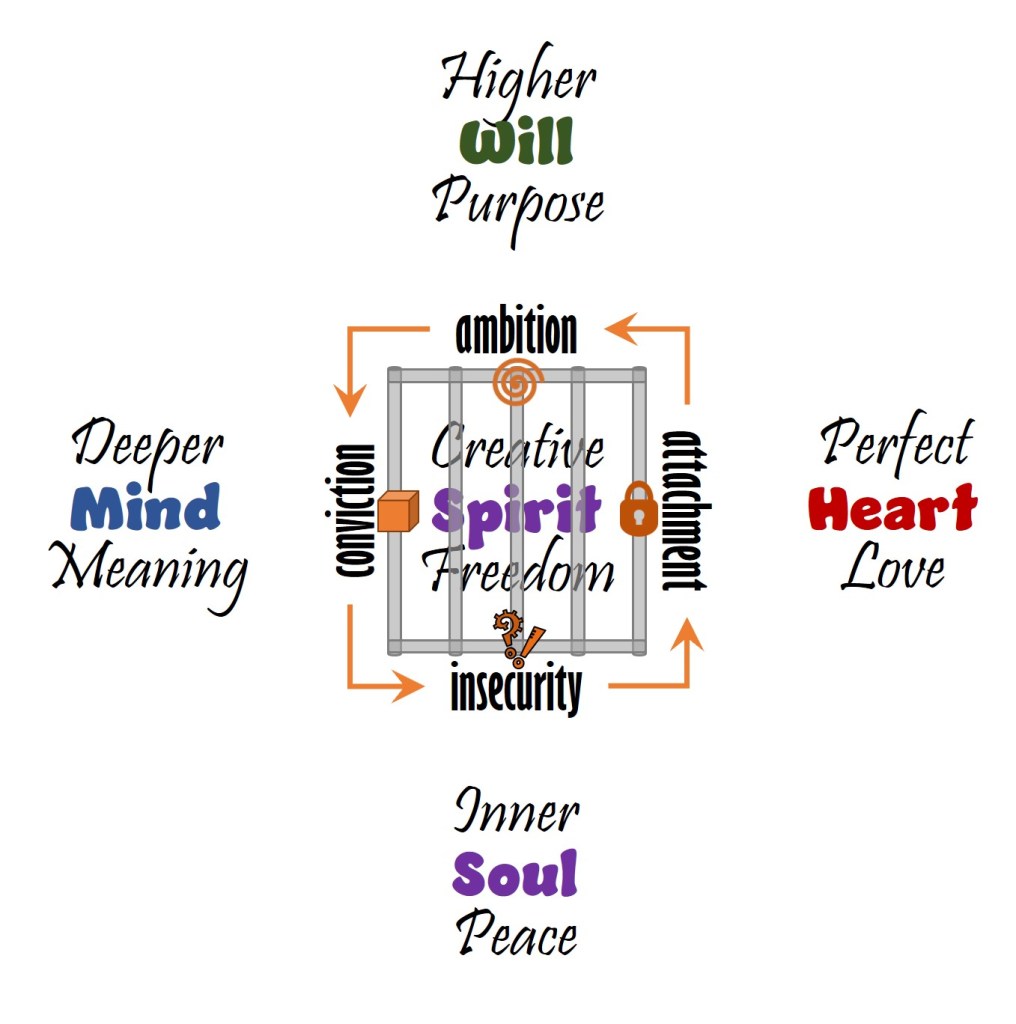

The Human Spirit in us needs freedom, and what it seeks or aspires to is inner peace, perfect love, higher purpose, and deeper meaning. Think of the Human Spirit as a wildly creative force of genius that empowers our awakening, liberation, and fulfillment as a human being – to become fully human and fully alive.

For a tragic majority of us, the Human Spirit is like a beautiful and powerful wild tiger locked inside a cage. Without freedom, it cannot be creative. All it can do is pace inside its cage, back and forth and around in circles, drained of its fierce energy and now only a vestige of its essential nature: frustrated, exhausted, and depressed.

The true longing of the Human Spirit is for a life of inner peace, perfect love, higher purpose and deeper meaning – not to languish here in this hell.

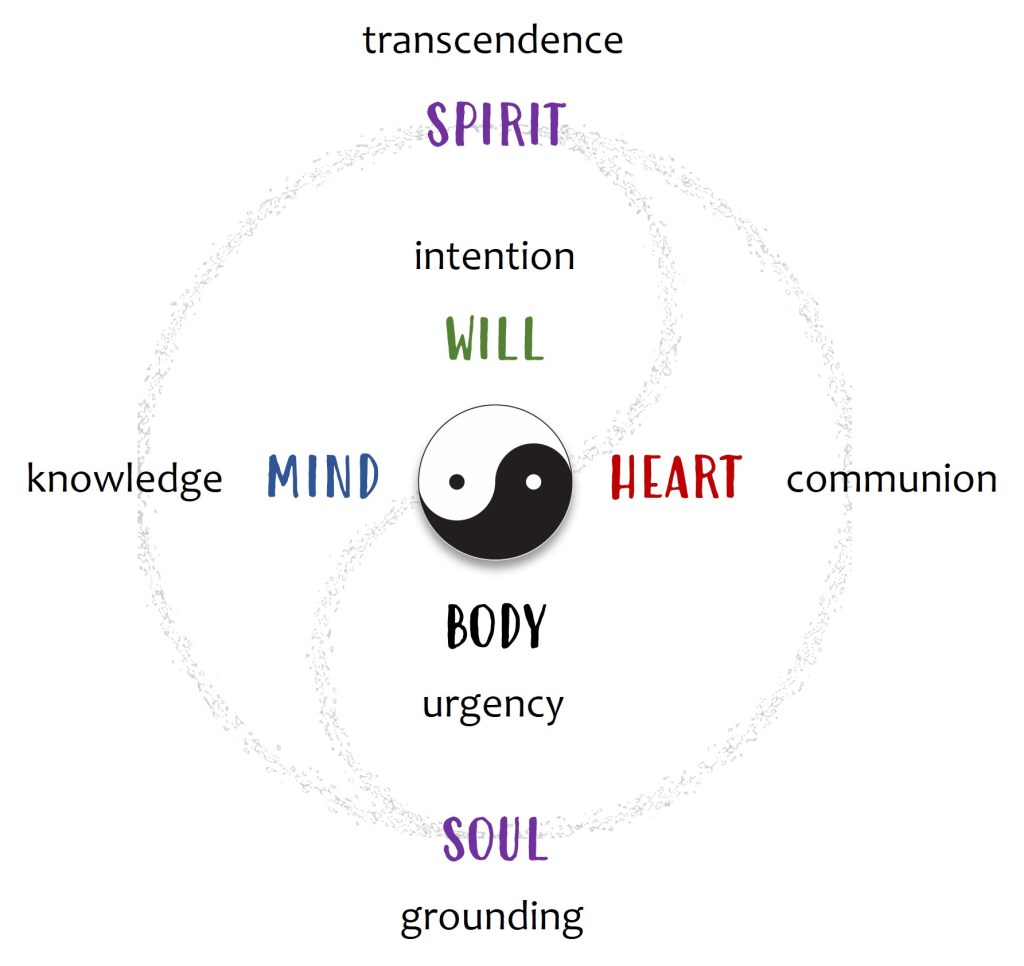

Those four aspirations – for peace, love, purpose and meaning – are aligned with the four types of intelligence, or threads of consciousness, in a human being; what I name our quadratic intelligence.

- Our spiritual intelligence (SQ) is centered in the Soul and seeks or aspires to inner peace.

- Our emotional intelligence (EQ) is centered in the Heart and seeks or aspires to perfect love.

- Our volitional intelligence (VQ) is centered in the Will and seeks or aspires to higher purpose.

- Our rational intelligence (RQ) is centered in the Mind and seeks or aspires to deeper meaning.

This braid of threads is unique to humans, as far as we know, and each thread in the braid is integral to human consciousness. These don’t operate on their own but rather form a complementary system, with each thread of consciousness and center of intelligence contributing its own frequency to the whole.

The generator at the core of this system, energizing the distinct pathways of its complex circuit, is the Human Spirit.

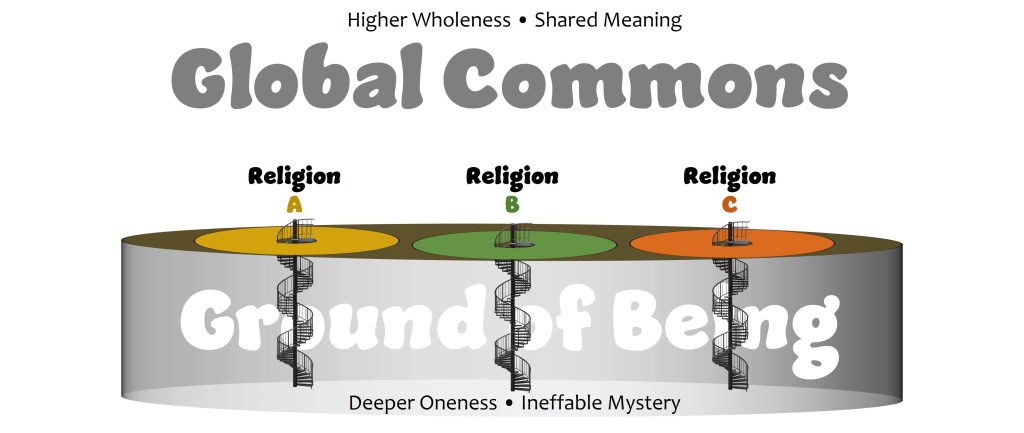

In this blog, I have been developing the framework of a New Humanism – not one that regards “Man as the measure of all things,” that chooses secular values over sacred ones, or argues for our need to break from religion and be done with mythology. Instead, it honors the human being as storyteller, meaning-maker, and world creator, who is (all of us) on the journey to becoming fully human and fully alive.

Categories of the supernatural, metaphysical, esoteric, and otherworldly are used very sparingly, if at all, so as to avoid their unnecessary distraction from the proper focus of our meditation. Even god can be a distraction if we take it literally and start looking for it (or deny its existence) in the objective world.

The New Humanism is not atheistic but post-theistic, concerned with the evolutionary project of human progress, awakening, liberation, and fulfillment.

What we are naming the Human Spirit, then, is nothing more – and certainly not less – than the lifeforce and adventure of consciousness in ourselves as human manifestations of Being.

Every living thing arrives, develops, matures and actualizes its nature along a trajectory with an aim toward what the organism is intended to be – what we might call its species ideal. Humans have an evolutionary inner aim as well, what the philosopher Aristotle called an entelechy.

Early life events, the provident or less favorable conditions of its environment, along with genetic vulnerabilities and the accidents of dysfunction, disease, and random casualty, can foreshorten an organism’s normal lifespan and thereby interfere with its fulfillment.

For human beings, the provident or less favorable conditions of our early environment are especially critical in determining whether and to what extent the Human Spirit in us can flow to the intelligence centers of Soul, Heart, Will and Mind.

When the Human Spirit is locked in a cage, our aspirations for inner peace, perfect love, higher purpose, and deeper meaning are frustrated, resulting in the exhaustion and depression that are so prevalent today. The lifeforce and creative energy that would otherwise activate and empower our progress toward fulfillment, is instead trapped inside a psychic structure built by our ego for its domestication.

Paradoxically ego’s refuge is Spirit’s prison, and it soon becomes our personal hell.

Here’s how we do it.

Each of the four walls of our cage is made of neuropsychic “material” that fuses with the other walls to make an enclosure where we feel safe, loved, capable and worthy – the four subjective (or feeling-) needs of ego. The very process of ego formation entails a siphoning and sequestering of the Human Spirit into a separate self-conscious personal identity, a separation that brings with it a certain inevitable degree of insecurity.

It’s the depth and severity of this inevitable insecurity that determines how rigid and small our cage needs to be. To the insecure ego, a smaller space feels safer.

Already in our infancy, we begin attaching ourselves to objects, people, and specific conditions that can help calm our anxiety and connect us, in their own ways, to a Reality from which our own emerging ego is in the process of separating us. The reflex reaction of our insecurity, then, is to form attachments, each charged with the inarticulate expectation that it should make us feel safe and more secure.

The Human Spirit is blocked (i.e., locked in a cage) by our attachments, preventing its creative freedom from activating our Heart’s aspiration for perfect love.

To the insecure ego, attachment is love; the wisdom teachings, however, are very direct in calling out this equation as delusional. Notwithstanding their available counsel, we eventually discover from our own experience that neurotic attachment leads to codependency, entanglement, and the terminal foreclosure of healthy relationships.

Neurotic attachment is compelled by two opposing drives: a desire to feel safe, loved, capable and worthy; and a fear that our demand won’t be met, that it won’t work out or be enough, or that the goal of our pursuit will elude us. This dual-drive of desire and fear is the inner dynamic of ambition (ambi = two or both), and its spiritually damaging effect is illustrated in our metaphor of the tiger (the Human Spirit) pacing in circles inside its cage.

These pacing circles, however, are really a psychodynamic spiral where the fear drive in ambition injects increasing degrees of desperation into the desire drive, making our efforts more frantic and our expectations even more unrealistic. Exhaustion and depression are the predictable outcome of turning compulsively, and hopelessly, in circles.

This downward, drain-circling dynamic in ambition is the antithesis of higher purpose, which is the true aspiration of our Will.

One more wall and the tiger cage is complete. As the spiral of ambition tightens and our attachments consistently let us down, the unresolved insecurity deep in our body and soul forces the Mind to form convictions (symbolized in the diagram by a block or box) that keep us from having to face Reality.

As the word implies, conviction makes the Mind a “convict” to its own beliefs, which we defend as absolute truths beyond question, doubt, or debate. This becomes the final – and for the Human Spirit, fatal – factor in separating our anxious ego from Reality.

Here, with us nervously clutching our attachments, chasing down the drain of ambition, and our convictions walling-out the Present Mystery of Reality, ego finds meager relief and a momentary refuge – but not for long.

In the meantime, the Human Spirit paces and turns inside this cage we’ve made, waiting for us to wake up from our delusion.

Hopefully, it won’t be much longer.