There are a lot of highly concerned and rational people today who are being held back from stepping out, speaking up, and taking the lead into a better future for our planet. It’s not exactly that someone else is holding them back, even though that’s how many would try to rationalize their current situation. We’d like to think there is someone over there who is keeping us in our frozen state, and that if only they will leave us alone we will be happy.

There are a lot of highly concerned and rational people today who are being held back from stepping out, speaking up, and taking the lead into a better future for our planet. It’s not exactly that someone else is holding them back, even though that’s how many would try to rationalize their current situation. We’d like to think there is someone over there who is keeping us in our frozen state, and that if only they will leave us alone we will be happy.

This turns out to be little more than an excuse, however, because the real cause of our paralysis is internal to ourselves, not out there somewhere else.

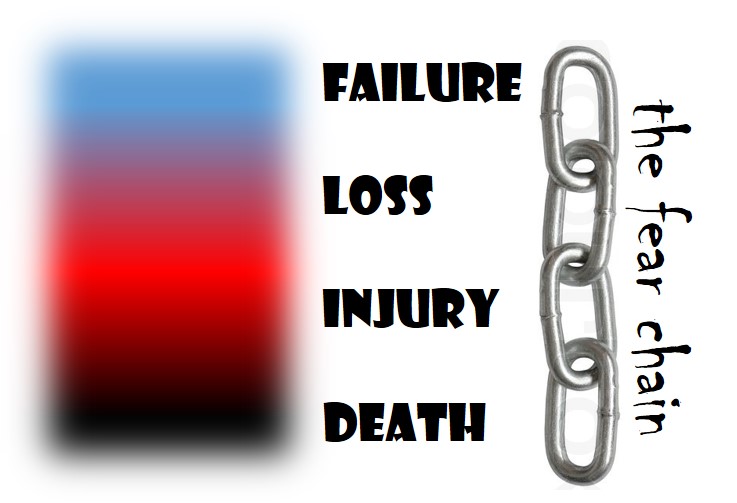

I propose the existence of something I’ll call “the fear chain,” which gets forged especially during those critical years of our early conditioning. Parents, teachers, coaches, and other handlers conspired in teaching us that certain things (and people) are dangerous – or potentially so. When we were very young we were cautioned against talking with strangers – along with playing in the street, running with scissors, and touching hot stoves. Such things were “dangerous,” and engaging with them would likely put us at significant risk.

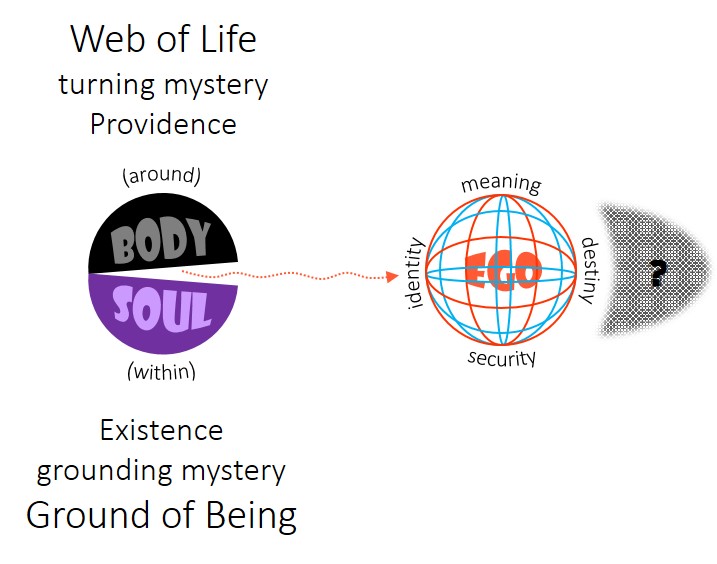

Whether or not they consciously realized it, these influential adults were servo-mechanisms in our socialization, whereby the animal nature of our body was trained to behave according to the rules and rhythms of cultural life. Already programmed by millions of years of evolution, our body came equipped with some basic instincts, the most persistent of which is our drive for self-preservation.

In some form or fashion, all the other instincts – for attachment, food, shelter, sex, and reproductive success – are variations of our primal commitment to staying alive.

This drive to stay alive might also be characterized as an innate fear of death, of avoiding or seeking escape from anything that threatens survival – particularly predators, venom, toxins and tainted food; along with genuinely high-risk situations of exposure, violence, or unstable and precarious environments. While not as primal, perhaps, anything that represented the possibility of injury was linked to our fear of death, since, if serious enough, an injury might very well result in our loss of life.

In this linking fashion, numerous secondary associations were forged and anchored to our compulsive need to live – and not die.

Such association-by-linking should make you think of links in a chain, and this is exactly how I am proposing that the fear chain comes into existence. A primal (and mostly unconscious) fear of death got linked out to situations, objects, and other people who presented a risk of injury to us. And just like that, the primitive energy dedicated to staying alive was channeled into attitudes and behaviors of avoidance, suspicion, and self-defense. From that point on, the possibility of injury started to drive what we did, where we went, and with whom.

This concept of a fear chain suggests that the paralysis many people feel today is a complication of how we have been socialized – not just when we were children but even now under the tutelage of the politicians, preachers, journalists, and jihadists who spin our collective perceptions of reality. In this case, those deeper fears of injury and death get linked to the more normal experiences of loss.

Almost as much as we fear losing our lives or losing our minds, we dread the loss of wealth and opportunity, of time and freedom, of the way we were, or what we thought we could accomplish and become.

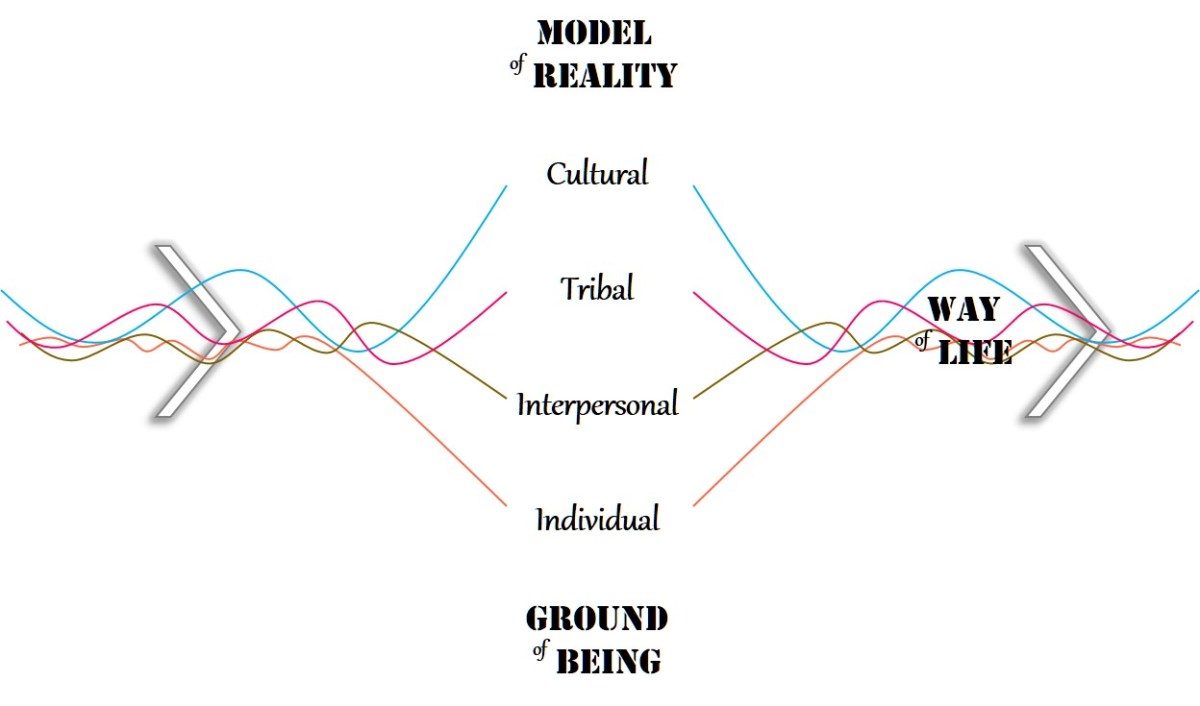

Socialization is largely dedicated to the project of constructing our identity – not what we are as human beings, but who we are as members of cultures, nations, classes, and tribes. This project is carried out through a process of forming attachments to the people, places, things, and beliefs that define us and form our horizon of meaning. Identity and attachment, then, are simply two sides of the same coin, with one (identity) the product of the other (attachment).

If we return to our natural and socially conditioned fear of injury, we can see how threats to our attachments amount to a kind of assault on our person. This is how the fear chain is forged with still another link: the (threatened or real) loss of an attachment is experienced as an injury to our identity, which anchors still farther down into our instinctual fear of death.

The stronger the attachment – that is, the more central it is to who (we think) we are – the more we fear losing it.

I wonder if the fragile construct of our identity – so many attachments, so much dependency – is what makes us so afraid of failure these days; of not being ‘successful’ or ‘good enough’. If we should try but fail, we run the risk of losing some aspect of who (we think) we are, suffering injury to our personal identity and (we irrationally believe) putting ourselves in peril of death itself. When a desired outcome isn’t achieved or we can’t get something perfect the first (or fiftieth) time, who we are and our place in the world is called into question. It’s best not to try, which allows us to keep the fantasy of identity safely above and ahead of us without the risk of being proven wrong.

Those who seek to generate an anxious urgency in us will typically use a narrative of terror to motivate us in the direction they want us to go. Such rhetoric is common from fundamentalist pulpits and during political campaigns, not to mention from those extremist wack jobs who seek to panic, disrupt, and destroy the life routines of innocent citizens. They are all united in their determination to unsettle us, tapping our amygdalas with messages of panic, outrage, and paralysis – the flight, fight and freeze responses hardwired into our brain circuitry.

For the relatively disengaged citizenry of liberal democracies, freezing is the majority option: we stop, stare, hold our breath and shake our heads, waiting for the stupor to pass before crawling back into our rut of life-as-usual.

My theory is that these narratives of terror are the sociocultural counterpart of the fear chain, one shaping the environment of our collective life and the other priming our nervous system for survival in ‘dangerous’ times. Even though a drive to survive and the fear of death may be instinctual, our chronic anxiety over losing ourselves – of losing who (we think) we are, along with the illusion of security and control that holds us together – is entirely conditioned and not natural at all.

Indeed, the intentional release of this bundle of nerves and dogmatic convictions is the Path of Liberation as taught in the wisdom traditions of higher culture.

The question remains as to how we might effectively transform our Age of Anxiety into a Kindom (sic) of Peace, where we love and honor the whole community of life on Earth. Years ago Paul Tillich coined “the courage to be” as the high calling of our human adventure. In defiance of the narratives of terror and breaking free of the fear chain, we can step out and speak up, investing our creative authority in the New Reality we want to see.

It will take more than just a few brave souls. And it will require that we move out of complacency, through protest, into a very different narrative.

progresses, but whose core identity is consistent from one scene to the next.

progresses, but whose core identity is consistent from one scene to the next.

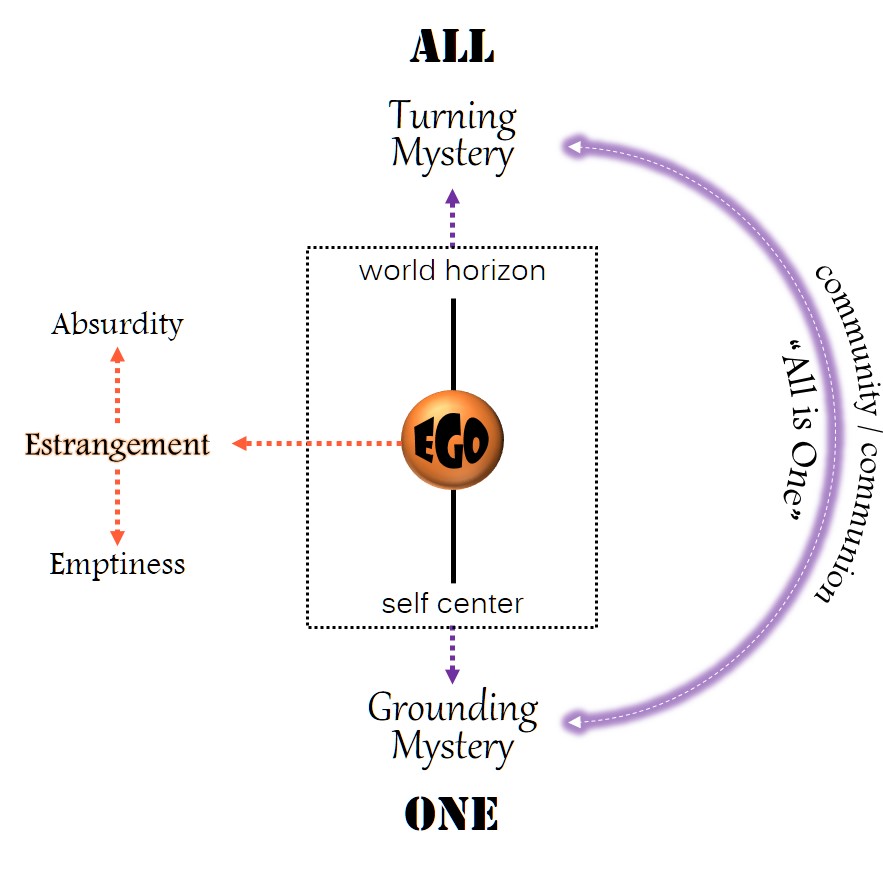

One of the critical achievements on the long arc to human fulfillment is a capacity for getting over ourselves. Our chronic problems and pathologies are complications of a failure in this regard. We get tangled up, hooked, and held back from our true potential and end up settling for something we aren’t. Instead of focusing on the problem, however, I would rather look more closely at what fulfillment entails.

One of the critical achievements on the long arc to human fulfillment is a capacity for getting over ourselves. Our chronic problems and pathologies are complications of a failure in this regard. We get tangled up, hooked, and held back from our true potential and end up settling for something we aren’t. Instead of focusing on the problem, however, I would rather look more closely at what fulfillment entails.