Over the years I have come across authors who decry hope as an unnecessary setup for human unhappiness. They fault it for pulling the focus of concern away from present reality and projecting it into a fantasy of the future that never quite arrives as expected. Perhaps because so much creative energy has been invested by humans in unproductive wishful thinking, which presumably includes religious pining after Paradise, these well-meaning critics of hope suggest that we’d all be better off without its distractions and disappointments.

I get their point, in one sense. Hope is a setup of sort, and what human beings hope for rarely “comes true.” And yes, hope can siphon precious energy away from the challenges of real life, sometimes even persuading us to let opportunities pass or even trash what’s real for something better later, on the other side. Because baseless, unrealistic, and otherworldly hope has been used as an accelerant of violence (in the name of future hopes) as well as a justification for emotional detachment from the pressing issues of contemporary life, the solution is to discredit it in the hope that we will live more fully, and more responsibly, in the present.

But as I have a sympathetic affection for our inherently conflicted species, I’m going to take a different slant on this matter of hope. Seeing as how depression is the malady of our modern age, could it be that living without hope – or, following the sage advice of these authors, forsaking hope in the interest of a more reality-oriented mindset – is at the root of our problem? Maybe we shouldn’t confuse hope with mere wishful thinking, with longing for something away from, different than, or after the challenge presently upon us.

As animal organisms, humans are anchored by physical needs to the living earth. When these basic needs are met – assuming that our pursuit of them hasn’t gotten tangled up in the complications of emotional insecurity (which is a generous and entirely unrealistic assumption, I know) – the satisfaction we feel is a key ingredient in the happiness we seek. Happiness is more than the satisfaction of our needs, but I’m ready to say that it isn’t possible unless our survival and health are supported in some adequate degree.

Perhaps it was to seduce us into satisfying our basic needs, that nature sprinkled the fairy dust of pleasure on the things we require to live, reproduce, and flourish as a species. This, I will say, is the second key ingredient to happiness. We don’t need pleasure to live, but the pursuit of it tends to get us involved in doing what is necessary for life to continue. If apples weren’t sweet to the taste, if sex didn’t bring convulsions of ecstasy, or if reading a good book was utterly devoid of pleasure, there’s a decent chance we wouldn’t bother with them.

If satisfaction is mostly about our physical and developmental needs, then pleasure might be the evolutionary bridge from an existence oriented on survival to one that’s virtually preoccupied with enjoyment. The pursuit of pleasure is probably at work in our tendency as sensual-emotional beings to be both gluttonous consumers (it feels so good, we just can’t stop) and wasteful stewards of resources (when we get sick or bored of it, we just leave or throw it away). Entire industries prosper on our relentless, at times reckless and imprudent, desire for pleasure, enjoyment, and indulgence in what feels good.

So is that enough? Can we close our theory of happiness on these two key ingredients – need satisfaction and the allure of pleasure? If we just put up a strong moral fence to prevent theft, murder, exploitation, and bad business – and throw in some incentives for recycling and getting out to vote – human beings should be happy, right? No, that’s not right. Why? Because humans also require hope to be happy.

I will define “hope” as Holding Open a Positive Expectation for the future (see what I did there?). Most likely it has to do with the part of the brain most distinctive to our species, the prefrontal cortex, which gives us, among other things, an ability to grasp the Big Picture and take the Long View on things. This part of our brain isn’t fully online until sometime in our early to mid twenties, but once it is online our happiness depends henceforth on our belief in a promising future. Holding open a positive expectation for the future can keep us going when we are languishing physically, scratching the ground for satisfaction, having to cope daily with chronic pain or the absence of what once brought us deep enjoyment in life.

Young children are often idealized for their spontaneous and innocent engagement with present reality. They don’t worry about tomorrow. They don’t get caught up in their plans for the future, making strategies for what they want their lives to be like in some distant future, and then worry over what they can’t control. Oh, to be like that again! Please, just lop off my prefrontal cortex and let me revel in the limbic fairyland of my freewheeling imagination.

Hope doesn’t have to be either the escapism of wishful thinking or palliative therapy for a life in general decline. Holding open a positive expectation for the future is an essential human activity, and is, I would argue, the third key ingredient of happiness.

Hope doesn’t have to be either the escapism of wishful thinking or palliative therapy for a life in general decline. Holding open a positive expectation for the future is an essential human activity, and is, I would argue, the third key ingredient of happiness.

By holding the future open, we add cognitive aspiration to the emotional inspiration and physical perspiration of daily life. In believing that today is even now opening up into tomorrow, that this world and our life in it are already passing into the not yet of what’s still to come, we are liberated into our responsibility as co-creators of the New World.

And if, like Moses peering into the Promised Land but unable to enter, all we can do is hold the future open for our children and their children, hope is ultimately what makes life meaningful.

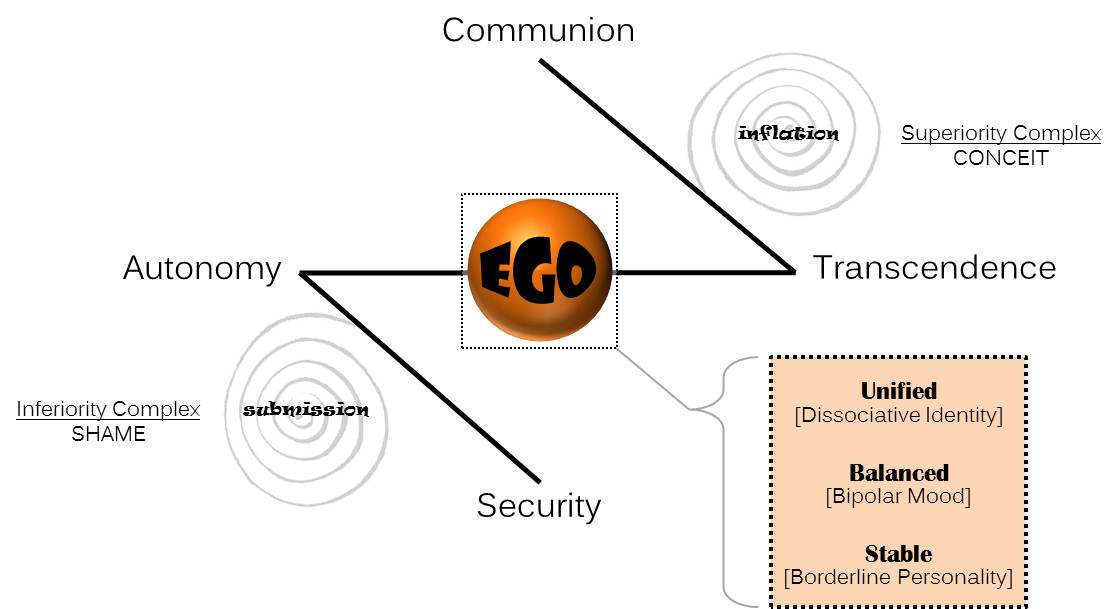

The diagram above illustrates this unitive theory of human nature and development according to the perennial philosophy, again with some clarifying insights from modern-day theorists. Let’s take a walk through the model and consider how it all fits together.

The diagram above illustrates this unitive theory of human nature and development according to the perennial philosophy, again with some clarifying insights from modern-day theorists. Let’s take a walk through the model and consider how it all fits together.

The most important discovery we can make as human beings – infinitely more important than how to win friends and influence people or think and grow rich – is that we exist. While that may sound much less interesting than the quest for wealth, status, and fame, the discovery of our existence – the full mystery and glory of being alive – makes everything else pale by comparison.

The most important discovery we can make as human beings – infinitely more important than how to win friends and influence people or think and grow rich – is that we exist. While that may sound much less interesting than the quest for wealth, status, and fame, the discovery of our existence – the full mystery and glory of being alive – makes everything else pale by comparison.