Metaphors operate at a level where experience first breaks over the threshold into expression, the real presence of mystery into representations of meaning. At a very deep level – just short of the very deepest – human beings orient themselves according to a guiding metaphor of life itself.

What is life, and what is your place in it?

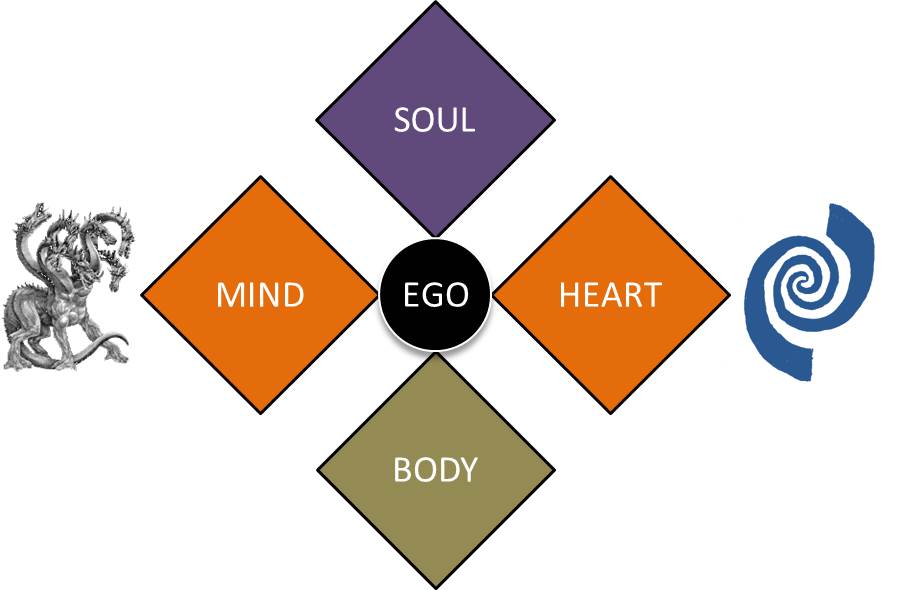

Western culture is organized around a guiding metaphor of life that we could name circling the drain. With its accent on the individual, everything tends to be oriented according to the individual’s perspective, more specifically to the perspective of that separate identity called ego.

This is who I am. This is my tribe. These are the things that belong to me. Such are the ambitions I have for myself. I have a limited amount of time to realize my dreams, and finite resources to exploit before my time is done.

I do my best to hold and protect my own, to get what I need and have enough of what I want, but it’s very apparent that life is leaking away from me all the while.

This drain metaphor of life spawns other secondary metaphors, which are more enmeshed in language and hence more meaning-full. The farther out and dependent our minds become on this web of meaning, the more dogmatic we get in our beliefs, the more convicted of our certainties, and the more vulnerable we become to anxiety and depression. We worry over many things, sink into fatigue and discouragement, and get just enough rest to rush out and try it again.

Western religion has compensated for this inherent bipolarity in egoism with its invention of an afterlife fantasy where the ego will live on forever once the body expires. Physically my body is trickling down the drain with each passing minute, but I (ego) will not die. Instead I will pop out on the other side, fully intact and without the drag of a mortal frame. Over there, I will be reunited with my loved ones who went down the drain before me, and I will be everlastingly happy.

The metaphor of circling the drain, therefore, is what inspired our familiar and highly defended notion of salvation as a rescue project. What we’re looking for cannot be here, for the obvious reason that everything is going down the drain. Our only hope is to find the way out – out of this world, out of our bodies. Not really out of time, exactly, since heaven is supposed to be everlasting, but at least in time without a drain to worry about.

Outside of religion, the metaphor of life as circling the drain has stimulated a view of the individual as consumer – needing, demanding, taking, devouring, using, spending, wasting and casting aside the leftover junk. We have been brainwashed to regard ourselves as chronically empty – of what exactly, no one knows for sure. But there are countless fillers on display in the marketplace that we are encouraged to try out. Keep your credit card handy.

So we oblige by filling ourselves up with all manner of “stuff” and in the process have become discontent and possessive, malnourished and overweight, popular and lonely, renting storage and buying insurance policies to keep it all safe as we inwardly waste away.

There is another metaphor of life, one that predates our Western notion of the drain by thousands of years. Its roots are in the organic intelligence of the body – the very problem from which the ego seeks escape. It is central to a grounded and mystical spirituality. Instead of circling the drain, this metaphor invites you to join the stream.

Life is a flowing river, and you are part of the mystery. There’s no need to throw yourself into a tightening spiral of anxiety, craving, attachment, frustration, disappointment, desperation and depression.

Life is a flowing river, and you are part of the mystery. There’s no need to throw yourself into a tightening spiral of anxiety, craving, attachment, frustration, disappointment, desperation and depression.

True enough, since the larger culture has been constructed around the drain metaphor, you will be tempted to regard this idea as something else you need to take and make your own. But that’s just ego again.

By its nature, a stream cannot be possessed. If you should try to dam it up and turn it into a reservoir, you might achieve the illusion of ownership and control, but your entire perspective will have shifted to a vertical axis centered on leakage and loss prevention – the drain again.

Joining the stream promotes a very different outlook on reality, a different way of orienting oneself in the world. As a metaphor, it counteracts the ego’s tendency towards nervous consumption and the grip-down on me and mine. Rather than closing focus down into a spiraling anxiety around the drain hole of mortality, the stream metaphor opens our focus up to the larger reality to which we belong.

Our separation from reality and antagonism to life is only a delusion of ego consciousness. I (ego) am not really separate from everything else, but my insecurities and defenses make it seem so. And yet, this mistaken sense of separateness is what alienates me from my body and hence also from life itself.

The metaphor of life as a stream is also a gentle reminder that it’s not about me. Admittedly it can be a considerable – perhaps even traumatic – change in perspective that’s required, and one that isn’t supported by the general culture we live in. To some extent this has always been the case.

Even though their teachings were later turned into programs of escape from mortality and its complications, Siddhartha and Jesus were really speaking about the opportunity afforded in each moment of life to release the neurotic compulsions of “me” and “mine” for the sake of a larger and more participative experience. The Buddhist “no-self” (anatta) and the Christian “new mind” (metanoia) are early concepts that get at this idea of joining the stream.

The above chart sets in contrast these two different images, identifying the points where each guiding metaphor works its way into our worldview, our fundamental attitudes toward life and the values we uphold, as well as our approach to the mysteries of death and dying.

Everything changes as you learn to give in to the greater reality, rather than stubbornly insist that reality deliver on your demands. You are wonderfully free of convictions and the need to be right. You begin to understand that nothing belongs to you, that there is only One Thing going on here and you are part of it.

In life and death, you can be fully present and trust the process. This is the essence of faith.