Today we seem to be at a moment of decision. Looking at the world’s main faith-traditions, ask yourself: Would I rather, along with Pope John-Paul II, turn away from Buddhism and turn first of all to the Muslim, because he like me believes above all else in the unity of God and in God’s revealed will? Or, alternatively, would I rather (possibly along with Pope Francis, but who knows for sure?), would I rather turn first to the Buddhist, and discuss with him the similarities and differences between our mystical and our ethical traditions? – Don Cupitt, Creative Faith: Religion as a Way of Worldmaking

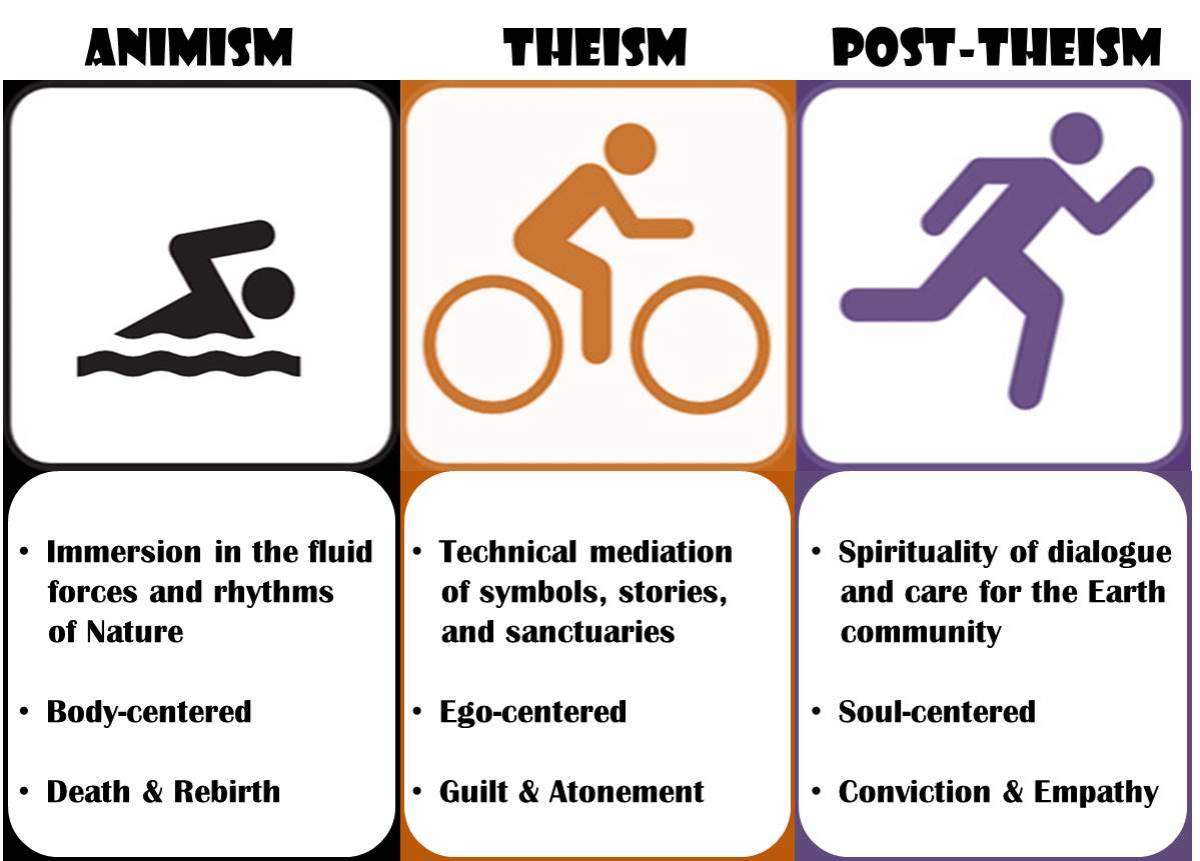

This quote from Don Cupitt struck me when I read it, in the way it corresponds to my own theory of religion’s development out of primitive animism, through the egocentric period of theism, and ultimately into a fully secular (this-worldly) post-theistic spirituality. Cupitt is a proponent of post-theistic Christianity who urges us to abandon the metaphysics of classical theology (deity, devil, angels, soul and the afterlife) in favor of a fully embodied here-and-now religion of outpouring love.

One way of reading Cupitt’s words is in the mode of comparative religion, where Christianity is positioned between non-theistic Buddhism on one side and hyper-theistic Islam on the other – hyper not intended as a synonym for extreme, militant, or fundamentalist, necessarily, but in the sense that Allah is ontologically separate from his creation and very much out there. Historical Buddhism can be regarded as a post-theistic development within Hinduism which abandoned a concern with gods and metaphysics for a commitment to end human suffering.

But we might also read Cupitt relative to a tension within Christianity itself, between its own hyper-theistic and post-theistic tendencies. I’ve argued elsewhere that Jesus himself should be seen as a post-theistic Jew who sought to move his contemporaries beyond the god of vengeance, retribution, and favoritism, to outdo even god in the practice of unconditional forgiveness and love of enemies. This tradition certainly represents a minority report in Christianity, whereas its orthodoxy has been more “Muslim” than “Buddhist” – much more about the Lord god, his exalted Christ, the Second Coming and Final Judgment than Jesus’ new community of love and liberty.

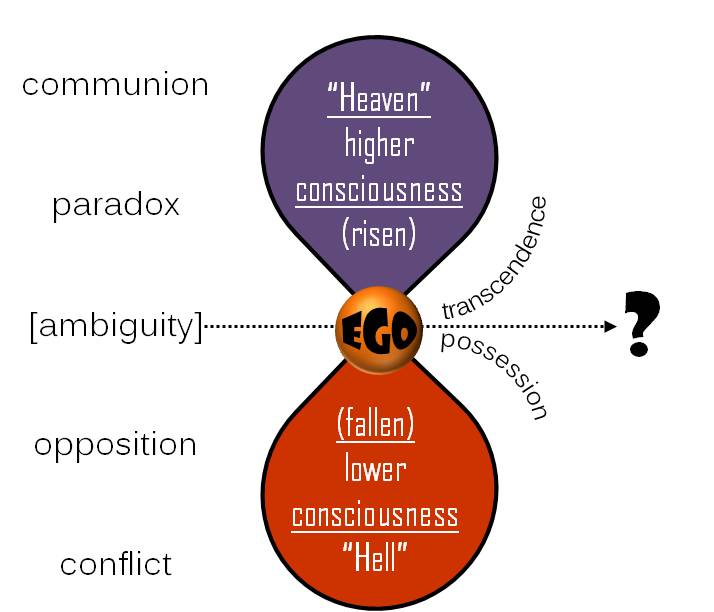

In my view, post-theism is the inevitable destiny of all religion. I’ve worked hard to distinguish post-theism from the more or less dogmatic atheism that is in fashion nowadays, where god’s literal and objective existence is disputed on logical, scientific, moral, and political grounds. Post-theism does not see the point in arguing the empirical status of a literary figure. Indeed, as a figure of story rather than a fact of history, god’s place in religion is rationally defensible.

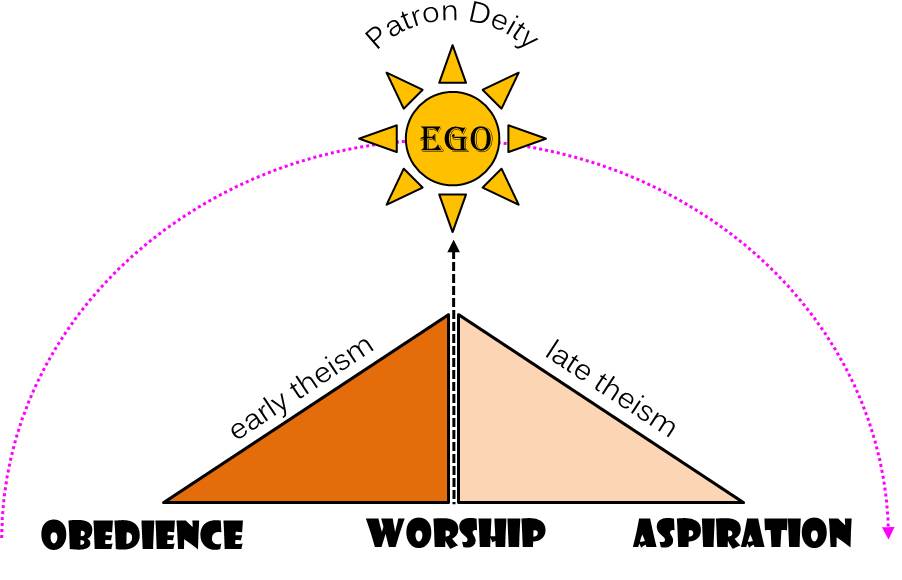

The problem arises when religion forgets that its god is a metaphorical representation of the providence all around us and of the grounding mystery within us. A literary character then becomes a literal being, the dynamic action of myth evaporates into the static atmosphere of metaphysics, and the supernatural object draws attention away from the real challenges before us. Tragically the opportunity of growing into our own creative authority is forfeited in the interest of remaining passively dependent on an executive-in-charge who is (coming back around again) a metaphor of our own making.

My own experience, along with what I observe in my friends and remember from my sixteen years in church ministry, has exposed a real “moment of decision” in spiritual development, where the healthy progression of faith would move us into a post-theistic (Cupitt’s “Buddhist”) orientation, but which is prevented by an overbearing theistic (Cupitt’s “Muslim”) orthodoxy that keeps it (in my words) “stuck on god.” The result is a combination of increasing irrelevance, deepening guilt, intellectual disorientation, and spiritual frustration – the last of which tends to come out, Freudian-style, in a spectrum of neurotic disorders and social conflicts.

Two popular ways of “managing” this inner crisis are to either suck it up and buckle down inside a meaningless religion, or else flip it off and get the hell out, bravely embracing one’s new identity as a secular atheist. From a post-theistic perspective, however, neither solution is ultimately soul-satisfying. Trying to carry on in the cramped space of a box too small for our spirit only makes us bitter and depressed, whereas trying to get along without faith in the provident mystery and in our own higher nature – what religion is most essentially about – can leave us feeling adrift in a pointless existence.

If Pope Francis as the figurehead of Catholicism can open his arms to other religions, embrace the scientific enterprise, advocate for the voiceless poor, and celebrate spiritual community wherever he finds it, then we might be encouraged to think that our “mystical and ethical” sensibilities can unite us and lead us forward. Perhaps the world’s interest in him has to do with the way his down-to-earth and inclusive manner resonates with something inside us that hasn’t felt permission to live out of our own center.

When the mystical (our grounding in the present mystery of reality) and the ethical (our connections to one another and to life in general) fall out of focus as functions of healthy religion, the doctrinal (what we believe and accept as true) and the devotional (our worship and sacrifice on behalf of what we regard as supreme in value and power) start to take over. What is intended to be a balanced, evolving, and reality-oriented system of meaning collapses into conviction and becomes oppressive.

When the mystical (our grounding in the present mystery of reality) and the ethical (our connections to one another and to life in general) fall out of focus as functions of healthy religion, the doctrinal (what we believe and accept as true) and the devotional (our worship and sacrifice on behalf of what we regard as supreme in value and power) start to take over. What is intended to be a balanced, evolving, and reality-oriented system of meaning collapses into conviction and becomes oppressive.

As our planet changes and the globe shrinks, as our economies become more intertwined and volatile, as technology is reshaping society and putting potentially catastrophic influence into the hands of more individuals, we need to come together for solutions. The old orthodoxies and their gods cannot save us. Neither terrorism nor complacency will see us through. We need wisdom now more than ever.

Yes, we are at a moment of decision.

Each of us is responsible for creating and maintaining a personal system of meaning called a world. It isn’t entirely our invention, as much of it, including the foundational elements known as assumptions, were installed by our culture (family and society) even before we acquired language. These pre-verbal dimensions of our world – which I also refer to as our worldview – should not be confused with the ineffable mystery of existence that fascinates mystics and inspires artists across the cultures.

Each of us is responsible for creating and maintaining a personal system of meaning called a world. It isn’t entirely our invention, as much of it, including the foundational elements known as assumptions, were installed by our culture (family and society) even before we acquired language. These pre-verbal dimensions of our world – which I also refer to as our worldview – should not be confused with the ineffable mystery of existence that fascinates mystics and inspires artists across the cultures.