According to its etymology, religion refers to the process and cultural enterprise of putting together, linking back (Latin religare), or re-membering our wholeness as human beings. In reality, we never lost this centered integrity. And even now, despite our common – arguably universal – affliction of feeling off-center, dismembered, estranged, and alienated from our original nature, we are whole; not already, but still.

Nevertheless, this affliction of feeling alienated from what we essentially are – what is also known as suffering (dukkha in Pali, chatá in Hebrew, hamartia in ancient Greek) – is basic to the human condition.

While some errant traditions of religion reconceived it on the goal of delivering the afflicted personality out of the conditions of suffering, the longstanding mandate of what might be called “true religion” has always been to provide support, guidance, solidarity, and inspiration for the Human Journey through life.

Religion’s primary medium and technology for assisting in this Way is story, and a special kind of story known as myth. Over the long history of every human culture, mythology refers to the collection of myths that account for (i.e., provide a contextual understanding and explanation of) human suffering, as they also show the Way home to wholeness – the original meaning of salvation.

Whether the characters and events of myth actually exist or ever really happened is irrelevant to its truth, which instead speaks to the power of sacred story to wake us up and set us free.

The Way home to our wholeness is this process of waking up and realizing what we are.

In this post we will explore the matrix of archetypes, themes, motifs, and insights that generate the myths we live by. If one way to think about religion is as a mythology of sacred stories by which a community or culture orients itself in Reality, we can also classify religion thematically according to the coordinated timing of its stories with the progression threshold of human development in time.

Simply put, our progress in becoming more fully human not only benefits from but requires an anthology of myths linked together (religare) in a sequence across our lifespan, generated out of the matrix in which we live and move and have our being. The more conscious and intentional we are in putting our thoughts, beliefs, actions, and aims into accord with its principles, the healthier, happier, and more harmonious our life tends to be – because we are living from the center of our wholeness as a human being.

Before we take a closer look at the matrix of myth and its principles – those archetypes, themes, motifs, and insights that shape our human journey – it’s necessary to acknowledge another force field which can attract, or better, distract our focus of intention from what we essentially are.

This is the World, where we as self-conscious actors manage our personal identities in a shared quest for meaning and purpose on its social performance stage.

Importantly, ‘World’ is not a reference to what we sometimes call “the real world” (or Reality), but instead – quite literally, in its stead or as a construct of imagination (an imaginarium) that encloses and separates us from Reality – serves as the multi-stage theater to our personal quest for identity, meaning, and purpose.

The very concept of person, personal, and personality is itself derived from ancient theater, where it literally referred to the character mask through which (per) an actor would speak (sona) their lines in a play.

Needless to say, our personal quest for identity, meaning, and purpose takes a lot of time and energy. Without some deeper sense of what’s really going on – of what we earlier called our Human Journey to the realization of wholeness – the World’s myriad distractions can get us tangled up in things that aren’t even real.

This is why an intentional discipline of some kind, by which the guiding principles of mythology can be consciously accessed and appropriated, is so essential to our human wellbeing and fulfillment.

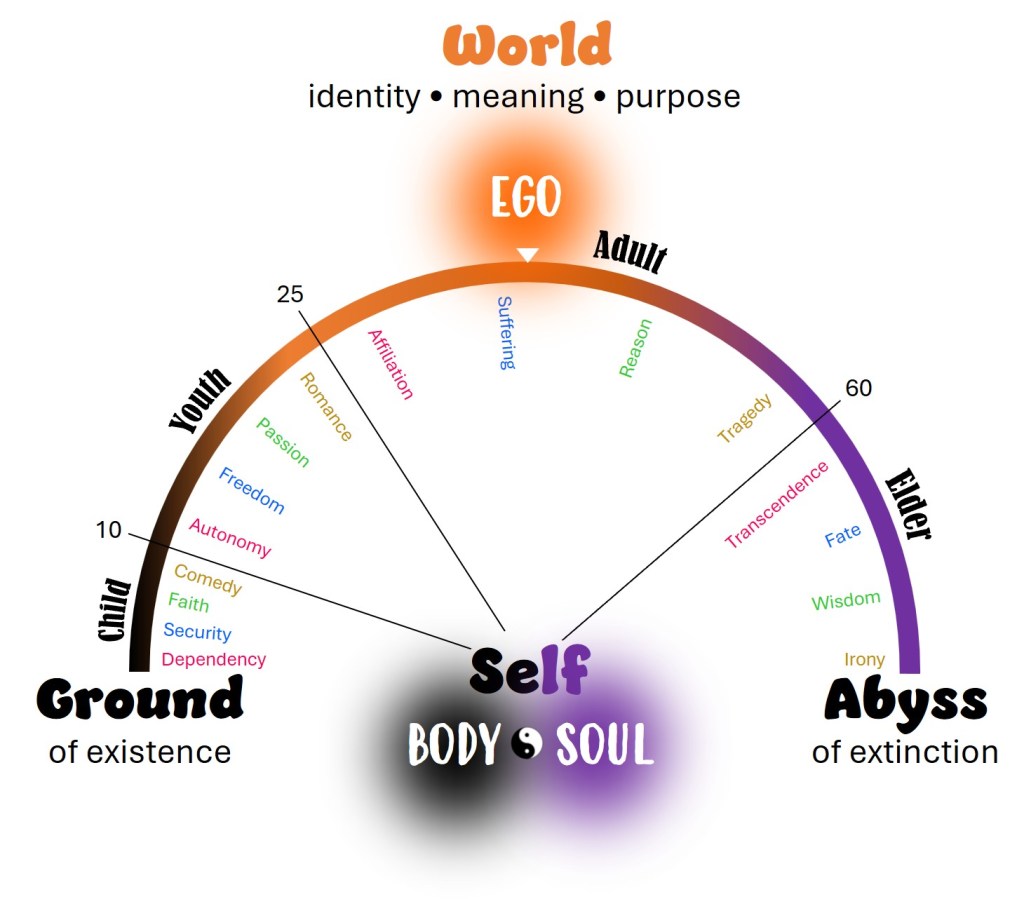

We won’t have time in this post to explore all twenty principles of the matrix in detail. It will be sufficient to gain an understanding of its organizing logic and thematic variations. What we see in the illustration above is the arc of a human lifespan, extending over time through a gradient of colors ranging from black (body-centered) to orange (ego-centered) to purple (soul-centered). Its continuum of consciousness (body-ego-soul) is further divided into four ages, represented in the mythic archetypes of the Child (birth to age 10), Youth (age 10 to 25), Adult (age 25 to 60), and Elder (age 60 to death).

In world mythology, a character’s age in life (Child, Youth, Adult, or Elder) is the clue to what possibilities of human nature are being represented and explored.

Each Age of Life is a “mything piece” of the Whole Story, and the logical structure of each piece plays out consistently across the entire lifespan. In the illustration, the structural elements are also color-coded to help us appreciate this consistency and how the mythology of all four mything pieces unfolds through their distinct “chapters.”

The way to read the elements is across the arc starting upward from the bottom-left with a group associated with the Child archetype. Thus in childhood we are in a state of dependency, oriented by our need for security, nurtured (hopefully) in an attitude of faith or trusting release, and find our most relevant truth in the literary genre of comedy – in the up-swing of “happily ever after.”

Childhood’s gift is an inner assurance that Reality is caring, responsive, and provident.

This parental Reality is depicted mythologically in early forms of theism as Father Sky (the “heavenly father” of early Christianity) and Mother Earth.

In Youth we are moving into a state of autonomy and oriented by a need for freedom. Our predominant attitude in this Age of Life is passion, as we develop strong and enduring feelings about ourselves, other people, and the World around us. The genre of story we find most compelling is romance, featuring the heroes and heroines who follow their hearts into brave adventures of defiance, discovery, conquest, and love.

The passions of youth galvanize the ideals and stereotypes through which we will continue to view the world.

As an Adult our journey takes us beyond adolescent ambitions and into webs of affiliation, where we begin to anchor our identity to the people, places, and things that make our life meaningful. Inevitably (just as the Buddha predicted) the impermanence of all these investments and our insistence on holding onto them leads to suffering.

We no longer find the conventional prescriptions effective or satisfying, but seek instead for the reason – a deeper meaning and higher purpose – in tragedy, which is the genre of story that addresses the unavoidable eventualities of bereavement, failure, hardship, and loss.

Finally, in late life as an Elder, the matrix of myth invites us to transcendence, to “go beyond” the givens of fate while learning to live more humbly and mindfully inside its limits. The insights that arise as we slow down and learn to behold the Eternal Now in the passage of time are seeds of wisdom, by which a more holistic understanding of life may be attained. This double-vision, between what is fading at the surface and what is shining in the depths, makes irony the genre of story that speaks most directly to our experience.

Dying is not itself the conundrum, but how to live life fully in the shadow of death.

What difference would it make if we were to intentionally put these “mything pieces” of our Human Journey into a single overarching narrative? Would we worry less? Would we spend less time looking for Something That we already have, Something That is still within us because we never really lost it?