It’s interesting how the evolution of life, the development of a species, and the maturation of individuals within a species all tend to proceed from simpler to more complex forms and stages of existence. The human embryo carries vestigial gills and a tail from our prehuman ancestors. In a not entirely dissimilar fashion, children grow into mental abilities following the same sequence as our species over many thousands of years. What we see at one level (life, species, individual) is evident in the other levels as well.

Culture is the construction zone where the degree of advancement in our human species gets transmitted from individual-level breakthroughs, into the collective consciousness of society, and back again to the individual in the form of innovations in the traditional way of life.

In the interest of social cohesion and stability, a preferred path of change would be able to keep some of what has been (as tradition), as it moves forward into what will be. The role of institutions can be understood in this sense, as conservative and stabilizing structures in the flow of cultural change. The very definition of religion, from the Latin religare meaning “to connect or tie back,” identifies it as an institution in this sense – indeed as the conservative and stabilizing structure in culture.

When the European Enlightenment got the intelligentsia excited about the possibility of throwing off the superstitions of the past to embrace a future of science, religion was the obvious and easy target. Without a doubt, there was much about the institution of Christendom that wouldn’t listen and constructively respond to new discoveries and developments going on at the ground level of human experience.

As the official Church condemned new theories and excommunicated the brave souls who dared contradict its now-archaic orthodoxy, the best (and perhaps the only) recourse for many was to simply push the whole outfit into the ditch and move on with progress. The modern West turned its attention to factual evidence and the technical possibilities of this world, content to leave spirituality, religion, and God Above in an early chapter of its new autobiography: The Enlightened Man’s Emancipation from Ignorance and Myth.

The Christianity we all know (and fewer of us love) is a type of religion known as theism, for the way it is oriented on and organized around the belief in a supreme being who is large and in charge. Our fortunate birth and prosperity in this life, followed (hopefully, if we get it right) by beatitude in the hereafter, is our Pilgrim’s Progress supervised by God Above.

We happen to be living in the twilight of theism, during a late phase known as orthodoxy. At this point it is primarily about believing the right things, and doing whatever it takes to defend and propagate “the one true faith” around the world. By now, for a large majority of Christian true believers, the present mystery (we can even call it the real presence) of God has receded permanently behind something much more pressing and important – and manageable: the right opinion (ortho+doxa) about God.

At the end of the day it’s all a very heady enterprise and increasingly irrelevant to everyday life. People are leaving the Church in droves, with the Enlightenment campaign of atheism once again on the rise. As a counter-measure, the engines of orthodoxy are locking into gear and plowing full steam ahead, until Jesus comes again or all hell breaks loose (rumor has it these might be the same event).

Fundamentalists, ultra-conservatives, and right-wing evangelicals are certainly not helping their cause, as bright and reasonable people who continue their quest for a grounded, connected, and personally relevant spiritual life are leaving the crazies to their end-game.

I spend more time than I would like trying to explain how the impulse to cast theism out with the dirty bathwater of dogmatic and dysfunctional religion, while certainly understandable to some extent, is not the real solution to our problem. For one thing, the theistic paradigm and its role in society should not be simply identified with any of its historical incarnations.

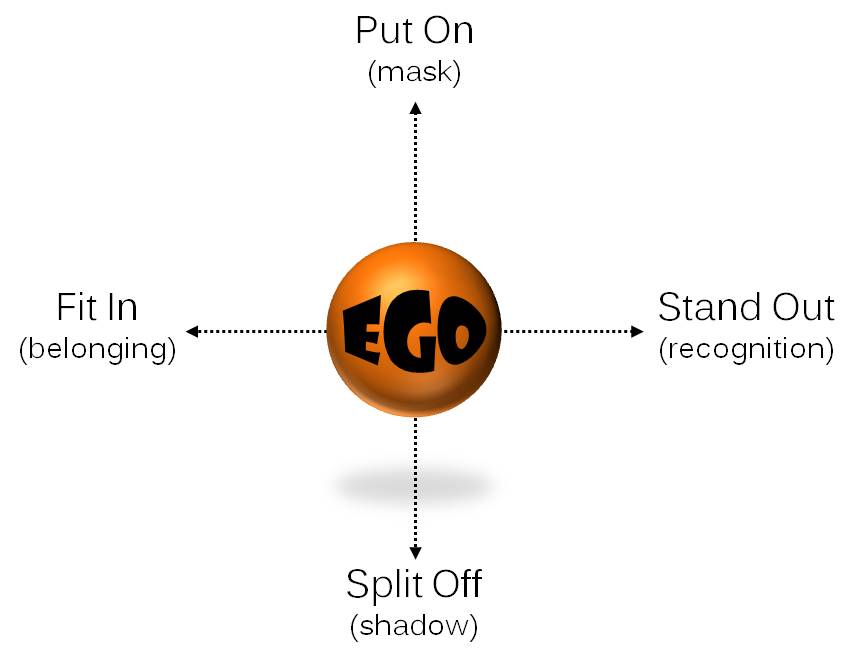

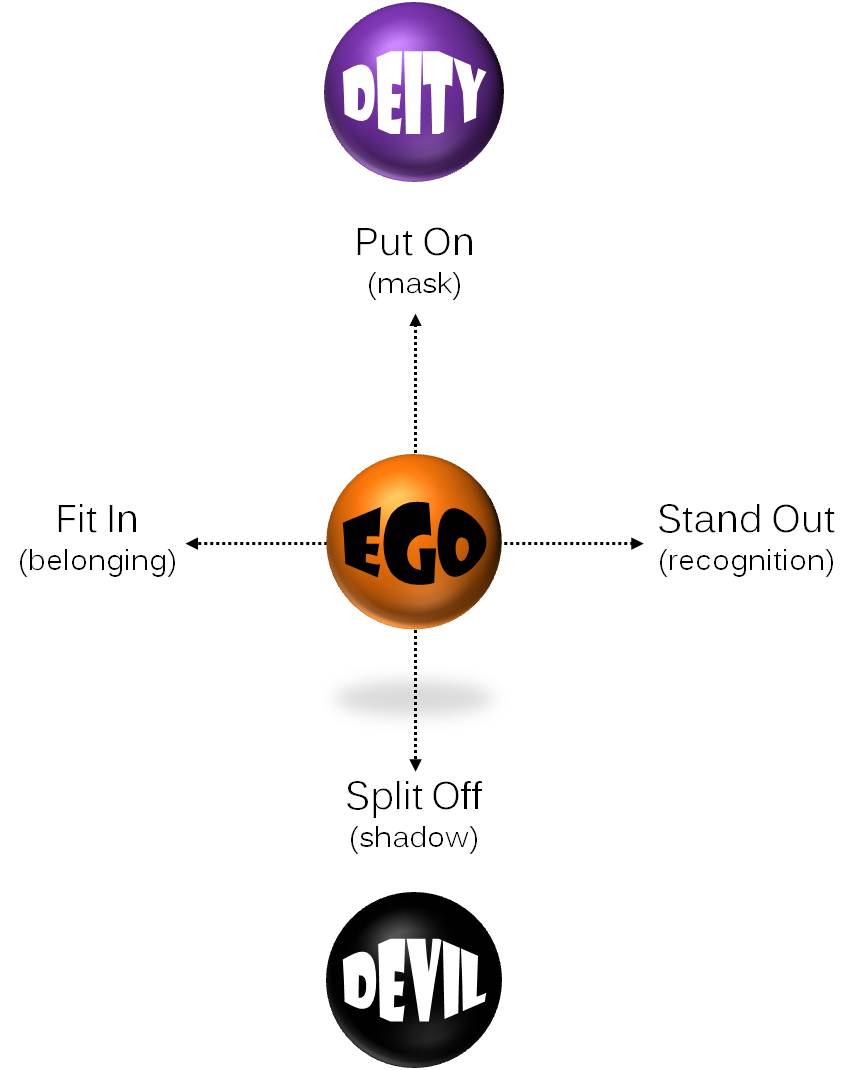

In other words, a corrupt version of theism is not necessarily a reason to reject theism itself outright. It happens that every institution is prone to desperate measures when threatened by the natural course of change. In this way, an institution is the cultural equivalent of an individual ego – a conservative and stabilizing construct of identity that resists becoming what it isn’t used to being.

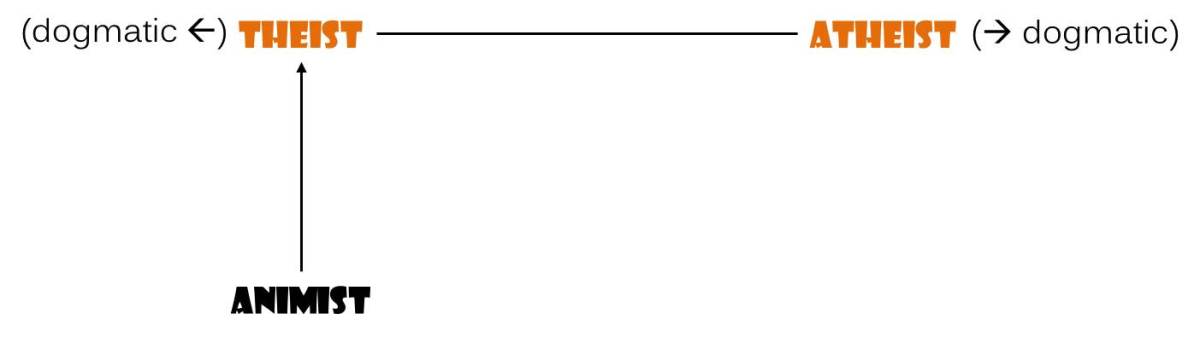

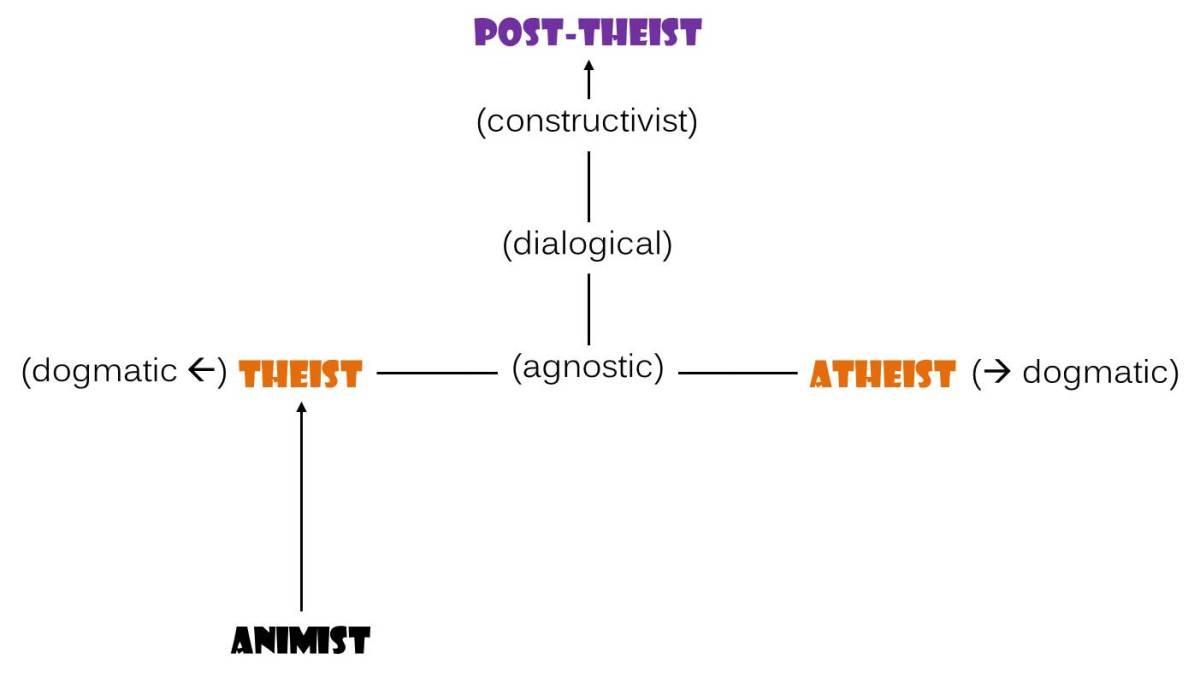

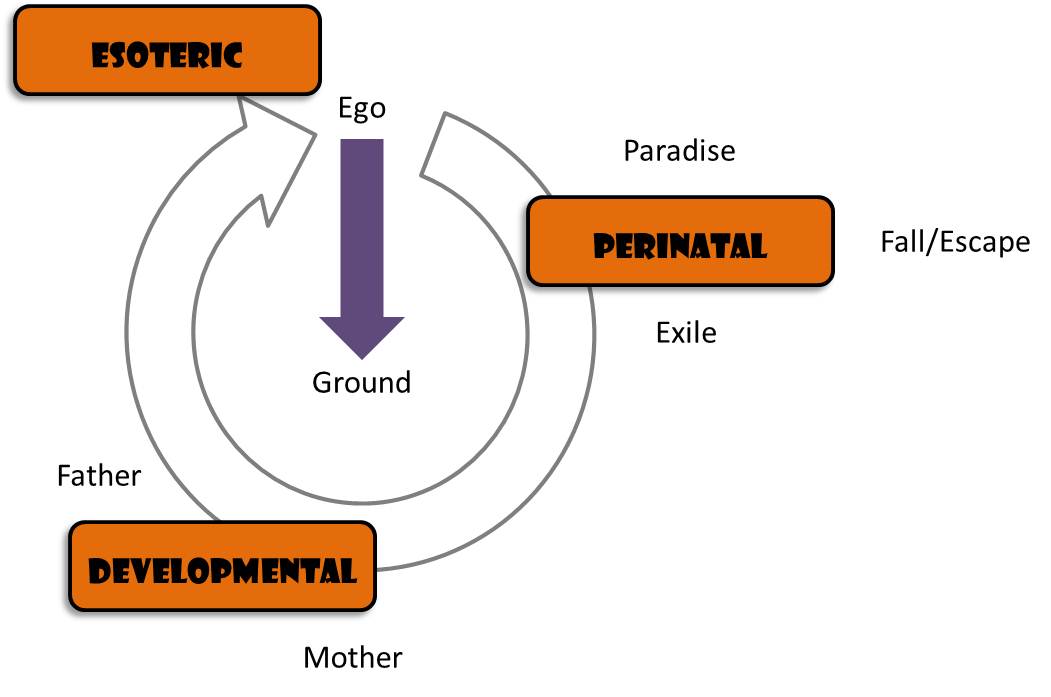

What follows is a perspective on theistic religion, exploring its development through distinct phases starting with its rise out of animism and following through its twilight into post-theistic forms of spirituality. My model for this developmental schema is not only based in the evidence of archaeology, but, just as important and even more useful, on the phases stretching from early childhood to maturity in the living individual today.

Earliest theism, just like early childhood, was lived in a world constructed of stories. There was no obvious boundary separating “fact” from “fiction,” the given facts of reality from the make-believe of fantasy. Theism was born in mythology (from the Greek mythos referring to a narrative plot, which is the structural arch that serves as the unifying spine of a story).

Earliest theism, just like early childhood, was lived in a world constructed of stories. There was no obvious boundary separating “fact” from “fiction,” the given facts of reality from the make-believe of fantasy. Theism was born in mythology (from the Greek mythos referring to a narrative plot, which is the structural arch that serves as the unifying spine of a story).

Its gods began as literary figures personifying the causal agencies behind the order and change of the sensory-physical realm. Myths were not regarded as explanations of reality (as a kind of primitive science), but instead were performances of meaning that conjured the gods into being with each rendition.

It’s difficult to appreciate or understand this phenomenon as we try to grasp it with adult minds, but perhaps you can remember how it was for you back then. The fantasy world of myth doesn’t merely fade into the metaphysical background when the story concludes. Rather, that world exists only in the myth and is called into expression every time the myth is performed afresh.

We modern adults entertain a delusion which assumes the persistence of reality in the way we imagine it to be, even when our stories (at this later stage known as theories) aren’t actively spinning in our minds. The paradigm-stretching frontier of quantum physics is confirming how mistaken this assumption is, and how much we really understood (though perhaps not consciously) as children.

At some point in late childhood and early adolescence the individual recognizes that real life requires an adjustment from imaginary friends, magical time warps, and free-spirited performances of backyard fantasy, to the daily grind of household chores and lesson plans.

A more complex and complicated social experience means that opportunities for reigniting the creative imagination must be “staged,” that is, relegated to a consecrated time and location that will be relatively free of interruptions. Here, in this sacred space, the stories will be recited; but in view of limited time, only the major scenes and signature events are called to mind.

The required investment of time, attention, and energy in social responsibilities will not return the degree of enchantment and inspiration an individual needs to be happy. There needs to be a place for mythic performance and reconnecting with the grounding mystery. Besides, the mythological god can’t be left hanging in suspended narrative when it’s time to get back to the grindstone.

Theism had to adapt along with this emerging division between sacred and secular (temporal, daily) concerns. It did this by creating a special precinct where the majority could enter and observe an ordained minority dress up, recite the stories, and enact mythic events linking their broken time (divided and parsed out among countless duties) back to the deep time of an eternal (timeless) life.

Just as the holy precinct of ceremony served to connect a profane existence “outside the temple” (Latin profanus) to the sacred stories that weaved a tapestry of higher meaning, the god who originally lived in those stories was relocated to a supernatural realm overhead, standing by and watching over the business below. Even if the stories weren’t actively spinning, people could take comfort in knowing (technically believing) that he was in his place and doing his job.

On a designated day the community gathered in the temple, and at just the right moment an official would sound a bell, light a candle, unveil an icon, or recite a scripted prayer invoking (calling in) the presence of the god. At that very moment, all were in agreement (at least those paying attention) that the deity would descend from his abode in heaven and receive their worship.

A ritual enactment of sacred story would typically culminate at a point where the congregation was invited to step into deep time once again. Afterwards a signal was given bringing the ceremony to an end, and the people would depart to their workaday worlds.

With a growing population and the inevitable pluralism that comes with it, getting to the chapel on time becomes more of a challenge for a lot of people. How can theism survive when the ceremonies and sacred performances start losing attendance? What happens when god above no longer has an official invitation to condescend to the supplications of his gathered assembly of devotees?

This is what happens: former true believers give up their denominational affiliation and do their best to continue on their own. They will still look up when they speak of god, point to heaven and cross themselves when they score a goal, and perhaps bow their heads and say a prayer before breakfast.

Once in a while they might make their way back to the chapel (maybe on time) to observe a performance of one of the really big stories. As they watch, a dim memory of childhood enchantment will stir somewhere deep inside them and they will feel the magic once more.

How can theism hold on when its ceremonial system – the land and buildings, the gold-plated symbols and silken vestments, the professional staff of ordained ministers, and the hard-won market share of rapidly defecting souls – is sliding into obsolescence and bankruptcy? The answer brings us to the third and final phase in the lifespan of theism, the twilight of institutionalized religion known as orthodoxy.

The enchanted storytelling of early childhood gives way to staged ceremony in young adulthood, which in turn and with further reduction eventually gets packaged up into neat boxes of truth called doctrines. An obvious advantage of this reduction of theism to doctrines lies in its handy portability, in the way it can be carried conveniently inside the head and transferred into more heads by rote memorization and Sunday School curricula.

If the first phase of theism (storytelling) featured the bard, and the second phase (ceremony) depended on the mediation of priests, this third phase (orthodoxy) belongs to the theologians. They are the experts who tell us what to believe about god and other metaphysical things.

Since theism at this point has become a rather sophisticated set of beliefs, the best (and perhaps only) way to impress their importance on its members is to make the doctrines necessary to what more and more people are lacking and so desperately looking for: security and longevity – specifically that odd fusion of security and longevity defined in the doctrine of everlasting life.

As time goes on, this notion of a future escape from a life burdened by fatigue, boredom, and absurdity grows more attractive, until the true believer is willing to give up everything – or, if necessary, to destroy everything – for its sake.

In the Age of Orthodoxy people still speak of the god above, of the miracles of long ago, or of a coming apocalypse and future rapture of the saints, but you’ll notice that the critical point of reference is consistently outside the present world. Celebrity hucksters and pulpiteers try to fill the vacuum with staged demonstrations of “faith healing” and prophetic clairvoyance, but the inspiration is cheap and unsatisfying. Mega-churches and sports stadiums become personality cults centered on the success, charisma, theatrics, and alluring ideal of their alpha leaders.

In a sense, this transformation of old-style sermon auditions into entertaining religious theater represents a final attempt of theism to push back the coming night. There’s no getting around the fact that orthodoxy just isn’t that interesting, and as it rapidly loses currency in the marketplace of relevant concerns, more and more people are saying good-bye to church, to organized religion and its god-in-a-box.

As a cultural transition, the crossover from managed religion to something more experiential and inwardly grounded corresponds to that phase for the individual, when a deeper thirst for life in its fullness forces him or her to push back from the table of conventional orthodoxy and its bland concoction of spiritual sedatives.

In the twilight of theism, people are starting to give voice to their doubts, but also, increasingly, to their questions, their long-buried intuitions, and their rising new-world aspirations. They want more than anything to be real, to be fully present, and deeply engaged in life with creative authority.

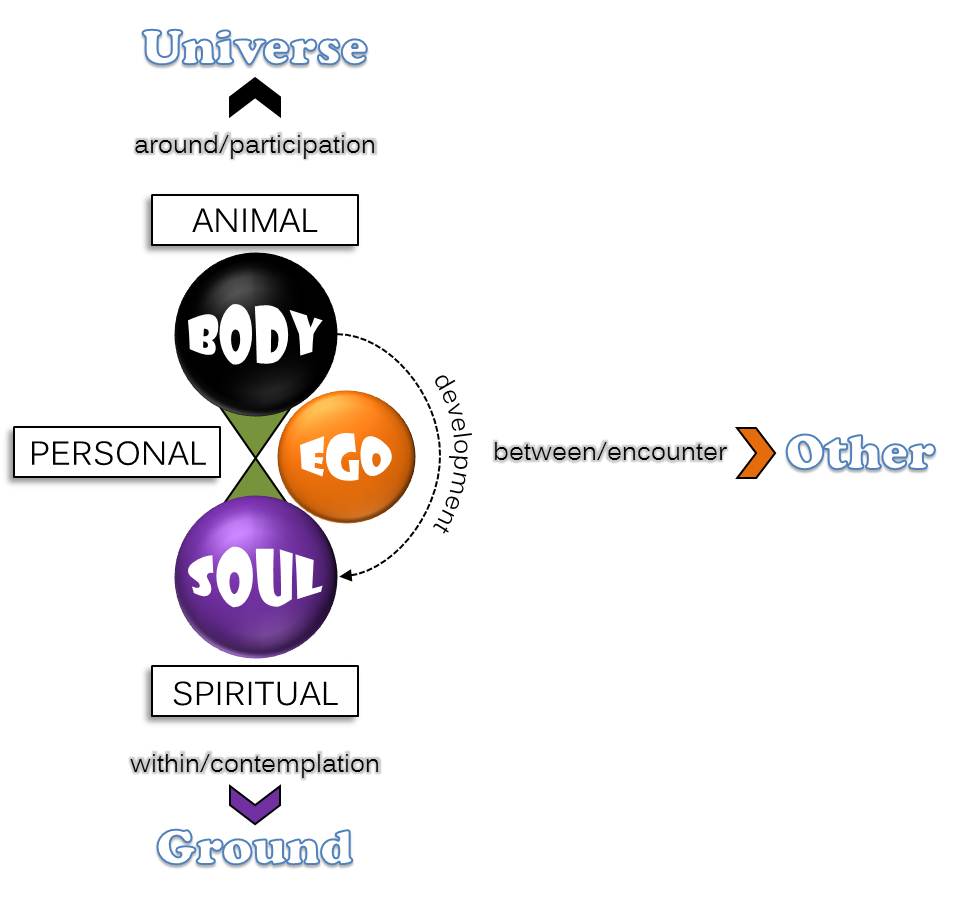

This inward turn is the critical move of post-theism. It’s not about pulling down orthodoxy or refuting its god, but rather simply letting go and quietly sinking into being. Quietly is a reminder that words at this point are like hooks that can snag and slow one’s descent, running the risk of turning even this into another religion with its own esoteric orthodoxy.

The ego and its constructed word-world of meaning need to be left behind so that consciousness can softly settle into the still center of contemplative awareness. Here all is one. There is only this.

Here is born (or reborn) that singular insight which inspired us to tell stories in the first place. Now, perhaps, with a lifetime of experience and some wisdom in our bones, we can tell new stories.

It’s always been and will always be here and now.

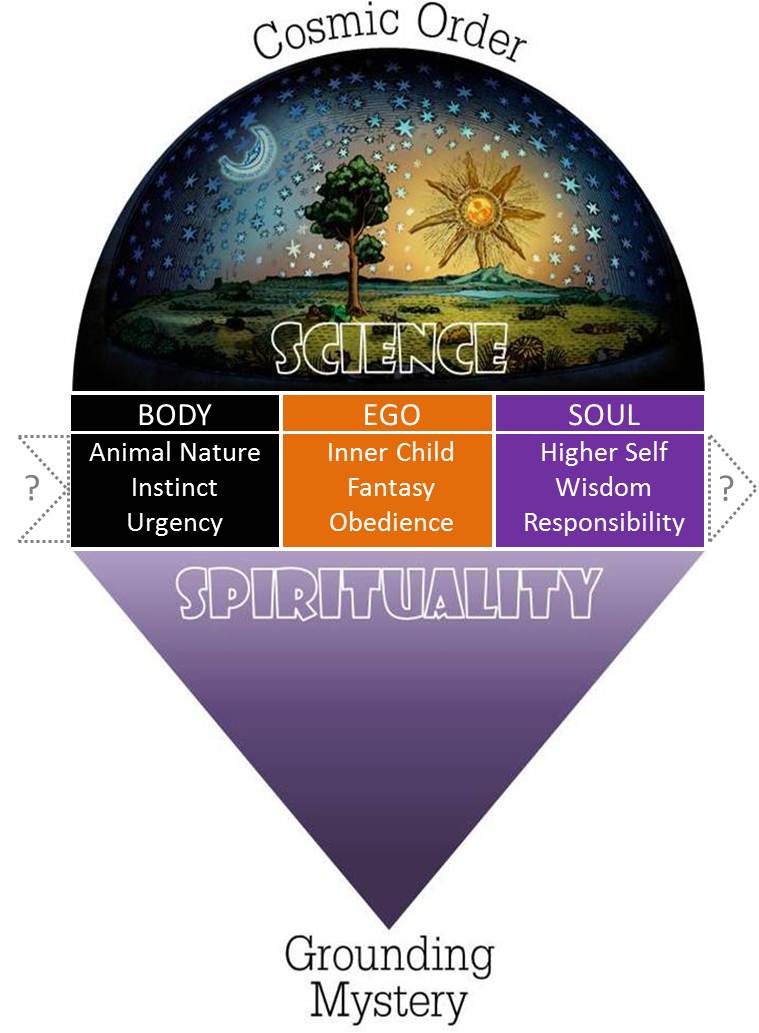

Religion began in the body, where the visceral urgencies of our animal life resonate with and link into (religare means to connect) the rhythms of nature. Earliest religion was animistic, preoccupied with the provident support of reality and the life-force that ebbs and flows along the rhythmic cycles of natural time. The pressing concern was to live in accord with these cycles, to flourish in the fertile grooves of dependency and to celebrate the mystery, both tremendous and fascinating (Rudolph Otto’s mysterium tremendum et fascinans), in which we exist.

Religion began in the body, where the visceral urgencies of our animal life resonate with and link into (religare means to connect) the rhythms of nature. Earliest religion was animistic, preoccupied with the provident support of reality and the life-force that ebbs and flows along the rhythmic cycles of natural time. The pressing concern was to live in accord with these cycles, to flourish in the fertile grooves of dependency and to celebrate the mystery, both tremendous and fascinating (Rudolph Otto’s mysterium tremendum et fascinans), in which we exist.