What is the meaning of Easter?

Is it just about someone who died nearly two thousand years ago and came back to life? For almost half its history, Christianity celebrated Easter as its principal message to the world. As the Middle Ages dawned, however, the focus shifted to the Atonement where Jesus was supposed to have accomplished his world-saving work. Since then, Easter has been the ups y-daisy to Good Friday’s (only apparent) tragedy.

Just look at the difference in iconography between the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic (Latin) traditions. In the former, Jesus is risen, radiant, and very alive, while in the latter he hangs on his cross, gaunt, emaciated, and dead. And even though the Protestant churches replaced the Catholic crucifix with an empty cross, the centrality of Jesus’ sacrificial death continued into the Reformation. Consequently, the narrative of Easter has been interpreted as God’s “Yes” (on Sunday) to the world’s “No” (on Good Friday) – a great reversal where the humiliation of the cross was trumped by the glory of resurrection, ascension, and celestial coronation (as depicted in so much late-medieval and Renaissance art).

My frustration has to do with how this focus on Good Friday and Easter as events in the career of Jesus, while presumably benefiting the world by extension, keeps them back there in history and locked inside a literal Bible. Perhaps our invention of the literal Bible – of a Bible that must be taken literally – is more a political tactic designed to protect our possession of truth against competitors, heretics, and potential converts, than it is out of reverence for the Holy Question at the heart of existence which it seeks to answer across its pages.

Religion is not principally about the supernatural, immortality, or getting to heaven. It begins (or once began) in the realization that human existence is not entirely enclosed by nature and instinct, but stands rather as an open question that subsequently gets worked out (but never finally satisfied) in our quest for belonging, identity, and purpose. This open question calls to us from a beyond within ourselves and asks “Why am I here?” – the primitive and mystical origin of the later philosophical conundrum “Why is there something rather than nothing?”

Religion, then, is the more or less systematic way that this question of existence – this Holy Question – is answered. We call it holy because it has the character and feel of otherness, of addressing us from elsewhere. Perhaps because it is so relentless and restless, refusing to leave us alone, human beings universally have acknowledged it as “Thou.” Significantly, in our Bible the recurring word “repent” refers to a turn in response to being called.

Everything in religion, from its symbolism and mythology (sacred stories), to its rituals and devotional practices, is in effect an elaborate answer to this Holy Question of why I am here, why you are here, why are we here together. Where do we belong? How are we related? What are we here to do?

Even our theological construct of God as the supreme being who created the universe, watches over us, puts expectations on us and holds us accountable, is a projected personification of what human beings have believed to stand on the sending side of the Holy Question.

So when I contemplate the story of Easter, I want to listen for how it answers the question “Why am I here?” I won’t be distracted by the popular, and as I said, very modern assumption that the truth of the story is reducible to historical events – supernatural interventions and miracles purported to have happened long ago. There’s no need to trade our twenty-first century cosmology (theory of the universe) for the first-century cosmology assumed by the Gospel writers, where the up-and-down traffic between earth, heaven, and the underworld presented a perfectly acceptable plot for sacred story.

Since it’s not concerned with describing objective events, I don’t need to leave my intellect at the door before entering the imaginarium of myth.

With the Easter story, as in any sacred myth, we need to stay observant for those epiphanies at the surface where something more is being said or shown. Such locations are marked by images, metaphors, and archetypes that, as it were, pivot the axis of meaning from the horizontal plane of the narrative plot in order to engage deeper (or higher) dimensions. This is where we find an answer to the Holy Question, and if we stay engaged at this level, without allowing the metaphor to flatten out and lose its power, we stand a chance of being confronted and grasped by a profound truth.

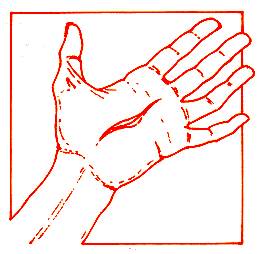

For me, there is one image in the Easter story that speaks in this way. It’s not the empty tomb or the angels or even the appearance of the risen Jesus to early morning visitors. Actually, it is an appearance of Jesus, but one that happens on Easter evening among the company of disciples who had closed themselves inside a locked room out of fear that the authorities might come looking for them next.

Only the Third and Fourth Gospels (Luke and John) include this epiphany – this archetypal answer to the Holy Question “Why am I here?” – so it either originated with Luke (who wrote earlier) and was adapted by John, or it was circulating in some early Christian source outside them both.

So there stands Jesus, probably in his skivvies or buck naked. (He had been stripped of his clothes while hanging on the cross, and, according to John, the linen cloths that some women had used in his funerary preparation on Friday evening were found neatly folded inside his burial cave Sunday morning.) “Relax, it’s okay” – or “Peace be with you,” he says to his friends. And then …

And then the risen Jesus holds out his hands and feet, bearing the wounds of crucifixion where spikes had been driven through into wood. (In John’s version he also shows them the gash in his side where a Roman spear had confirmed his death.) The wounds of a dead man borne in the body of a living man.

And then the risen Jesus holds out his hands and feet, bearing the wounds of crucifixion where spikes had been driven through into wood. (In John’s version he also shows them the gash in his side where a Roman spear had confirmed his death.) The wounds of a dead man borne in the body of a living man.

That’s the image, the answer to the Holy Question. It’s presented in the myth as an ironic metaphor, one that contains a contradiction (a living dead man) and holds open an irreconcilable paradox.

If Jesus is The Archetypal Man in early Christian mythology – and this is clearly the case as the apostle Paul pointed out many times in his writings (which predate the Gospels) – then in this particular story he is representing all of us; or more poignantly, each of us.

A human being is both subject to the gravity of existence and the bearer of its glory.

During his brief public ministry, Jesus had demonstrated deep compassion for those afflicted under the grind of abject poverty, chronic pain, spiritual emptiness, and political oppression. Instead of preaching to them of pie in the sky or training them in techniques of meditative detachment, he got down into their suffering with them and did what he could to help them out. (The stories of miracle healings, which all the Gospels employ in their portraits of Jesus, carry this memory of how Jesus stepped into the suffering of others with caring support and saved them from despair.)

In addition to taking on the human condition evident in the afflictions of others, Jesus was remembered by the way he accepted – but not merely in a passive mode; rather, how he embraced – his own mortality, especially with the growing prospect of a violent death on his horizon. His challenge to the disciples to “take up your cross,” even if the overt reference to crucifixion was a gloss added later by storytellers, expresses an understanding that commitment to human solidarity and liberation will likely land one in trouble with authorities.

And Rome loved its crosses.

In the face of death, Jesus didn’t back down. As the political and religious heat grew around his notoriety and it was clear there would be no way out, he remained steadfast and resolute in his vision of a world free of bigotry, dogmatism, violence, and fear. True enough, he died for his belief – but more importantly, for the way he demonstrated his belief in action.

Perhaps at first, in the period of time represented in the story as a sabbath of sorrow when all hope seemed lost, Jesus’ vision was regarded a failure.

At some point, however – and again, a three-day event cycle in the narrative probably conveys the meaning of complete transformation, as it still does in contemporary fiction and film – someone in the company of mourners remembered the character of their leader as one who had lived a compassionate, brave, and authentically human life. Upon reflection, he had shown them how to combine grace and courage, passion and humility, how to live like you’re dying.

This is where I think the Holy Question surfaced in the consciousness of Jesus’ bereaved disciples. “Why am I here?” The gravity and glory of human existence had been paradoxically revealed in Jesus, and the ironic metaphor of him standing there in their midst – a living dead man, a man who answered the Holy Question by living fully into his death – ignited their hearts and started a revolution.

Just before he leaves them, Jesus breathes on his disciples and says, “Receive the Holy Spirit. Now it’s your turn.”

That’s what Easter means to me.

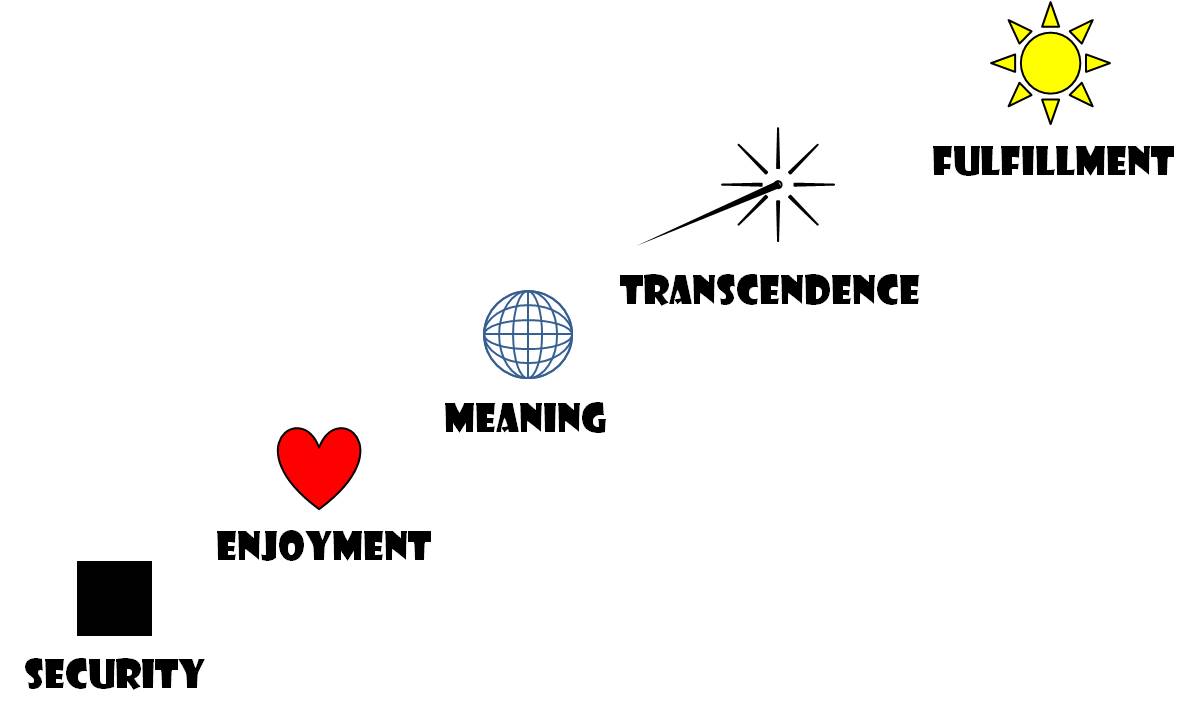

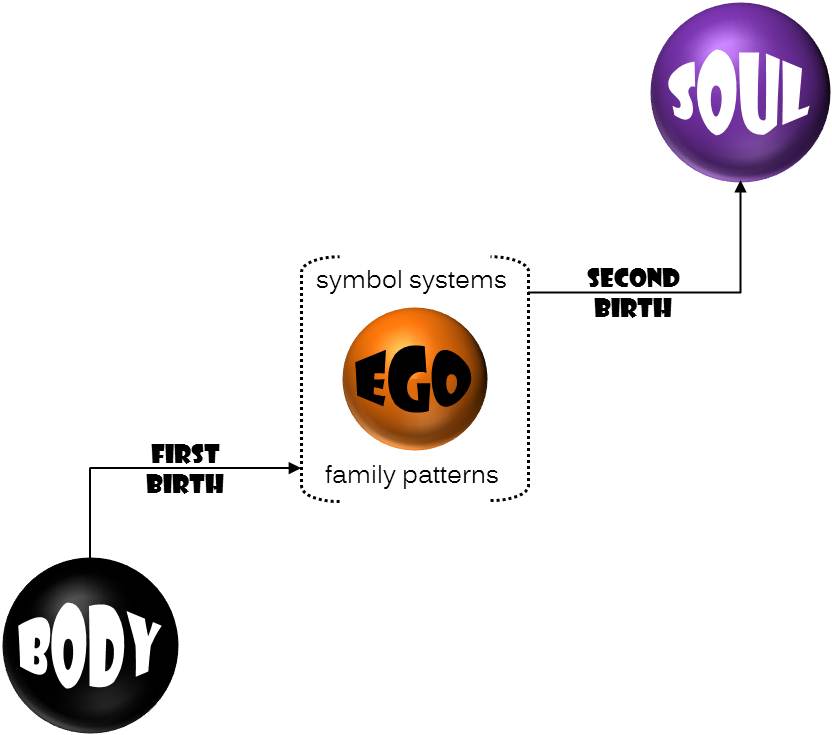

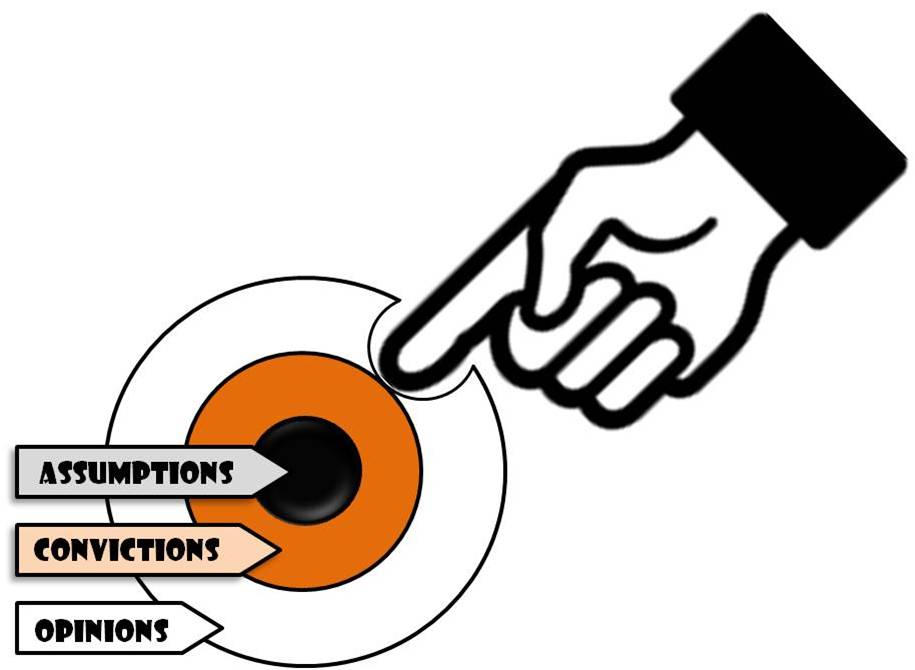

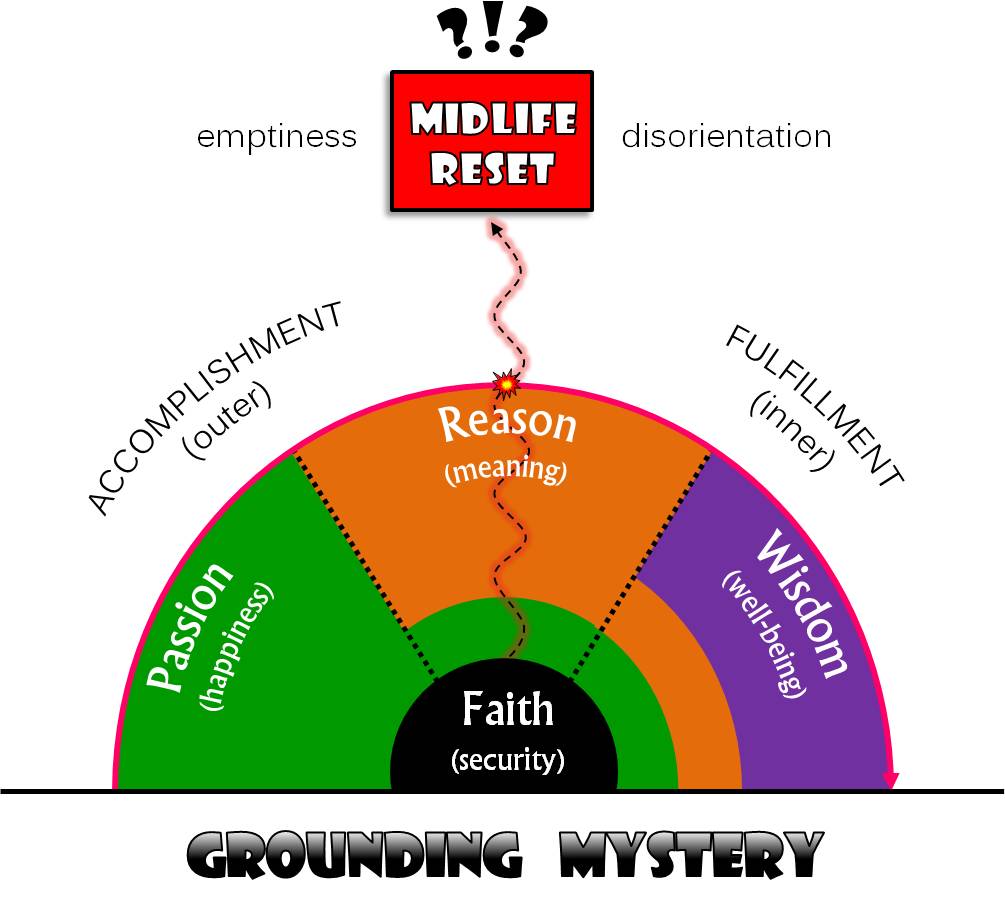

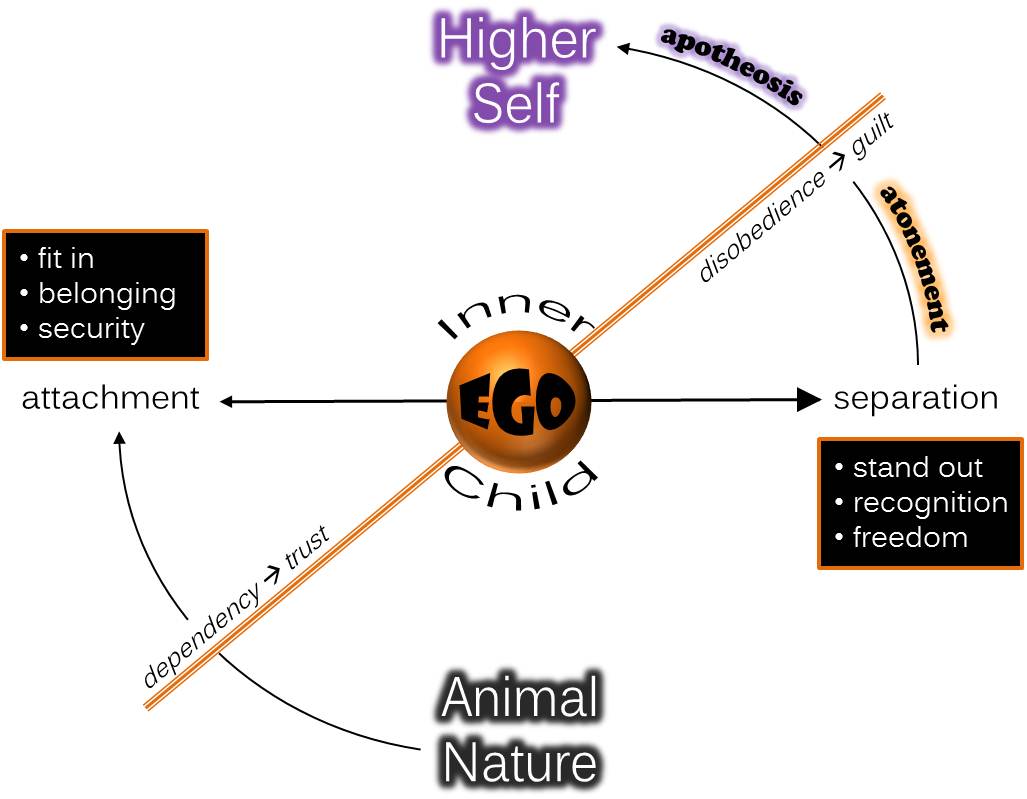

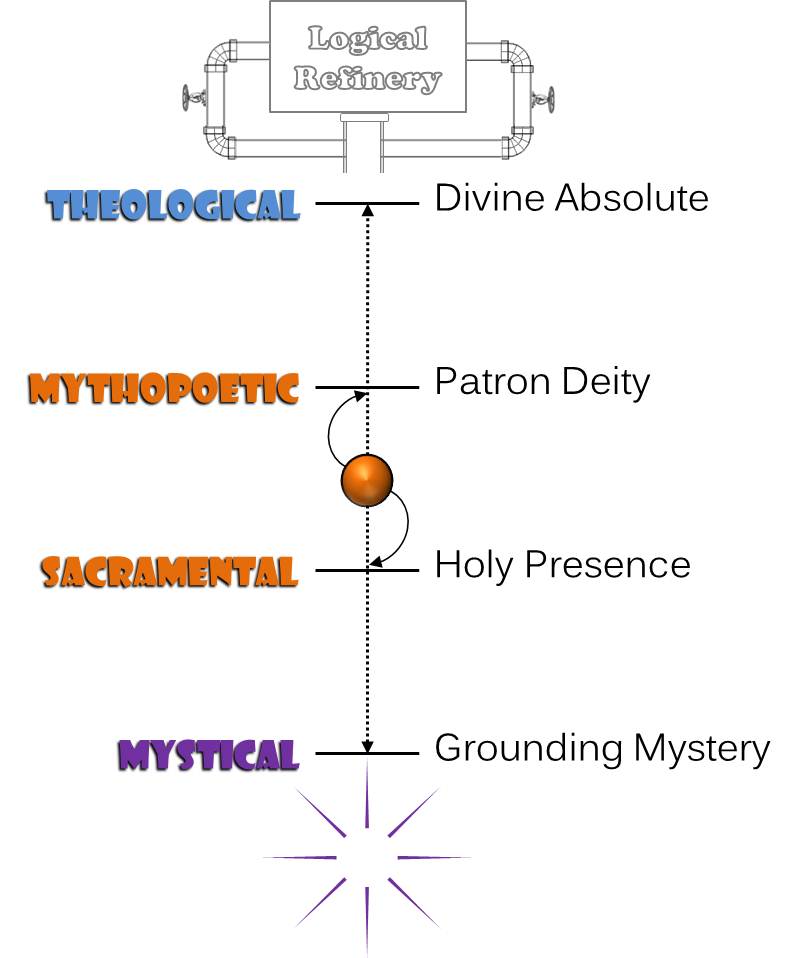

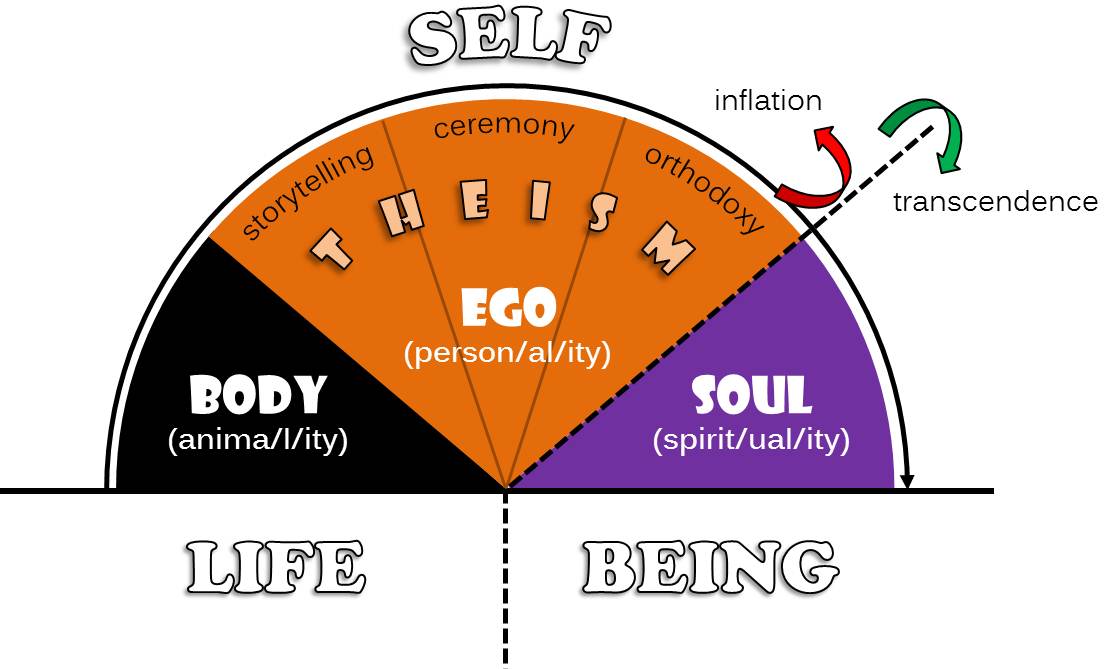

My diagram above illustrates the timing and sequence of human development as it tracks with the formation of ego consciousness. The arcing magenta-colored arrow represents the lifespan, which I’ve divided into four periods – the early life of a Child, followed by the age of Youth, maturing into a longer period of an Adult, and culminating in the late life of an Elder. Before I dig deeper into each of these four periods, let’s stay at this level of resolution and think about the major ideas carried in my diagram: Ground, Character, and Destiny.

My diagram above illustrates the timing and sequence of human development as it tracks with the formation of ego consciousness. The arcing magenta-colored arrow represents the lifespan, which I’ve divided into four periods – the early life of a Child, followed by the age of Youth, maturing into a longer period of an Adult, and culminating in the late life of an Elder. Before I dig deeper into each of these four periods, let’s stay at this level of resolution and think about the major ideas carried in my diagram: Ground, Character, and Destiny.