As a proponent of the type of religion known as post-theism, I have devoted a large number of posts in this blog to its proper definition. We shouldn’t think of post-theism as either Atheism or Theism 2.0, since its principal concern is not with the objective existence of god but rather the liberated life “after” (post-), or on the other side of, god.

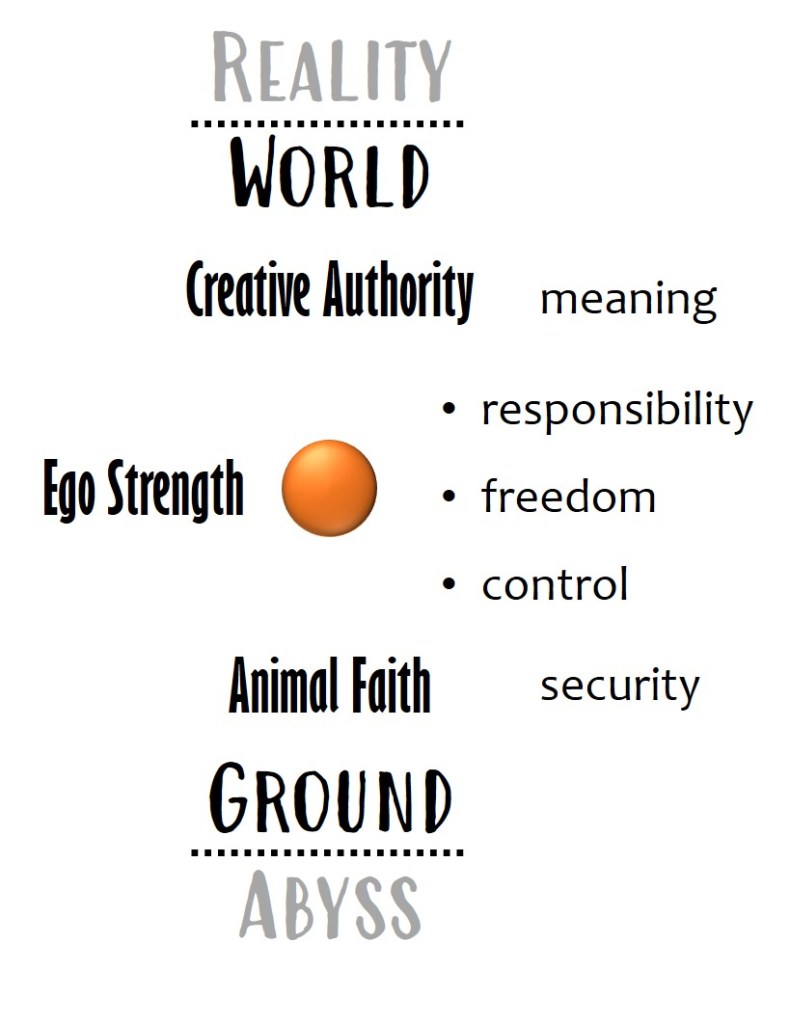

Post-theism affirms god’s central position through the middle stages in the sequence of faith development (from the research of James Fowler, these are the stages of mythic-literal, synthetic-conventional, and individuative-reflective faith). But it regards this god as a mythopoetic metaphor of the Present Mystery of Reality, of the Ground of Being or being-itself, and not a being separate and apart from us.

This seeming denial of god’s objective existence has gotten post-theism labeled and dismissed as just another updated (2.0) version of atheism, when it is really unconcerned with the question of god’s existence but seeks rather to interpret the meaning of god in relation to the evolution of spirituality and faith development.

In fact, an insistence on the priority of god’s metaphorical meaning over god’s objective existence is not a denial but a necessary realignment of god as symbol.

Ever since the first mythmakers, humans have known that God (uppercase G: the Present Mystery) is within us – as well as between, among, all around, and beyond us. The gods (lowercase g: mythopoetic metaphors of God) were intended and understood as imaginated, personified, and fictional representations of this essential-universal Mystery.

No human ever encountered these beings in the real world (i.e., Reality) – nor did they expect to. That is, until theism lost its focus and styled itself the defender of god’s existence against the rising wave of empirical science and secular humanism.

Regardless, a direct encounter with god has remained only an expectation, conveniently postponed until after death when the believer anticipates seeing god on his throne in heaven.

From that moment onwards, theistic religion became increasingly regressive, otherworldly, and irrelevant. The focus of piety shifted more to repetition compulsions like cross-referencing Bible studies, reciting creeds with the standing congregation, and participating in ritual commemorations of biblical scenes from long ago.

Post-theism comes about either by the normal course of faith development, or through crisis and confusion generated inside the insulated echo chamber of theism. It is fully accepting of the prospect of living in the theistic environment of symbols, stories, sacraments, and sanctuaries – as long as these are appreciated for their transparency to the Mystery within, between, among, around and beyond, and not allowed to become idols in its place.

As I see it, post-theism would ideally find a hospitable and symbol-rich habitat in theism, serving to keep its role-play game honest and properly grounded.

My own experience as a professional pastor in a conservative mainline Protestant tradition of Christian theism for 15 years confirmed a general openness to the Mystery, with a correlated interest in looking through god to the Present Mystery (or real Presence) of God, beyond names and forms.

Unfortunately, while I enjoyed some freedom to explore this Mystery with members of my congregation, our denomination was already closing down around its confessional standards of orthodoxy and against the larger environmental forces of pluralism, secularism, and globalism which had been challenging the tradition for decades to meet this new reality with a relevant spirituality and faith.

This helped me appreciate post-theism in a new light: as not just another stage in the development of religion, but as a renaissance-in-waiting inside theism for the time when conditions are right for it to awaken.

As long as theism maintains its protected membership of believers, the insights of a post-theistic spirituality may surface only intermittently in private devotion and small group discussions. Theistic ideology can sample and digest only small doses at a time, however, which allows it to recover its orthodox composure between such excursions into the Present Mystery.

When the number of waking post-theists reaches critical mass, a more formal censure and discipline may be in order. And when that conspiracy of pluralism, secularism, and globalism outside the doors confronts the tribal morality with its diversity of values, views, and ways of life, conditions are primed for a major transformation.

This very concurrent crisis of internal breakthroughs and external break-ins has erupted in episodes of post-theistic renaissance throughout the history of higher culture.

Jeremiah, Siddhartha, Mencius, Jesus, al-Ḥallāj, Johannes (“Meister”) Eckhart, Martin Luther, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Paul Tillich, and Martin Luther King, Jr. (among many others) charted new frontiers in post-theistic spirituality. Whether by the mystical-inward or ethical-outward path, each challenged his fellow believers and an entire generation to drop beneath or go beyond their tribal gods for an experience of the Present Mystery of Reality.

All of them refused to take the gods of their traditions literally, but instead they broke with tradition – or rather sought to break their traditions open – to a deeper (mystical) and larger (ethical) concept of God.

For the Second Temple Jewish tradition of early Roman times, it was Jesus who challenged his contemporary Jews to find God – what he called the power or kingdom of God – outside both the Temple precincts and their Hebrew lineage, as well as in the reality under their very feet, like a buried treasure (cf Matthew 13:44).

Because the entire Temple structure was designed on the idea that God (imaginated in the Hebrew god, Yahweh) stands apart from humans and must be satisfied with sacrifices before he can forgive sins, Jesus’ gospel (“good news”) of God’s unconditional forgiveness and radical inclusion of all people in holy community was rightfully regarded as a threat to Jewish identity and religion.

The early Christian movement was born out of this post-theistic vision of Jesus, picking up his insight to the point of identifying love as the very heart and essence of God (1 John 4:16). Although it was the ecclesiastical organization and political mission of the institutionalized Church that would soon enough spread Christianity so effectively around the globe, it was this post-theistic renaissance ignited by the life, message, and ministry of Jesus that got the whole thing going.

But just that quickly, Jesus’ vision faded from the Christian religion, behind the shutters and locks of a protected membership.

Many Christians today who are post-theistic in their spirituality, mystically grounded and ethically committed to the work of genuine community, have left the Church or were excommunicated because their faith (Fowler: conjunctive and universalizing) didn’t fit inside the boxes of Christian orthodoxy.

Others remain inside, finding their theology enriched by a fresh infusion of Mystery, nurturing the growth and progress of faith in their fellow believers as opportunities arise.

They are looking for, finding, or forming their own communities – I call them “Wisdom Circles” – where the Mystery of God and the meaning of god, the liberated life and a more perfect union, are explored in creative dialogue together.