theism is a necessary stage in the evolution of religion, just as ego formation is a necessary stage in human development. But just as ego needs to eventually open up to a larger transpersonal mode of consciousness (we’ll get to that in a bit), a healthy theism must also unfold into a larger post-theistic perspective.

Ego and patron deity co-evolve, that is to say, and when ego formation goes awry, theism becomes pathological. Now you have a social system that is both a projection of ego neurosis and a magnifier of it throughout the collective of like-minded believers.

A neurotic ego is deeply insecure, defensive around that insecurity, conceited (“It’s all about me”), and unable to think outside the box of belief (i.e., dogmatic). Not surprisingly, these traits find their counterpart in the portrait of god among pathological forms of theism. Ironically, while these forms of theism tend to glorify separation, aggression, and violence in their concepts of god, on the Shining Way of salvation these are seen as the source of our greatest suffering.

But let’s get back to the good news.

When ego strength has been achieved in our second nature, we are able to surrender our center of identity for a larger and fuller experience of life. In Christian mythology, this release of the personal center is represented in the scene where Jesus surrenders his will to a higher calling and commits his life on the cross into the hands of a compassionate and forgiving god.

NOTE: I’m keeping the action in the present tense because the myth is not primarily an account of the past, but rather an archetypal representation of the Shining Way. As archetype, Jesus in early Christian mythology is not merely a historical individual of long ago, but represents humanity as a whole. He is, as the apostle Paul recognized, the Second Adam or New Man, the turning point into a new age.

When we surrender our center of personal identity, consciousness can expand beyond the small horizon of “me and mine.” What we come to is not a larger sense of ourselves but, as Siddhartha observed, an awareness of ‘no-self’, an experience of consciousness dropping the illusion of separation and ego’s supposed reality. What the neurotic ego would certainly regard and strenuously resist as catastrophic oblivion is experienced instead as boundless presence.

Such insight marks the breakthrough to unity consciousness and is represented in myth as the Buddha’s earth-shaking affirmation under the Bodhi tree, and as the resurrection of Christ from the dead.

According to the Shining Way, liberation from the habits and conditions of our second nature leads us by transcendence to our higher nature. We have progressed in our adventure, then, from a primordial unconscious oneness, through the ordeals and complications of self-consciousness, and with the successful release of attachments we come at last to the conscious wholeness of body and soul, self and other, human and nature.

If we’re going to work this out, we will have to do it together. There is no other way.