In my efforts to define what I mean by ‘post-theism’ (as distinct from other uses of the term you might find out there), it’s been critically important not to confuse it with straight-up atheism on one side, or on the other with clever spins on the ‘post-‘ idea that contemporary Christian theism is attaching to the ’emerging church’ movement (for example). My construction is intended to name a stage of religion that comes decisively after theism, as a transformation beyond it that holds the promise of facilitating human spiritual evolution to the next level, without getting hung up in debates over the existence of god.

In my efforts to define what I mean by ‘post-theism’ (as distinct from other uses of the term you might find out there), it’s been critically important not to confuse it with straight-up atheism on one side, or on the other with clever spins on the ‘post-‘ idea that contemporary Christian theism is attaching to the ’emerging church’ movement (for example). My construction is intended to name a stage of religion that comes decisively after theism, as a transformation beyond it that holds the promise of facilitating human spiritual evolution to the next level, without getting hung up in debates over the existence of god.

This type of post-theism acknowledges god as a construct of the mythopoetic imagination, not as a literal being but rather the principal figure in sacred stories – more properly, then, as a literary being. Our representations of god serve the purpose of orienting us in an intelligible universe (regarded as the creation of god), inspiring us to worthy aims (identified with the will of god), and guiding our ethical development as persons into virtues of community life (glorified in the character of god). The ultimate aim, ethically speaking, is for the devotee to so consciously internalize and intentionally express the virtues of god’s character that the need for an objective ideal is permanently transcended. Human evolution continues from that point, on the other side (after: post) of god.

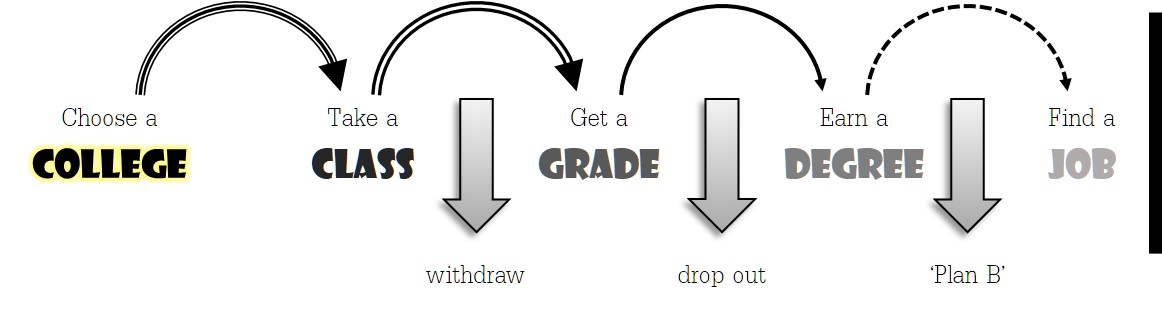

It helps considerably if we don’t treat theism as one thing, as a singular religious phenomenon which must either be accepted or rejected en bloc. Its development out of primitive animism arches over many millenniums, and its career has been one of steady progress (with frequent setbacks) into a spirituality and way of life more mystically grounded, ethically responsible, and globally connected than before. These very developments now threaten the more tribal forms of theism which are losing relevance faster than ever despite their appeal to insecure and extremist types. In this post I offer a lens for understanding theism in its development, tracking its ‘leading indicator’ in ego’s rise to maturity – and beyond.

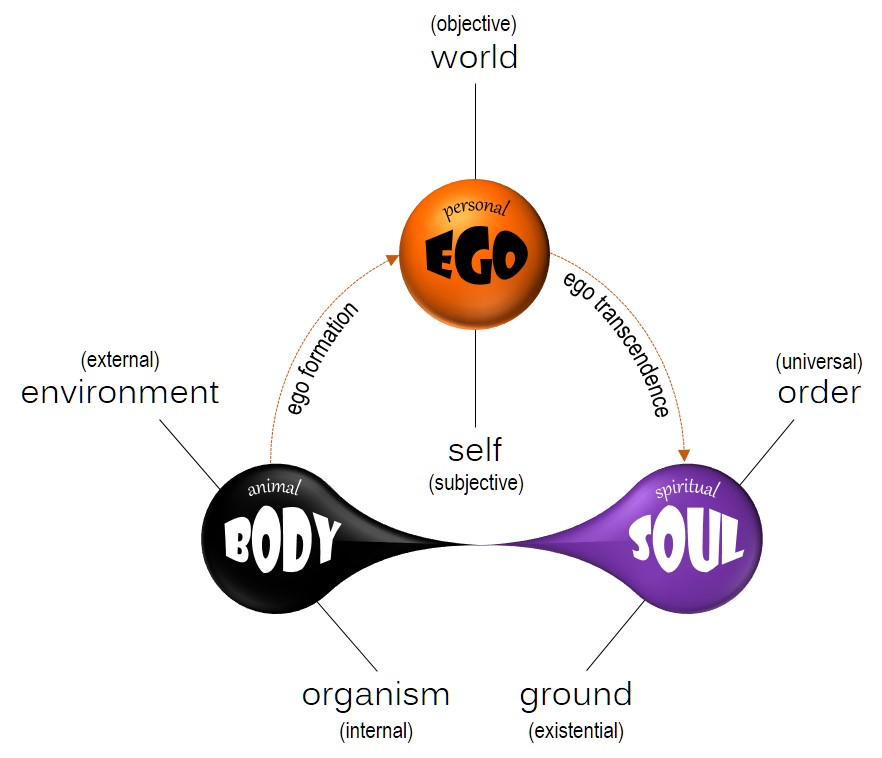

The major phases of theism correlate to the career of personal identity (ego) in the human beings responsible for it as a worldview and way of life. (We still need to be reminded of the fact that religions are human inventions created for the purpose of linking concerns of daily life back to the present mystery of reality, represented and personified in the construct of deity.) We can conveniently analyze ego’s career into an early, middle, and late phase, where personal maturity in a stable, balanced, and unified self (the markers of ego strength) is the aim. My theory simply regards these distinct phases as stages, in the sense of platforms that provide the developing ego identity with shifting orientations in and perspectives on reality.

As a constructivist it should be clear by now that I see personal self-conscious identity (ego) as something that is not essential to our nature as human beings, which is to say that it is not in our given nature as products of evolution. Instead, it is socially constructed in the cultural workspace of our tribes. The taller powers (our parents, other adults and older peers) shape us into who we are, as a central node in the complex role-play of tribal life. We then perform our various roles according to the rules, values, and expectations (i.e., the morality) of the social groups in which we have an identity.

In the diagram above, this construction of ego identity (color-coded orange) is tracked in its slow progress through the essential aspects of our nature, body (coded black) and soul (purple). Depending on where we take our perspective in ego’s development, the relationship of these two aspects to each other is differently construed – in terms of ‘opposition’, ‘reconciliation’, or ‘communion’. These terms are thus offered as key concepts in our understanding of ego’s development, as well as that of theistic religion.

In the opposition phase, our separate center of personal identity (ego) is not very well defined. The very imposition of ego, however, causes a split in consciousness where an inner subjective realm is gradually divided from an outer objective realm, or ‘soul’ from ‘body’. Whereas soul and body in our essential nature are simply the introverted (intuitive-spiritual) and extroverted (sensory-physical) aspects of an evolved consciousness, our executive center of personal identity throws them into opposition. Now ‘I’ (ego) have a soul and a body, and the challenge becomes one of constructing a meaningful relationship between them.

This is where we find all those wonderfully complicated and emotionally charged stories (myths) about the separation of matter from spirit, of body and soul, giving account of how we happened into this conflicted state in which we presently find ourselves. It might get worked out into a fabulous mythology that puts god in opposition to the world as a bodiless and transcendent entity existing apart from our fallen carnal nature. Elaborate rituals must be invented, and then spun back to the people as revelations, that can provide a necessary atonement for resolving the negative conditions of our ignorance, guilt, and selfishness.

As personal identity continues to develop, these opposing forces of body and soul are gradually reconciled – brought together in a healthier marriage rather than striving in conflict. While traditionally interpreted in light of the older orthodoxy of opposition, Paul’s reflections on the person of Christ as one in whom ‘god was reconciling the world to himself’ (2 Corinthians 5:19) – that is to say, as one in whom body and soul were fully united in his essential nature – might be seen as evidence of this shift in perspective where ego (the Christ ideal) has progressed beyond a body-soul opposition and more into its own stable center of identity. At any rate, there is no doubt that Paul helped to move theism past the opposition of Two (god and humanity) and toward a synthesis into One (a deified humanity or incarnate deity).

As an aside I should note that Christian orthodoxy for the most part has ignored, and perhaps even willfully rejected, a theism of reconciliation for a reinstatement of the older theism based in opposition. Jesus came to be regarded not as the ‘New Man’, in line with Paul’s meditations, but as the key player in a transaction of salvation whereby our guilt was paid off and god’s wrath against sin was appeased. Even though humanity’s criminal record was expunged, god and the world remain essentially separate from each other.

This derailment of Christian orthodoxy from the intended path of theism’s evolution has, I am arguing, prevented the religion from progressing into its post-theistic phase. Despite the efforts of Jesus, and Paul after him, to move theism past the oppositions of god-versus-world, soul-versus-body, self-versus-other, us-versus-them, into a new paradigm where such divisions are transcended and made whole, Christian churches today remain locked in a pathological dualism. But we still need to consider what a full embrace of its post-theistic destiny would look like.

In my diagram, the distinct and separate ego has reached the point in its development where ‘me and mine’ no longer limit a fuller vision of reality. While a sense of oneself as a person continues to be in the picture, the sharp division of body (black) and soul (purple) gives way to a blended continuum of animal and spiritual life. We are ‘spiritual animals’ after all, and now our awareness and agency as persons can move us into a new but still self-conscious mode of being. My name for this mode of being is communion, literally ‘together as one’. There is no god on one side and the world on another. No souls separate from bodies awaiting deliverance to a postmortem paradise. No ‘us’ on one side and ‘them’ on the other.

We are all one together. Nothing, really, is separate from the rest. The realization of this oneness, however, depends on our ability to appreciate ourselves (and all things) as manifestations of the same mystery. Such a profound appreciation – Jesus and other luminaries called it love – will fundamentally change how we live.