In his popular lectures on the topic, Joseph Campbell would frequently start out with a definition of mythology as “other people’s religion.” Curiously the assumption of insiders is that the depiction of their god in the sacred stories of scripture came by supernatural revelation, while stories of other deities outside their tradition are quickly dismissed as just mythology.

A purely objective consideration of myth across the religions will not be able to distinguish which stories were “revealed” (by god) and which were “produced” (by humans). The god of our Bible is not less violent or more merciful than gods we can find in stories elsewhere. But even in the polytheistic age of the Bible when other gods were acknowledged if not honored and worshiped, we find this tendency to regard other people’s religion as generated out of ignorance rather than by illumination.

So let’s stay with the Bible for now, and ask why so many believe in the existence of Yahweh*, the patron deity of Jews and Christians. The popular assumption, once again, is that they believe in Yahweh’s existence because the Bible (the principal resource of Judeo-Christian mythology) contains historical accounts and eye-witness reports (encounters, sightings, and auditions) of the deity. Yahweh created the cosmos, liberated the Hebrews from Egypt, revealed himself to the prophets, and sent his son for our salvation. These things are taken and accepted as facts – historical, objective, and supernaturally validated.

What I’m calling the supernatural validation of biblical stories can be analyzed into three closely related but independent claims. First, the Bible is an inerrant resource for our knowledge of Yahweh. Every word – or in a softer variant of the inerrancy doctrine, the intention behind every word – is the revelation of Yahweh to those he elects to save. To prove Yahweh’s existence by appealing to the Bible as his infallible revelation to us is an argument of obvious circularity, so we hasten on to the next claim, which is that the Bible records literal accounts of Yahweh’s self-revelation to people much like us.

This is how to escape the fatal circularity of the inerrant Bible argument: Because the stories of the Bible are factual reports of events in history, however miraculous and supernatural, the real anchor for our knowledge of Yahweh’s existence and character is human experience. Prophets and visionaries, but also average folks like you and me, were granted the privilege of divine visitations and apocalyptic visions. They were actual witnesses; their accounts were taken down with perfect accuracy and provide us with what we know about Yahweh. If the biblical stories were not grounded in actual events outside the Bible, they would be nothing more than … well, myths.

Even with that critical move, however, believers are still on shaky ground, for how can we know that these historical “revelations” were not really hallucinations of something that wasn’t there? So-called ecstatic experiences (e.g., clairvoyance, glossolalia, out-of-body experiences, “hearing voices”) are observed among patients in mental clinics and state hospitals around the world today. I suppose it could be argued that these are the true charismatics of our age, though tragically misunderstood and wrongly diagnosed. But who’s to say that those visionaries behind the Bible were not mistaken or mentally disturbed?

To answer – and effectively silence – this question, the third and final claim for the supernatural validation of our knowledge of Yahweh is that these visionaries didn’t just “see things,” but that he showed himself directly to them. Authorization for the orthodox doctrines concerning god’s nature, character, attributes and accomplishments therefore transcends both the Bible and human experience.

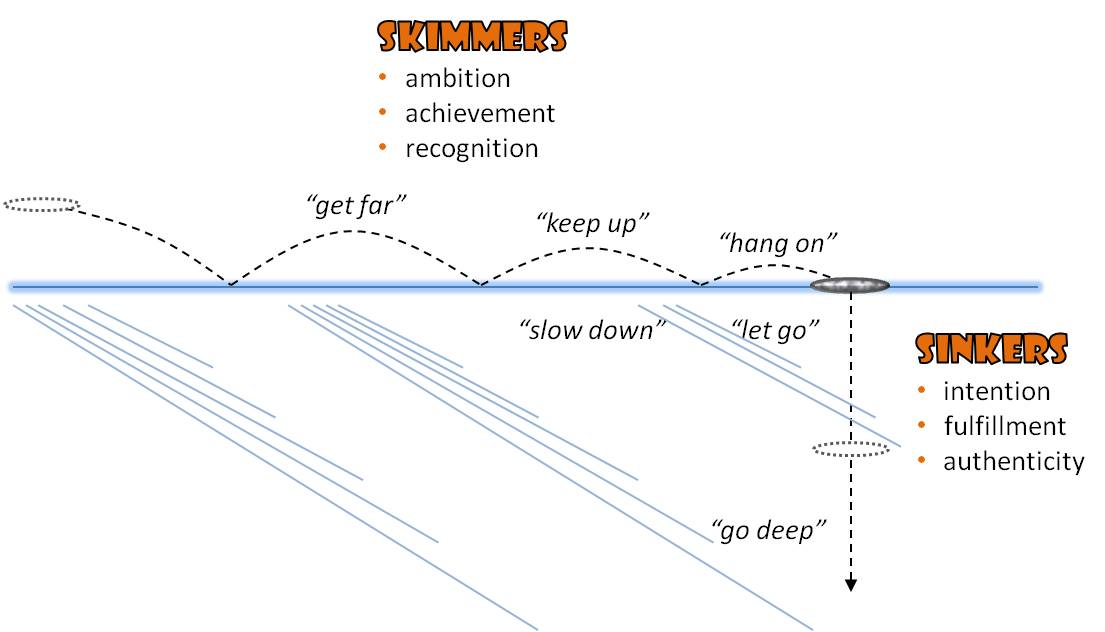

The argument is thus that (1) Yahweh exists (out there as a separate being) and (2) revealed himself to people much like us, who then (3) recorded their experiences and facts about Yahweh in the inerrant resource of our Bible. Even though Yahweh isn’t speaking out of burning bushes, parting water, multiplying loaves, or raising dead people back to life anymore, the faith of a contemporary true believer is measured by how willing he or she is to simply trust that the same deity is out there, watching over us, and getting ready to ring down the curtain on history.

But what if Yahweh doesn’t exist – and by “exist” I mean out there as a separate entity, “above nature” (supernatural) and metaphysically real? What if no one has ever encountered this deity in the realm of actual human experience? What if the Bible isn’t a factual record of extraordinary encounters and miraculous interventions?

What if, that is to say, Yahweh is a literary character, the principal actor and prime mover in the collection of stories that shaped the worldview of Jews and Christians – but not a literal being?

Of course there are people today who claim to have had personal experiences of the biblical deity – or any number of countless other gods and goddesses, spirit guides, angelic or demonic beings, fairies and departed souls. Perhaps because we want to hold open the possibility of higher dimensions to existence, or because we can’t conclusively disprove their reality, or maybe we don’t want to come across as judgmental, simple-minded or faithless, we let the popular discourse continue unchecked. Who knows, but perhaps these individuals are genuinely gifted. Could they be seeing and hearing things from which our ignorance or skepticism prevents us?

Someone has to say it, so I will: No.

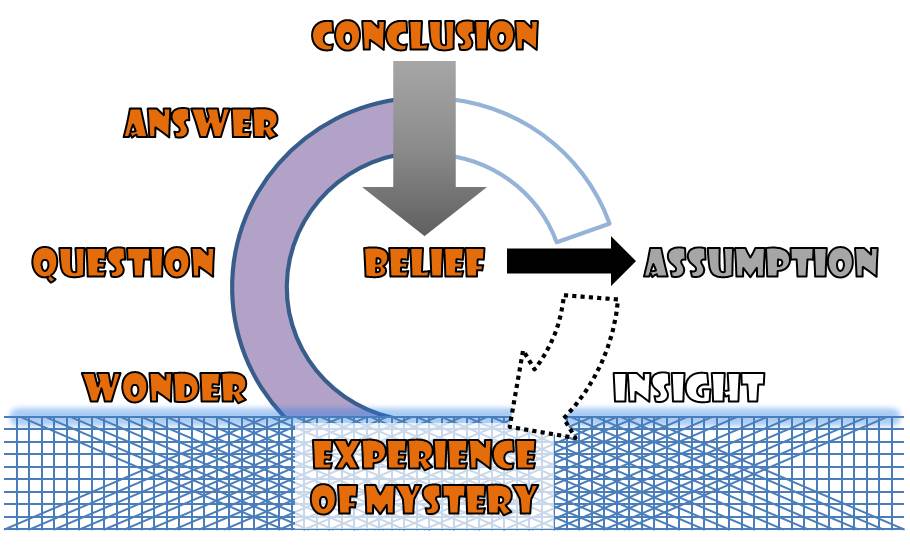

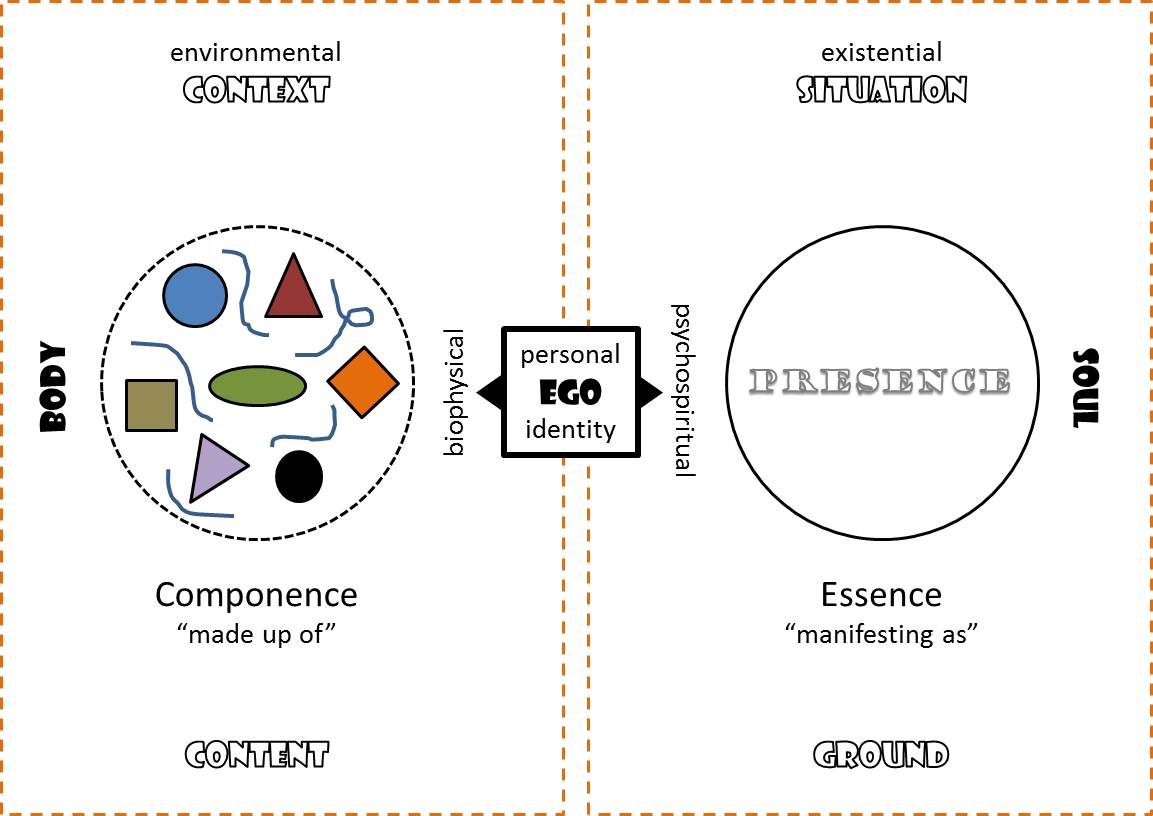

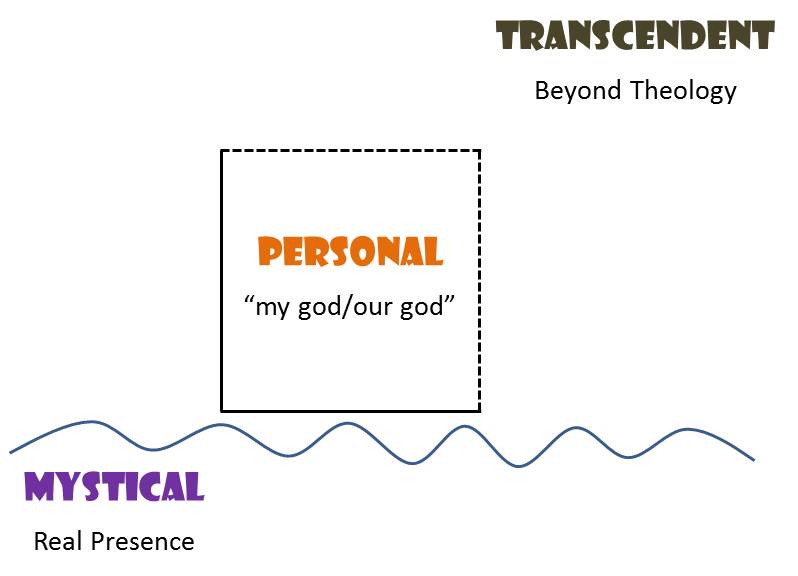

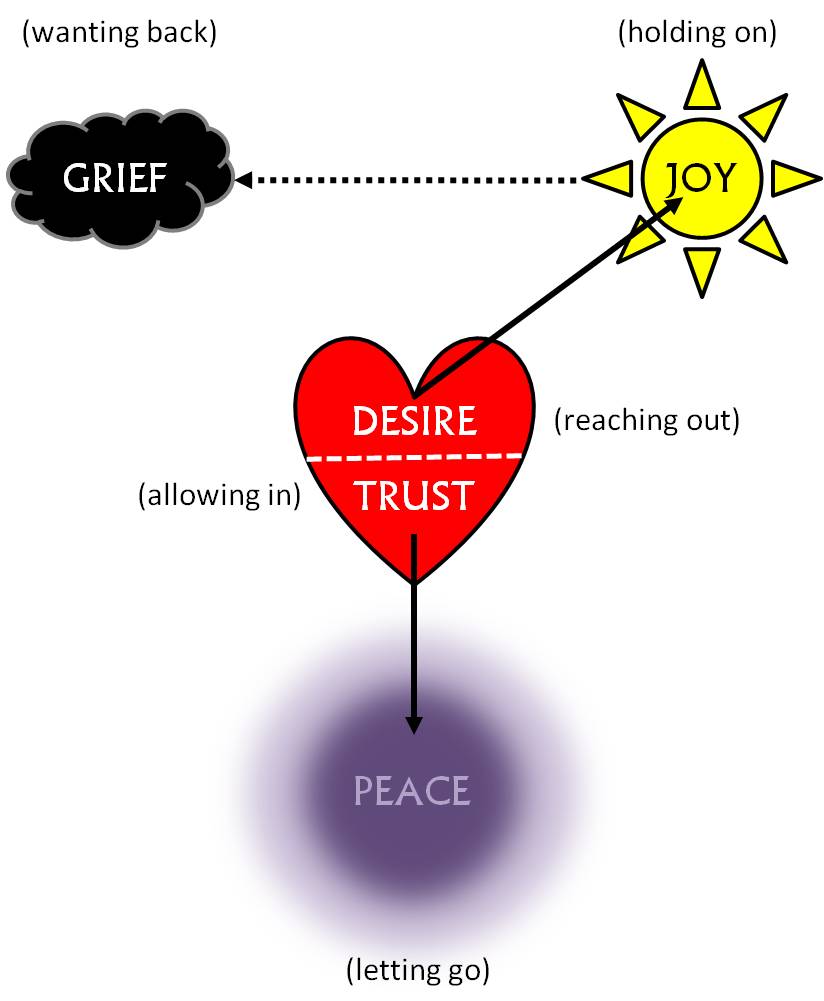

Metaphysical realism – belief in the existence of independent realities outside the sensory-physical universe – was the inevitable consequence of mythological literalism. When the myths lost their tether to sacramental celebration, ritual reenactment, and the contemplation of mystery, they floated up and away from daily life to become “timeless” accounts, ancient records, and long-lost revelations. But before they were taken literally, while they were still serving as drama-poetic expressions of experience and the narrative structure of meaning, myths were fictional plots bearing the life-orienting metaphors on which human security, community, and the shared search for significance depend.

The stories of the Bible are indeed myths (from the Greek mythos, a narrative plot), not to be taken literally but engaged imaginatively. Much of the worldview they promote and assume is out of date with respect to our current science, politics, ethics, and spirituality. At the time of their composition, the biblical myths were very similar to those of other tribes and traditions, but with Yahweh (rather than some other deity) as the metaphor of the community’s dependency on the earth, its place among the nations, its origins and destiny, and its moral obligations.

As human culture evolved, so did Yahweh. Indeed, one of the principal functions of a deity is to model (in example and command) the preferred behavior of his or her devotees. The storyteller is sometimes at the leading edge of this evolution, as when a minority voice among the prophets began representing Yahweh as unimpressed (even offended) by the sacrificial worship of his people, demanding instead their care for widows, material help for the poor, and inclusion of the marginalized. Later, Jesus of Nazareth gave the wheel of evolution another turn when he began to tell stories of Yahweh’s unconditional forgiveness of sinners (love for the enemy).

At other times, those telling the stories and thereby controlling theology were motivated by less noble, even base and violent impulses. Yahweh’s wrath and vengeance as represented in the myths subsequently provoked and justified similar behavior in his devotees. Depending on what you are looking to justify in yourself or get others to do, chances are you’ll find Yahweh endorsing it somewhere in the Bible.

I’ve defined myths as fictional plots bearing life-orienting metaphors and shaping our view of reality, with the deity chief among these metaphors. Rather than looking outside the stories for facts that might establish their truth, I’m arguing that we need to look deeper inside the stories to the human experience of mystery and our quest for meaning that inspired them.

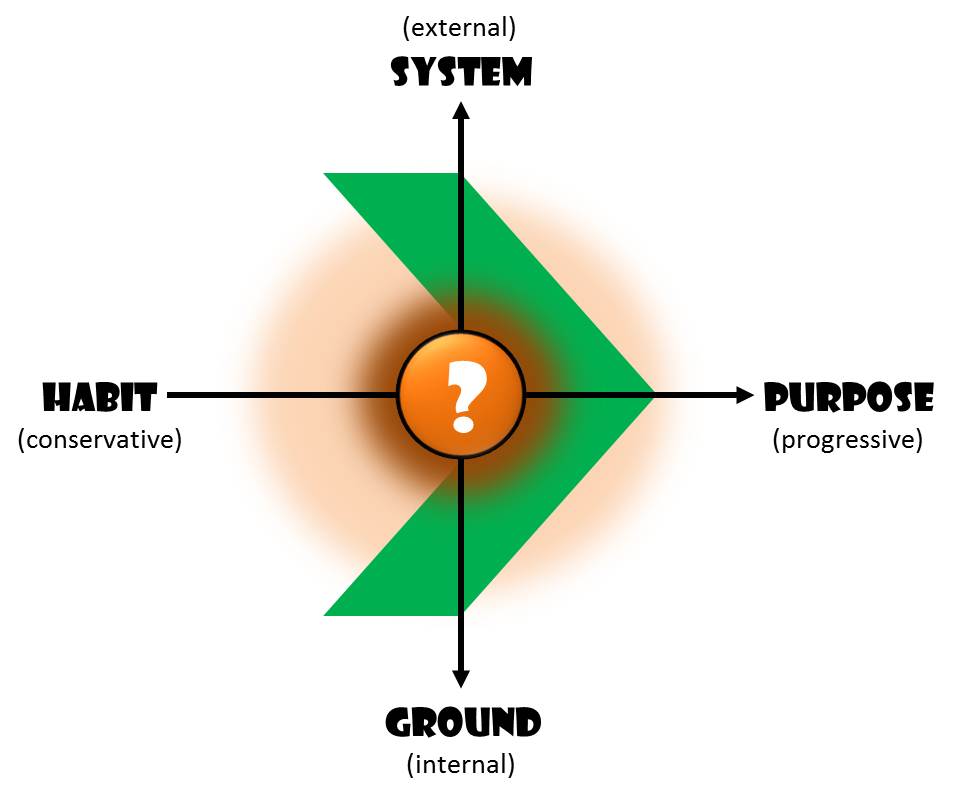

Theism insists on the objective existence of god, while atheism rejects it. Post-theism is our growing awareness that the argument, one way or the other, just might be distracting us from the real challenge at hand.

*In reading the name Yahweh, and throughout the continuing scriptural tradition, a title (Adonai, The Lord) was used in its place as an expression of reverence.