Our present era of “fake news” has introduced the American public to a key premise of constructivism, which is that meaning is constructed by human minds and always perspective-dependent. What we call “news” is someone’s perspective on what happened and what it means. Until now we have counted on the news media to tell us the truth, thinking they are giving us “just the facts.”

Our present era of “fake news” has introduced the American public to a key premise of constructivism, which is that meaning is constructed by human minds and always perspective-dependent. What we call “news” is someone’s perspective on what happened and what it means. Until now we have counted on the news media to tell us the truth, thinking they are giving us “just the facts.”

But there are no plain facts, only data that have been selected from the ambiguous “data cloud” of reality. Our authorities are those who hold the rights of authorship and tell the rest of us stories of what it all means. If authority is power, then this power is a function of how convincing or inspiring an author’s story is, how effectively it influences the belief and behavior of others.

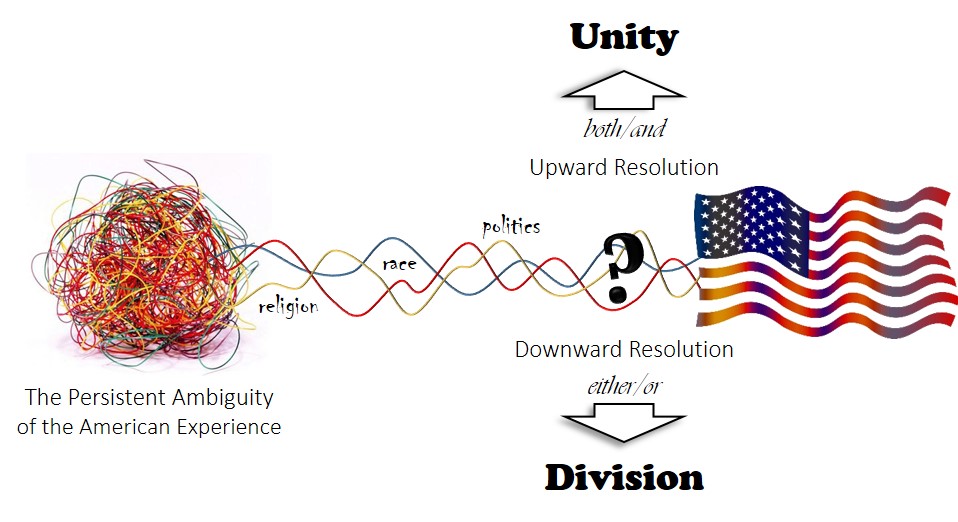

Just now we’re starting to understand the extent in which fact selection, taking perspective, and constructing meaning are determined by a deeper belief regarding the persistent ambiguity of what’s really going on.

Actually this deeper belief is energized by a need to resolve the ambiguity so it can be made to mean something. What I’m calling the “persistent ambiguity” of reality is profoundly intolerable to our minds, which work continuously to turn it into stories that make sense. Stories frame a context, make connections, establish causality, assign responsibility, attach value, and reveal a purpose (or likely consequence) that motivates us to choose a path and take action.

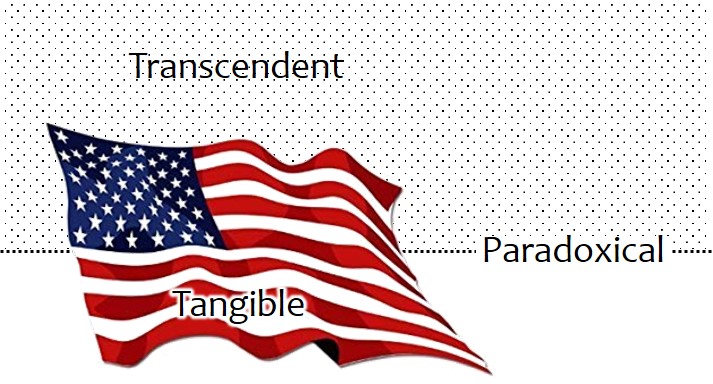

The resolution of ambiguity breaks in either of two directions: downward to (either/or) division or upward to (both/and) unity.

Once the divisions are made – and remember, these are based on narrative constructs of difference – the battlefront is suddenly obvious to us and we are compelled to choose a side. Below the grey ambiguity is where we find the diametrical opposites of “this OR that.” There is no room for compromise, and one side must win over (or be better than) the other.

Above the ambiguity is not simply more grey, but “this AND that” – not differences homogenized but mutually engaged in partnership. An upward resolution in unity means that distinctions are not erased but rather transcended in a higher wholeness. Up here, “this” and “that” are seen as symbions (interdependent organisms) in a larger ecosystem which both empowers and draws upon their cooperation.

Now for some application.

The reality of American life is and has always been persistently ambiguous. From the beginning there have been differences among us, and some of the most highly charged differences fall under the constructs of religion, race, and politics. We need to remind ourselves that these constructs are fictional categories and not objective realities. Being Black or White is one thing (in reality); what it means to be Black or White is quite another (in our minds).

Race relations in American history have been complicated because each side is telling stories that exclude the other. The same can be said of religion and politics as well.

Some of us are telling a story of division. According to this story different races, religions, and political parties cannot peacefully coexist, much less get along or work together. The ultimate resolution for them – called in some circles the End of the World or Final Judgment – will be a permanent separation of “this” from “that.”

No more grey forevermore, Amen.

The more open-minded and cautiously hopeful among us nevertheless complain that because so many of these others are telling stories of conflict and exclusion, it might be better for the rest of us to leave them behind. They observe how our current president and the Religious Right that supports him share a conviction that “winning the deal” or “converting the sinner” is the only way forward. Once these stalwart true believers lose cultural real estate and finally die out, we will be able to make real progress.

But that’s a story too, isn’t it?

What about this:

America is a national story about (1) racial diversity, religious freedom, and political dialogue; (2) around the central values of self-reliance, civic engagement, and enlightened community; (3) protecting the rights of all citizens to pursue happy, meaningful, and fulfilled lives.

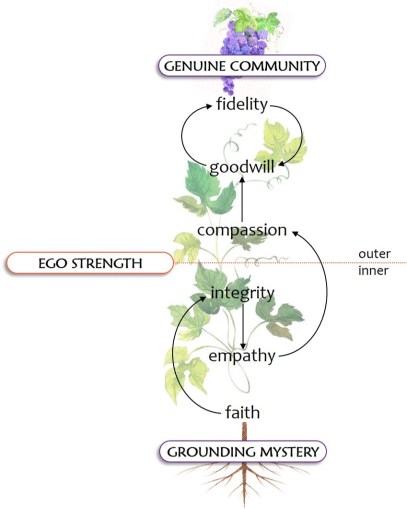

Is this story true? Well, what does it mean for a story to be true? According to constructivism, the truth of a story has to do with its power to shape consciousness, set a perspective, orient us in reality and inspire us to creatively engage the challenges we face with faith, hope, purpose, and solidarity. For most of our history true stories have brought us together in community. Indeed, they are the very origin of human culture.

The provisional answer, then, must be that an American story of upward resolution (unity) will be true to the degree in which we devote ourselves to its realization. Short of inspired engagement, a story merely spins in the air without ever getting traction in reality. It never has a chance of coming true.

Are there racial conflicts, religious bigotry, and political sectarianism in America? Yes, of course. But look more closely and you’ll find many, many more instances of interracial concord and friendship, a grounded and life-affirming spirituality, and individuals of different political persuasions talking with (rather than at) each other about ideals they hold in common.

If we give the media authority to tell our American story, we can expect to hear and see more about where the ambiguity is breaking downward into division. Why is that? Because the media depend on advertisers, advertisers need eyeballs on their ads, and stories of aggression, violence, and conflict get our attention. Cha-ching.

Strangely, but perhaps not surprisingly, if we hear the same story of division several times during a media cycle, our brain interprets it as if there were several different events – more frequent, more prevalent, and more indicative of what’s going on in the world.

There’s no denying that we need leaders today who genuinely believe in the greater good, who dedicate their lives to its service, and who tell a story that inspires the rest of us to reach higher. Complaining about and criticizing the leaders we have will only amplify what we don’t want.

The real work of resolving the persistent ambiguity of life is on each of us, every single day. Starting now, we can choose peace, wholeness, harmony, unity, and wellbeing.

The stories we tell create the world in which we live. America is worthy of better stories.