The representation of god in myth and belief has served three key functions over the long course of history: as (1) the hidden agency behind the forces and events of nature, (2) the transcendent legitimation of political authority, and as (3) the advancing ideal of our moral development as a species. In some cases, these three functions have been taken up into different deities, while in monotheism they were incorporated into a single supreme god.

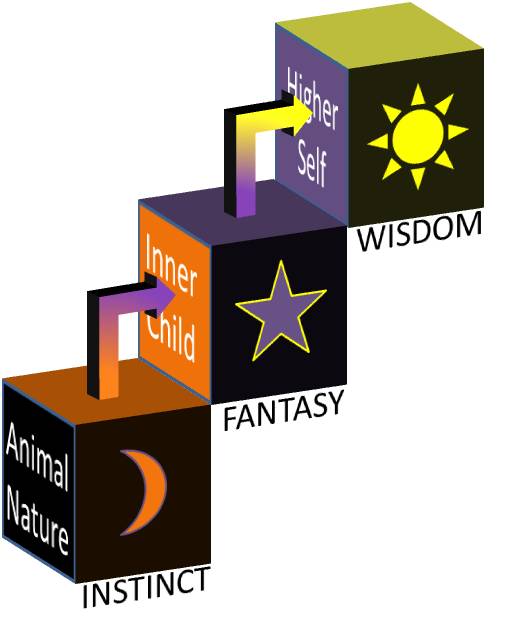

Since roughly the fifth century BCE, the West has been progressing through a series of cultural transformations, where each of these “functions of god” was taken over, absorbed, and transcended by the mythological god’s human creators. What was once projected outward – behind nature, above the throne, or ahead of our moral striving – was gradually and steadily internalized by the human spirit. With each step, our evolution has progressed into a new “post-theistic” era, relative to the function of god that has been rendered obsolete.

Early on, the gods of nature dissolved into physical laws, material forces, and mathematical formulations. Personified hidden agencies were no longer needed to explain weather events, the movement of planets, or the revolution of seasons. The rise of natural science pushed the Western experience into a post-theistic age, with respect to the mysteries of the cosmos.

It took longer for the political and moral frames to advance, however.

Kings, tyrants and despots continued to claim ordination by the gods, which partly explains why temple religion has received royal and state support for centuries – even to this day. Nevertheless, the rise of democracy began to take the power to rule away from the god and his monarch. A republican or constitutional form of government might still anchor its legitimacy in a vision of human nature as possessing certain inalienable rights endowed by the Creator, but responsibility for the political order is now firmly on our own shoulders.

The rise of science and democracy, then, marked two major transitions to post-theism in the West. Today we are on the progression threshold of a third shift, now focused on morality and what it means to be “good.”

No doubt, the democratic revolution – first in Athens, then later in Philadelphia – compelled this ethical shift, since the king’s order or a denominational moral code has less warrant when the divine authority once believed to stand behind it is no longer taken literally.

But one key moment in this transformation came with the teachings of Jesus.

The prophets of Israel – particularly Amos, Hosea, Micah and Isaiah – had already dared to internalize the voice of god and speak not just for him, but as him:

21 I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

22 Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

23 Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

24 But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream. (Amos 5)

No longer the priests, who were religious insiders of temple/throne religion, but outsiders (some ex-priests) took on the challenge of redefining traditional standards of moral obedience, righteousness, justice and compassion. By standing in god’s place and exhorting the people to stretch out for higher truth and a wider (more inclusive) love, the prophets prepared the way for Jesus.

Like no one before him or since, Jesus somehow had the audacity to not only redefine god’s will but his very identity. The deity who had been identified with holiness, separateness, vengeance and retribution was made-over into a “prodigal god” – wastefully kind, benevolent, compassionate, and forgiving. This last virtue particularly, forgiveness, was radically deconstructed by Jesus.

In his life and teaching, forgiveness – also known as loving your enemy – became a gracious and unconditional initiative, and not just a considerate response to repentance. As a proactive virtue of love, forgiveness could become a redemptive force inside the individual, between enemies, and across the world. To get there, the old god of morality who still operated according to the logic of retribution (“you get what you deserve”) needed to be absorbed and then transcended. Jesus was so bold as to invite his disciples to outdo god by forgiving without even the expectation of repentance.

In the ensuing decades after Jesus, some of his fans and followers grasped the radical nature of what he had done. By constructing a myth about his resurrection, his ascension into identification with god, and then descending as spirit one last time to become incarnate in the community carrying on in his name, the early Christians fulfilled his vision and ushered in the last great post-theistic age.

With the prophets and later Jesus, the Western trajectory of human evolution (by co-opting the near-eastern influence of Jewish history) had internalized and gone beyond the moral ideal of god. Now such advanced virtues as universal compassion and unconditional forgiveness were not just represented and glorified in Christian worship as “the god of Jesus Christ,” but they were expected to be embodied and lived out on the ground of daily life as well.

This quick review of post-theism as it progressed through the cultures of Greece and Israel should clarify where it is different from the quasi-philosophical position of atheism. While atheism is energized by its opposing stance relative to theism (“no” to its “yes”), post-theism involves not a refutation of god but rather his assimilation by the human being.

Imagined, composed, projected, glorified, obeyed, emulated, internalized and finally transcended – thus god is not so much displaced by natural science, liberal democracy and a radical ethic, as taken over and his “functions” assumed by his original creators.

For this reason, post-theism does not bother with lampooning religion or engaging in sacrilegious irreverence. It has no interest in exposing belief in god as weak-minded and childish – although it has an obligation (we might say, in the “spirit of Jesus”) to address and resolve the tendencies in religion toward dogmatism, bigotry, repression and violence.

Essentially, post-theism understands god differently than atheism. Our human representations of god are products of our own curiosity, speculation, creative imagination and spiritual insight. Even though we once needed to regard them as objectively real, we can now appreciate this need as a critical phase in the longer advancement of humanity into a way of life increasingly more grounded and responsible, more caring and inclusive, more daring and authentic.

One other important difference: in its evolutionary view of religion, post-theism affirms belief in god as developmentally appropriate. Until an individual is ready to “take god back,” an external deity provides the necessary security and support, confidence and inspiration, to both relax in faith and reach out into a higher purpose.

The historical progress of the larger culture must be repeated and fulfilled in each living generation.