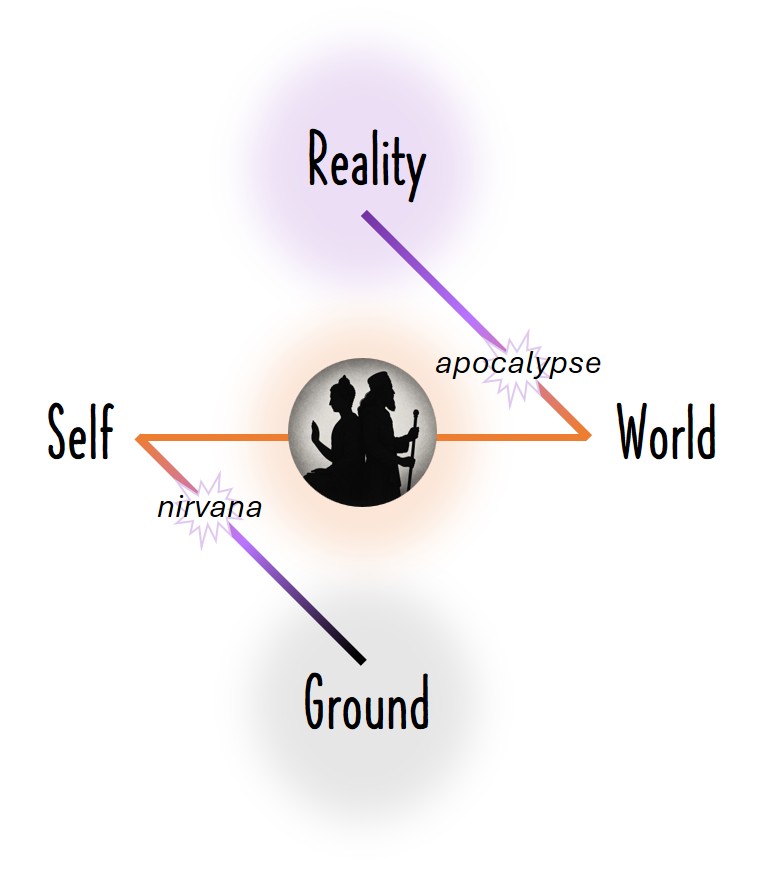

One theory of meditation sees it as a portal to peak experience and enlightenment, providing access to transcendental dimensions of being and consciousness.

People spend decades perfecting the mindset and techniques that facilitate these breakthroughs, dedicating great amounts of time to the discipline of meditation.

Another theory sees meditation as a conditioning routine for meeting the challenges of daily life and the longer project of becoming a more liberated, self-aware human being in the world.

It’s not about gaining transcendental access to other dimensions as much as learning how to cultivate wellbeing in this one.

It may sound as if I’m setting up an either-or debate between these two general theories of meditation – one as rising above and episodically escaping the traps and doldrums of ordinary life, and the other living more intentionally in the stream of everyday events.

As is the case with everything else that our mind splits and sets in opposition by its binary logic, the truth is probably a paradoxical (both-and) insight, farther upstream and somewhere in the middle.

Even at that, however, my personal preference is more for the second than the first.

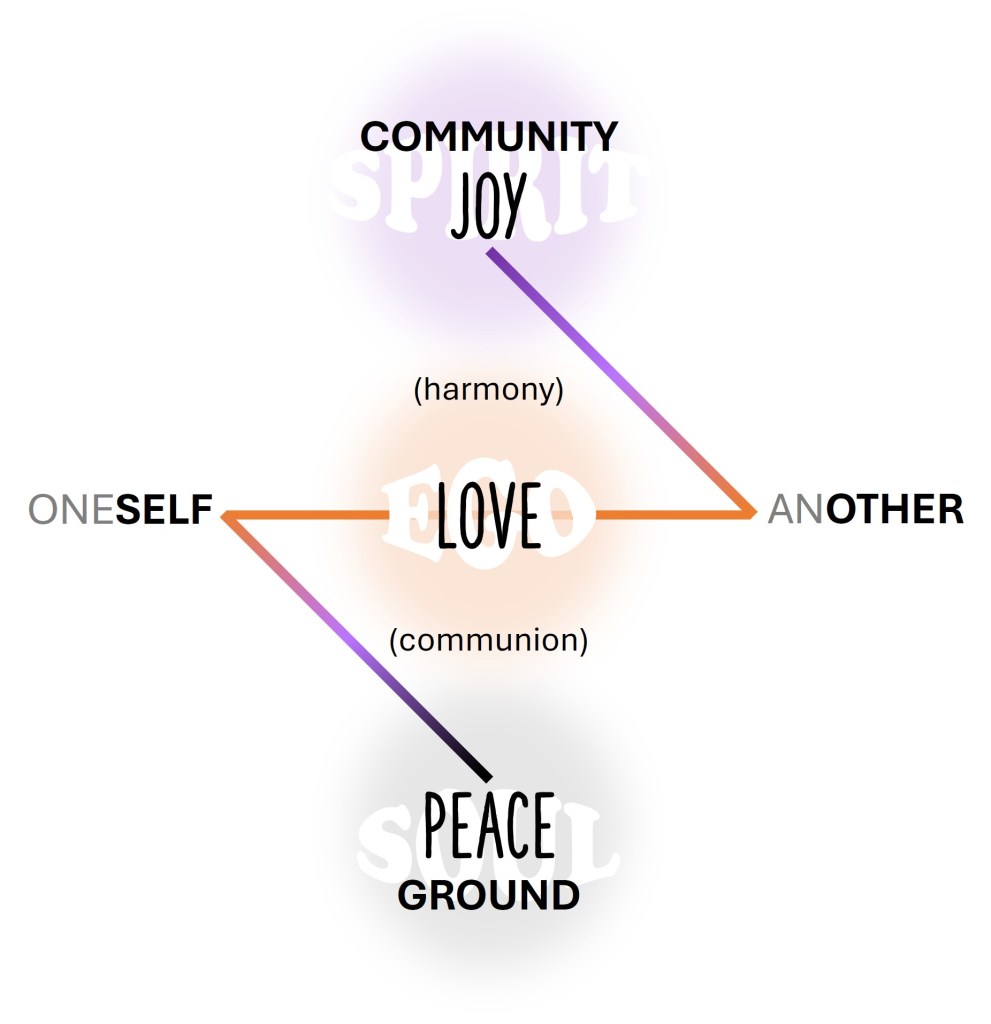

What we’re dealing with in any case is the Human Spirit – human psychology, the psychodynamics of consciousness, or what I will name in this post “spiritual power.”

I don’t mean by this term some metaphysical entity which is alien to our body and will some day continue on without it, like a transmigrating soul from another realm, skipping from one lifetime to the next on its way home.

Rising from the depths of our human biology, emerging through and reaching beyond our personal ego, the Human Spirit is the mystery of our existence circulating in us like breath (Latin spiritus), grounding us in Being, connecting us to the greater web of Life, waking us to our true potential.

Insofar as these two theories of meditation play out a dichotomy of values, we should further point out that while the first might regard one’s community life as structured around our exercises in solitude, the second acknowledges community life as the crucial work zone where meditation has its greatest salutary effect.

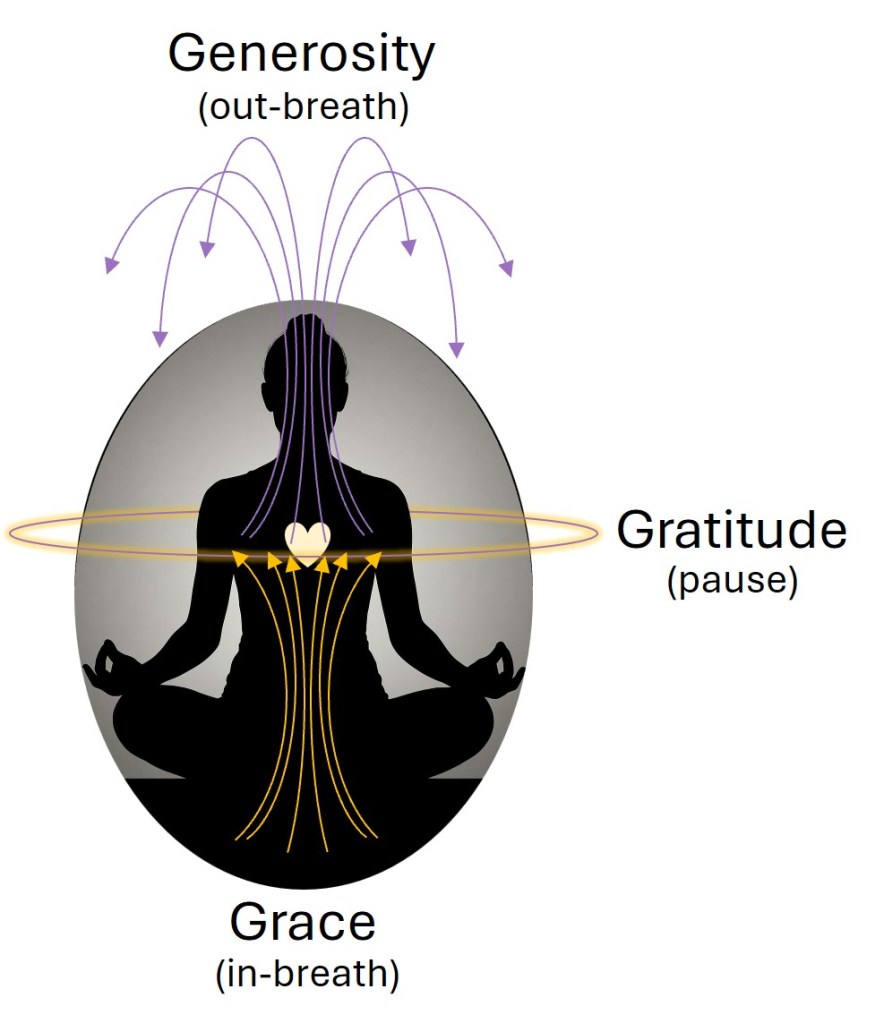

I offer the illustration above as a guide in our exploration of spiritual power – this mystery of the Human Spirit, filling and flowing through each of us. A meditator is sitting in the “lotus position” at the center, whether in the focused effort of breaking through to a higher dimension or building a centered strength for the challenges of everyday life, is left for my reader to decide.

Using the full cycle of rhythmic breathing as our template, we will explore the three stages of spiritual power: (breathing in) Grace, (holding the breath) Gratitude, and (breathing out) Generosity.

Rather than considering these stages of spiritual power from a position of objective detachment, I will invite you to recall a situation, recent or farther back, when you felt stressed and triggered by things happening to you or around you – a time when a familiar neurotic style snapped into play and threatened to take you over. Or maybe it did take over and you found yourself in that familiar spiral of anxiety, frustration, exhaustion and regret.

Such moments can be frequent during the course of ordinary experience, which is where I have argued the real salutary effect of meditation is demonstrated.

Does our practice help us, by making it more likely that we can respond rather than merely react to triggering conditions and events? Regardless of the ease with which we might detach and take flight to other dimensions of being and consciousness, the distractions and annoyances (i.e., the “triggers”) of everyday life call on our ability to respond – on our response-ability.

With that situation fresh in your memory, and recalling the fast-moving sequence of stimulus-reaction-fallout, find your center and take in a full breath. Notice the difference in your nervous state and how you feel now from how you felt then. As the first stage of spiritual power, Grace involves centering and grounding yourself in the Now.

You are no longer a mere reactor, but have established yourself in the position of creator – as one with the capacity, equanimity, intention, and freedom to act.

What would Grace have looked and felt like in that situational replay?

Across the religions and world cultures, Grace is universally associated with authority, majesty, and divinity. Beyond being a synonym for elegance and dignity, however, Grace is acknowledged and revered as the individual’s (human or god) self-possession, of their being anchored inwardly to an infinite power supply. Their actions are not compulsive reactions to circumstances, but arise from deep within themselves as creative initiatives and freely chosen (intentional) responses.

Having drawn that breath from the Ground of your inner depths, now pause and hold it softly for several seconds. The second stage of spiritual power, Gratitude, invites you to consider a different way of regarding this situation – not in hostile or defensive reaction, but instead welcoming and receiving it as a guest into your presence. What opportunity is here? What discovery or revelation awaits? What lesson is offered? What is being made possible through your intention to be open and inviting to what is here now – to whatever comes?

In some cases, it may simply be a feeling of Gratitude for another opportunity to learn patience, to practice forgiveness, or take a different perspective.

Maybe you are just grateful to be here, to be alive and given another chance to show up and do the right or better thing, this time around.

Upon reflection, holding Gratitude for this moment and what it brings, spiritual power can now breathe out in Generosity. One part of Generosity is releasing or letting go, for nothing can be given if you are not willing to release it. By now, however, there is no holding back. You are grounded in Grace and filled with Gratitude, surrendering fully to the outflow of Generosity.

Had you been in this centered and resourceful state for the situation you are now recalling to mind, how might you have responded?

Spiritual power is generative, restorative, or transformative, depending on the situation. Transformation necessarily includes a phase where the existing form or arrangement is broken or dissolved in preparation for the emergence of New Being (cf. Paul Tillich). In breathing out, you direct your creative intention into fostering conditions and contributing to the process of communal (i.e., mutual, transpersonal, organizational, planetary) harmony and wellbeing.

The impact of your Generosity is likely to provoke various reactions from others involved, some of whom may be deeply invested in (or “attached to”) keeping things the way they are. The consequence in such cases may well be resistance and blowback, which will tempt you to modulate or restrain your Generosity so as not to upset expectations and the status quo.

The Human Spirit has no stock in the status quo, however, but seeks instead greater freedom, authenticity, health, wholeness and joy.

Breathing in (Grace) draws spiritual power from the Ground within you. Holding the breath (Gratitude) provides the opportunity to reflect and reframe your perspective on what this moment offers. Breathing out (Generosity) is your devoted practice to cultivating favorable conditions and giving of yourself for the salvation – i.e., the healing, wholeness, liberation and fulfillment – of all sentient beings.

Meditation is the portal to peak experience and enlightenment, enabling you to serve as a clear channel of spiritual power into the challenges and opportunities of everyday life.

Go get ready for the next time. We all need you to practice.