The role of religion for millenniums has been to connect (or tie together, from the Latin religare) the inner and outer realms of human experience. This sounds odd nowadays, given that religions the world over are presently fomenting (or at least justifying) violence against minorities and outsiders in the name of their gods, as they work to successfully separate the true believer from this fallen and sinful world.

The role of religion for millenniums has been to connect (or tie together, from the Latin religare) the inner and outer realms of human experience. This sounds odd nowadays, given that religions the world over are presently fomenting (or at least justifying) violence against minorities and outsiders in the name of their gods, as they work to successfully separate the true believer from this fallen and sinful world.

But as with everything else, a thoughtful consideration of religion needs to distinguish between its essential function (by design, so to speak) and what it has become under the various conditions of history, geography, and culture. If this or that religion exploits our natural insecurity, heaps guilt on our heads, and pulls us into spiritual depression, should we just reject religion itself as a negative force on our planet? Increasingly this is the popular opinion of secular minds.

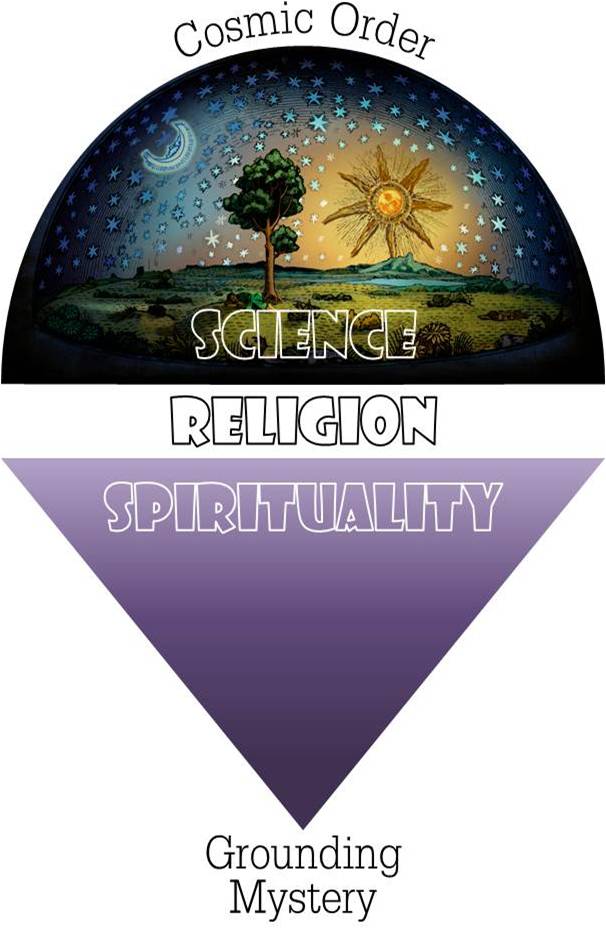

Whatever its peculiar manifestation, however, religion will always serve a necessary function in human culture – at least this is my argument. Its particular form (animistic, theistic, or post-theistic) and denomination (totemic, Southern Baptist, or Zen Buddhist) is more or less a “sign of the times,” but the phenomenon of religion itself is critical to our ongoing evolution as a species. The reason is that our quest for a meaningful connection between the inner and outer realms of experience corresponds to the nature of human consciousness itself.

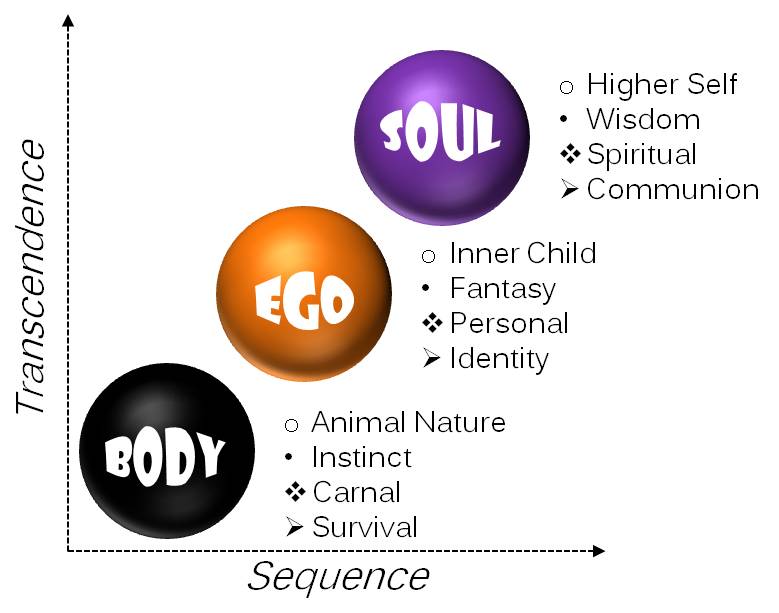

Simply put, the conscious self is aware in two primary directions – outward to its surroundings and inward to its own deep interior. Take a moment to notice this for yourself. The physical apparatus of your body and brain has the task of coordinating your behavior with the changing conditions of circumstance, in a way that is both adaptive and advantageous. Success-oriented behavior (in this sense) doesn’t really require much conscious intention; life on this planet evolved for millions of years without it. But with the advent of more sophisticated nervous systems came a “surplus” of conscious awareness, which in humans (at least) opened attention to the deeper and larger mystery of existence. Homo Philosophicus.

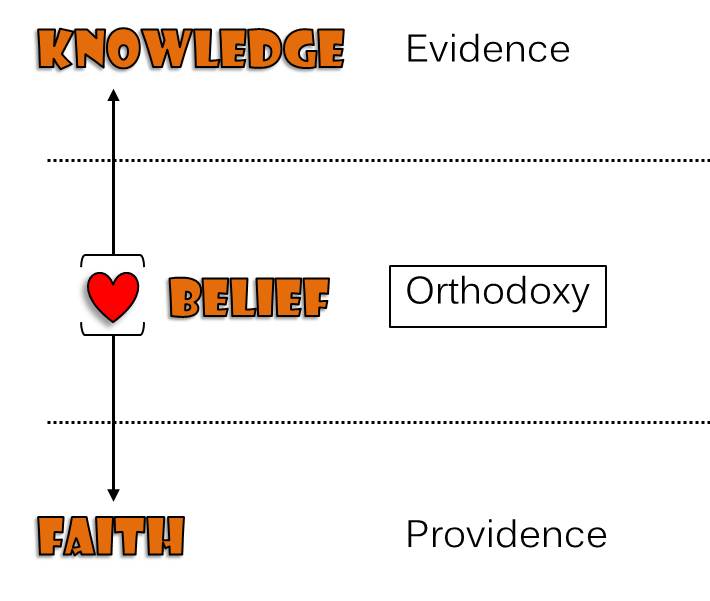

What I’m calling the deeper mystery of existence is the inner realm whence consciousness itself arises. At some inner threshold of this descending awareness, the ego, referring to that contraction of self-possession acknowledged as “I-myself,” gets loose in the joints and begins to fall apart. As we would expect, this threat to its own self-possession generates confusion and anxiety in the ego, which may persuade it to resist further descent and recover control. But this is precisely where religion, in its role as counselor and guide to the deeper mystery, encourages the nervous psychonaut (“soul explorer”) to let go in full surrender to the provident ground of being.

Such inward exploration and expansion of consciousness into its own depths is what I mean by “spirituality.” Because this is the inner realm of our human nervous system, it seems safe to assume that the nature of experience at this deeper register of consciousness is virtually the same today as it was many thousands of years ago. Getting there might have been more of a challenge back then, given the urgencies of survival in the forest or savanna, but I can imagine a distant hominid ancestor dropping into contemplative awareness on a warm African morning.

Spirituality is inherently mystical, or at least it has a strong tendency to sink into the grounding mystery where our separate self (ego) dissolves into an ineffable presence. In this space grows an awareness that existence itself rests in, rises out of, and returns to essential communion. And yet, when we return to the surface where our relationships and daily responsibilities await, we feel compelled to talk about it. That’s the paradox: trying to put into words what no words can qualify or contain.

Talking about something beyond words requires a form of language that can represent this mystery metaphorically. Even to speak of the experience as a “descent” across a “threshold” (or series of thresholds) into a deep “ground” is using language in a highly symbolic way. The experience is not literally this but nevertheless really is! Metaphors serve the purpose of “carrying across” (meta-phorein) into verbal intelligence something that doesn’t lend itself to objective thinking; it’s not even some thing.

Religion’s preferred vehicle for such metaphorical representation is myth, referring to a narrative plot (Greek mythos) that serves as the backbone of story. The picture language anchored to this action-line only seems ancillary to the cause-and-effect sequence of the story itself, when its true purpose is to pull awareness into contemplation of a timeless mystery behind it all. This is essentially no different from contemplating any other form of well-composed art: You begin by looking at it, but soon enough you are pulled through it and into the creative consciousness that brought it forth.

For a myth to make sense, at least at the surface level, the architecture of reality it assumes must be compatible with the cosmology of the times. Ancient cosmology envisioned the outer realm as arranged vertically, with distinct levels (typically three) connected by an axis passing through the center of a stationary earth. The action of gods, heroes, and saviors – again, acknowledged as metaphorical representations – naturally conformed to this “up and down” structure of reality.

Deities had to come down from heaven and go back up again. Heroes and saviors might descend to the underworld (in death or by some secret passage) and come back up (by resurrection or escape) with boons for their community. By the Christian era, the departed saved and the departed damned were imagined as “up” in heaven or “down” in hell, as the case may be.

By virtue of the vibrant connection between the inner realm of spirituality and the outer realm of cosmology, ancient religion was an active sponsor of our awareness of living in a “universe” – the turning-as-one of all things. Whereas the term cosmos simply refers to the “order” we can perceive around us, a true sense of the universe to which we belong reflects a mental integration of this order with the grounding mystery in which all things exist. In this way, an active appreciation of the universe is a product of spirituality (mystical union) and cosmology (surrounding order).

The outer realm is our context of life, the expanding environment in which we human beings need to locate ourselves. If we can detach the discipline of science from the peculiar tradition of Western science as we know it today, then even the three-story model that stood as background architecture to the ancient myths may be appreciated as “scientific,” as a theoretical explanation drawn from straightforward observations of the outer realm. Today, a myth of visitors from outer space is more compatible with our current cosmology, and hence more believable to the modern mind, than the up-and-down traffic that would have made sense back then.

And this is where things started slipping with religion, not too many centuries ago. As science pursued an updated cosmology based on newly invented observational instruments (e.g., the Greek astrolabe and European telescope) and mathematical calculations, the older myths couldn’t keep up. More accurately, as we can see in our own day, the belief systems that had gotten attached to those older myths didn’t want to keep up. Science was pulling the hearts and minds of people into a secular and godless age, undermining faith and threatening the eternal security of “doubting believers.”

What had for millenniums coordinated a meaningful dialogue between the inner and outer realms of human experience thus dug in its heels and held fast to an obsolete science, trading intellectual relevance for emotional conviction. And the stories? What became of the myths? Lacking a respectable cosmology to back them up, the only way to take myths seriously was to read them literally – as eye-witness accounts of supernatural and miraculous events. This required a bold division between other people’s myths and our salvation history, which New Testament authors were busy making already in the late first century CE (cf. 2 Peter 1:16).

Doubly tragic for religion was its aggressive campaign against spirituality, increasingly identified with “mysticism” and censored as godless self-absorption. Any teaching that encouraged an individual to surrender completely to union with the divine, understood as the non-objective presence and grounding mystery of being, was condemned out of hand as heresy, blasphemy, and atheism. Despite the fact that the major theistic traditions all contain subcurrents of spirituality which are clearly mystical in orientation, the mainstream ideologies (in pulpit and press) regard such practices with a high degree of suspicion.

However much the religions have failed in fulfilling their purpose (as religion), the need persists for human beings to meaningfully connect the inner and outer realms of experience. To whatever extent we can create new metaphors to carry our spiritual intuitions of the grounding mystery into a cosmology big enough to frame the stars, deep enough to appreciate our place in the evolution of life, and wise enough to use our considerable influence for the good of our planet and future generations – to that extent we will be healed, made whole, and rediscover the holiness of being alive.

Your brain is “wired” into your body through a complex nervous system that reaches out to your muscles, organs, glands, tissues and cells. I call this a braintract – specifically your lower braintract, since you have an upper one as well (which we’ll get to in a bit). With brain-imaging technology and carefully controlled experiments, neuroscience has discovered that your brain is constantly monitoring the stream of experience flowing below the threshold of conscious attention. This spontaneous engagement with the stream of experience is called intuition (or at least that’s what I’m calling it), and it’s where your brain is “picking up” all kinds of subtle impressions of what’s really going on.

Your brain is “wired” into your body through a complex nervous system that reaches out to your muscles, organs, glands, tissues and cells. I call this a braintract – specifically your lower braintract, since you have an upper one as well (which we’ll get to in a bit). With brain-imaging technology and carefully controlled experiments, neuroscience has discovered that your brain is constantly monitoring the stream of experience flowing below the threshold of conscious attention. This spontaneous engagement with the stream of experience is called intuition (or at least that’s what I’m calling it), and it’s where your brain is “picking up” all kinds of subtle impressions of what’s really going on.

As religion began to reconstruct itself around the death anxiety of the ego, traditional commitments of keeping communal life in rhythm with the cycles of nature were given up in favor of a program for saving the soul from the ravages of time – safe forever with god and other believers in heaven. This program not surprisingly included strong sanctions against “carnal” desire and the pursuit of pleasure for pleasure’s sake; such was the way of woman and the devil. The soul – which by now had become essentially synonymous with the ego personality – must be kept pure or “cleansed” of its attachment to the body through repression and ascetic practices.

As religion began to reconstruct itself around the death anxiety of the ego, traditional commitments of keeping communal life in rhythm with the cycles of nature were given up in favor of a program for saving the soul from the ravages of time – safe forever with god and other believers in heaven. This program not surprisingly included strong sanctions against “carnal” desire and the pursuit of pleasure for pleasure’s sake; such was the way of woman and the devil. The soul – which by now had become essentially synonymous with the ego personality – must be kept pure or “cleansed” of its attachment to the body through repression and ascetic practices.