From time to time it’s important to take a step back from the detail work of theory-building in order to catch hold of the big picture of what you’re doing. I’ve offered up some wide-ranging ideas on such topics as consciousness, spirituality, post-theism, and human self-actualization, and now I’ll try to bring together the major sight lines of a larger vision.

From time to time it’s important to take a step back from the detail work of theory-building in order to catch hold of the big picture of what you’re doing. I’ve offered up some wide-ranging ideas on such topics as consciousness, spirituality, post-theism, and human self-actualization, and now I’ll try to bring together the major sight lines of a larger vision.

Backing up conceptually as far as we can brings us to the origins of our present universe. Contemporary cosmology (study of the cosmos) is coming ever closer to a grand unified theory (GUT) that can account for the flaring-forth of energy into the most basic constituents of matter – in an event (or ‘singularity’) popularly known as the Big Bang. Since the fabric of space-time is thought to have emerged at this point, there is no way for scientists to determine when (i.e., at what moment in the past) this occurred, but they have calculated the age of our universe to be somewhere around 14 billion years old.

In my diagram I have represented this primordial transformation of energy crystallizing into the subatomic latticework of matter as the elementary stage of the universal process (or ‘universe’ for short). As I will continue to use this convention of stages, it’s important to understand that I don’t regard a stage as merely a formative period in the historical past that has been left behind. In addition to thinking of it as a previous era in the course of change, I’m using ‘stage’ in its spatial connotation as well, as a supporting platform for ongoing progress. In other words – and this should not come as a surprise – the elementary stage in the rise of our present universe is still very active, providing the energetic and material support to what we’ll look at next.

Stage 2 of the process (comprised of levels 3 and 4) is named the evolutionary stage, since this is when (and where) life first emerges. Technically speaking, the term ‘evolution’ should be reserved for the adventure of life (on our planet and possibly elsewhere) and not for the quantum dynamics at work in the energetic transformations of matter. Life introduces something unique and unprecedented in the way it ‘rolls out’ (or evolves) into more adaptive and complex organisms over time. Organic names the basic life-force, while sentient is how the evolution of life has gradually produced organisms that are more aware, responsive, and engaged with their environment.

At Stage 3 is where a uniquely human form of consciousness makes its appearance. Ego is Latin for ‘I’, referring to that separate center of personal identity which is both a construct of social engineering and the agent of social development. Our animal nature as human beings tracks downward into the instincts and urgencies of survival, while ego ‘sets the stage’ for a transpersonal breakthrough to spirituality and higher wisdom.

A critical condition of this breakthrough experience is provided in the developmental achievement of ego strength, evident in a personality that is stable, balanced, and unified. This threshold (at level 5, egoic) is where a lot of my blog posts focus in, since a lack of ego strength – presenting in a neurotic tangle of insecurity, attachment, and inflexible convictions – is at the root of much of our suffering. I’ve frequently pointed out how some forms of religion, particularly of the theistic type, use this neurotic tangle to promote dogmatism, bigotry, redemptive violence, and otherworldly escapism.

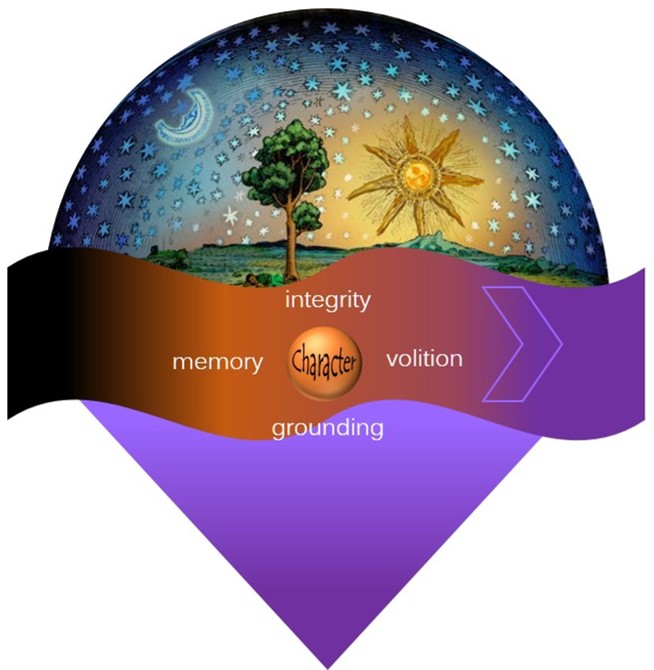

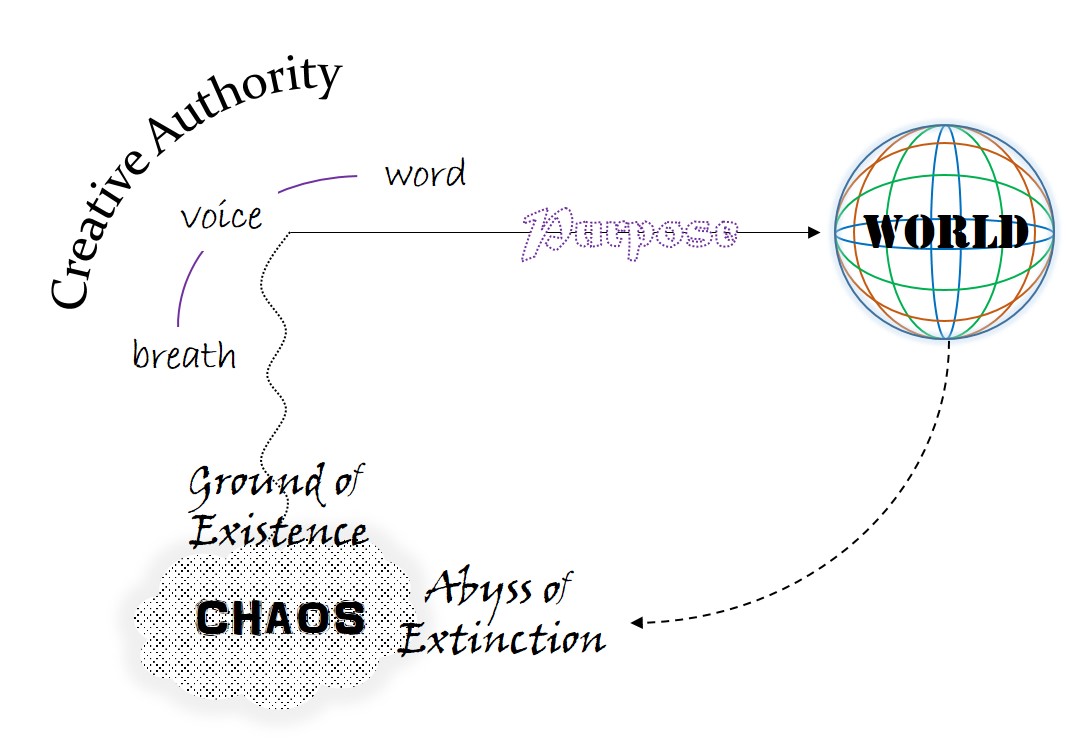

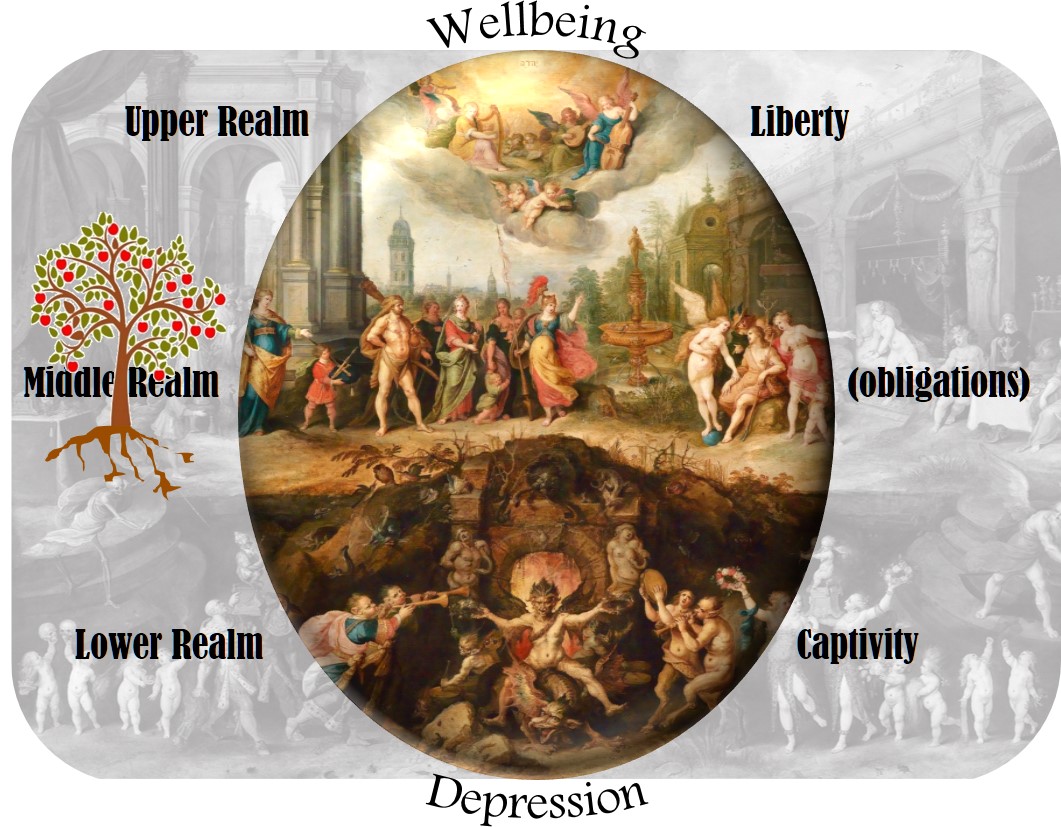

Let’s assume for now that ego strength is achieved. What’s next? The transpersonal level opens in two distinct paths of spirituality, one leading inward to what I call the grounding mystery, and the other outward to the turning mystery. The grounding mystery (or more philosophically, the ground of being) is not something else underneath it all, but the creative source of consciousness within us. In other words, you don’t go looking for it out in the world – or rather, you might try to find it in the world but your quest will come to frustration. This is why the mystical turn utilizes a variety of practices and methods for conducting an inward descent of ego release to the mystery within.

A second transpersonal path takes an ethical turn, beyond ego but this time in the direction of an ascending involvement in ever-larger horizons of participation. In this case, personal identity does not drop away, as on the mystical path, but instead serves our upward leap into genuine community where ego doesn’t dissolve but connects in relationship with others. Historically, the quality of this connection proceeds in correlation with our cultural representations of the divine ideal (summarized in such virtues as creativity, benevolence, equanimity, and wisdom), which it has been the responsibility of organized religion to depict in myth, art, liturgy, and theology. (For the reasons given earlier, this responsibility of religion hasn’t been fully understood or consistently fulfilled.)

As it follows these two distinct transpersonal paths, spirituality advances our quest for a deeper center and a higher purpose. Just as our center in sentience is deeper than our center in personal identity, progress in this direction also opens our ethical considerations to a correspondingly larger horizon – beyond just ‘me and my own’ to all sentient life. The higher purpose in this case is not a set of orders legislated from above (we have already moved into post-theism at this point), but the more far-reaching principles that concern our life together with all living things on this planet. What is our responsibility to the greater community of life?

My general theory regards the cultural stage of human evolution as trending inevitably into transpersonal realms of awareness and action. While still only a relative few have achieved this breakthrough – whether held back by their own neurotic entanglement or by social institutions (e.g., family, class, religion) that are getting in the way – all the signs are indicating a planet-wide spiritual awakening. The counterforces will not likely fade away gently, however, but can be expected to redouble their efforts in holding us captive.

Insecurity, selfishness, hatred, and terror cannot be overcome by violence. We must transcend them, which we do by acknowledging them, understanding them, and then simply letting them go.

Most of us have had the experience of getting our vision diagnosed by an optician. A fancy instrument, called a phoropter, is maneuvered in front of our face and positioned on the bridge of our nose. As the technician clicks various lenses over each eye and we try to read some letters or view a scene, we are asked to judge which of two clicks makes the picture more distinct. Eventually we arrive at the specific power of refraction that will compensate for the weakness and astigmatism of our unaided eyesight.

Most of us have had the experience of getting our vision diagnosed by an optician. A fancy instrument, called a phoropter, is maneuvered in front of our face and positioned on the bridge of our nose. As the technician clicks various lenses over each eye and we try to read some letters or view a scene, we are asked to judge which of two clicks makes the picture more distinct. Eventually we arrive at the specific power of refraction that will compensate for the weakness and astigmatism of our unaided eyesight. Other cultures, both ancient and contemporary, view reality through a different lens from that of Western individualism. Instead of looking at the collective through a preference for the individual, they define an individual through the lens of community. It’s not that the individual is unimportant; rather, the individual only makes sense as a function of the whole. Self-sacrifice on behalf of one’s community takes precedence over competition among individuals for self-advancement.

Other cultures, both ancient and contemporary, view reality through a different lens from that of Western individualism. Instead of looking at the collective through a preference for the individual, they define an individual through the lens of community. It’s not that the individual is unimportant; rather, the individual only makes sense as a function of the whole. Self-sacrifice on behalf of one’s community takes precedence over competition among individuals for self-advancement.